Yesterday, while dissembling, I had what I might loosely describe as a “bugger” moment. Yale’s Enviroment360 web site (which I plugged on its introduction last June) currently features an interview with Robert Bindschadler, a NASA ice expert who is working on the Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers in West Antarctica. The “bugger” moment?

Yesterday, while dissembling, I had what I might loosely describe as a “bugger” moment. Yale’s Enviroment360 web site (which I plugged on its introduction last June) currently features an interview with Robert Bindschadler, a NASA ice expert who is working on the Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers in West Antarctica. The “bugger” moment?

e360: And in the theoretical case that Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers completely dump into the ocean – obviously it’s not going to happen in the near-future – what kind of sea level rise would they contribute to?

Bindschadler: That portion of West Antarctica, that third that flows northward primarily through those two glaciers, has the potential to raise sea level 1½ meters. That’s sort of an upper bound, a worst case. But the time scale is what really matters. Some say that we won’t see these ice shelves disappear in our lifetime – I’m not so sure. I think we might well.

e360: Are you kidding?

Bindschadler: No, no at all.

Bindschadler looks to be about my age. He reports that the ice shelf is melting from the underneath at a rate of about 50 metres per year at the grounding line. And then, a little later, just to make me spill my tea on the keyboard:

e360: I know that the IPCC was saying maybe 1 ½ feet or a half-meter of sea level rise in the 21st century. Is it your opinion that we could be looking at significantly larger sea level rise?

Bindschadler: Yeah, I think there’s sort of an unspoken consensus in my community that if you want to look at the very largest number in the IPCC report, they said 58 centimeters, so almost two feet by the end of the century. That’s way low, and it’s going to be well over a meter. We may see a meter by the middle of the century.

e360: Oh my gosh.

Bindschadler: And if this behavior that we’re seeing in Pine Island, and even Greenland continues – and we don’t see any reason why it wouldn’t continue – well, over a meter by the end of the century, I think is almost certain.

How notably prim the interviewer is. I think I might have managed something a little more Anglo Saxon. A “meter by the middle of the century” is a very long way above most people’s worst case (though not, perhaps, Hansen’s), but it makes our vulnerability to sea level rise much more of a near-term danger than a comfortable reading of AR4 might suggest. It’s a fascinating article — goes into more detail about the WA ice sheet and PIG (yes, that’s what they call it) than anything else I’ve seen in the last few years. Recommended, but not if you have beachfront property.

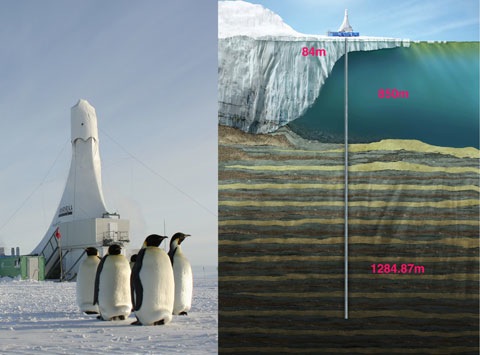

Meanwhile, a workshop being held at VUW in Wellington is looking at Andrill results, and finding that the WA ice sheet shows signs of repeated meltbacks over the last five million years [Stuff]:

Professor Tim Naish, director of Victoria University’s Antarctic Research Centre […] is co-science leader of the $30 million Andrill project on the ice, with Professor Ross Powell from Northern Illinois University in the United States.

“Antarctica’s ice sheets have grown and collapsed at least 40 times over the past five million years,” Prof Naish said.

“The story we are telling is around the history and behaviour of the ice sheet … as an analogue for the future,” he said.

Not good news, it seems. Expect a rush of papers covering Andrill work over the next few months.

[Johnny Cash]

The last time CO2 hit a sustained level of 400 ppm 15-20 million years ago global average temperatures were 3 – 6ºC warmer than now, and sea level was 25 to 40 m higher, according to research released last week. That’s bad news, because the target for current international negotiations to find a successor to Kyoto is 450 ppm. The finding also provides support for James Hansen’s view that 350 ppm is the maximum “safe level” for CO2 if we want to inhabit a planet with ice at both poles.

The last time CO2 hit a sustained level of 400 ppm 15-20 million years ago global average temperatures were 3 – 6ºC warmer than now, and sea level was 25 to 40 m higher, according to research released last week. That’s bad news, because the target for current international negotiations to find a successor to Kyoto is 450 ppm. The finding also provides support for James Hansen’s view that 350 ppm is the maximum “safe level” for CO2 if we want to inhabit a planet with ice at both poles.

The last time that atmospheric CO2 levels were as high as today, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) regularly retreated or collapsed, causing sea level rises of up to 7 metres according to the first analysis of the first

The last time that atmospheric CO2 levels were as high as today, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) regularly retreated or collapsed, causing sea level rises of up to 7 metres according to the first analysis of the first

The

The  Yesterday, while dissembling, I had what I might loosely describe as a “

Yesterday, while dissembling, I had what I might loosely describe as a “