This week climate minister Nick Smith and international negotiator Tim Groser start their 2020 emissions target roadshow, ostensibly taking the pulse of the nation on the question of what target New Zealand should commit to in the run-up to Copenhagen in December. Much of the argument will undoubtedly centre around the costs of taking action. The government has already signalled it won’t commit to targets likely to damage the economy, but there is a bigger question to consider — what emissions cuts does the world have to consider in order to avoid the worst effects of climate change, and how should New Zealand play its part? Any cost to the NZ economy is only a small part of that overall equation, and (arguably) not the most important. I want to examine what “the science†is telling us about a global goal and how we get there, and what that means for New Zealand. The leaflet produced to accompany the consultation process is pretty feeble in this respect, so I make no apologies for going into some detail here.

This week climate minister Nick Smith and international negotiator Tim Groser start their 2020 emissions target roadshow, ostensibly taking the pulse of the nation on the question of what target New Zealand should commit to in the run-up to Copenhagen in December. Much of the argument will undoubtedly centre around the costs of taking action. The government has already signalled it won’t commit to targets likely to damage the economy, but there is a bigger question to consider — what emissions cuts does the world have to consider in order to avoid the worst effects of climate change, and how should New Zealand play its part? Any cost to the NZ economy is only a small part of that overall equation, and (arguably) not the most important. I want to examine what “the science†is telling us about a global goal and how we get there, and what that means for New Zealand. The leaflet produced to accompany the consultation process is pretty feeble in this respect, so I make no apologies for going into some detail here.

The first question is the hardest to answer: what level of atmospheric greenhouse gases can we live with? In UN-speak, the international community is committed to avoiding “dangerous anthropogenic interference†with the climate, and this has come to mean a target of limiting warming to 2ºC above pre-industrial temperatures. However, there is no guarantee that 2ºC, even if it were achievable, would be “safeâ€. Consider this graph:

This comes from a paper by Ramanathan & Feng last year (On avoiding dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system: formidable challenges ahead, PNAS Sept 2008, here), and shows the likely equilibrium warming (ie the eventual warming, as the climate system catches up over the course of decades) expected to result from 2005 greenhouse gas levels, if the cooling caused by man-made pollution (aerosols, the Asian Brown Cloud, for instance) is ignored. The peak of the probability curve lies at 2.4ºC above pre-industrial temperatures. Forget the aerosols for a moment (I’ll come back to them), the main point is that we’re already well past our target. We can cut emissions all we want, but we’re just adding to the eventual warming over 2ºC. Look at the danger points in blue above the curve. The Arctic summer ice is most vulnerable, followed by the Himalayan and Tibetan glaciers, then Greenland and so on. The take home message? There are already enough greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to cause significant and damaging change to the global climate system, and the reason we’re not yet seeing the full effect is because our pollution of the atmosphere with aerosols is doing us a very big favour.

In the international negotiations under way for the successor to the Kyoto Protocol (I’ll call it K2), the 2 degree target has become associated with a 450 ppm CO2-equivalent “cap†to atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations. This is derived from the lowest set of greenhouse gas stabilisation scenarios considered by the IPCC (summarised in Table SPM6 of the AR4 synthesis report [PDF]), but in this context CO2-equivalent is not simply an expression of the total amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, but factors in the cooling effect of aerosols. This can be referred to as CO2e(total), but gets shortened (somewhat confusingly) to plain old CO2e, and in 2005 this was 375 ppm. In other words, CO2e(total) is roughly the same number as CO2 (no e), because aerosols and pollution cancel out current levels of methane, nitrous oxide and other minor gases. Here’s the table from the IPCC:

The scenario being considered when the government refers to a commitment to 450 ppm CO2e is the top line in the table. Look at the column second from the left: it gives the peak concentration of CO2 (not e) considered — 400 ppm. We’re currently in the high 380s and rising at 2 ppm per year. Then look at the date when emissions have to peak. The range is 2000 – 2015. In other words, global emissions have to start declining over the next six years. Even if by some miracle we manage to achieve that, we’re still committed to warming of up to 2.4ºC, and we’re also relying on the continued cooling effects of aerosols… If that sounds like a tough ask, it is. I don’t believe there’s any chance that the international community will get anywhere near to that sort of action — but it’s where the negotiations are starting. The table also provides the most commonly used starting point for the target debate — where we need to be in 2050. The scenario suggests that global reductions of 50% to 85% will be required. In practice, this seems to have become 50% by 2050 for global emissions — an assumption at the optimistic end of the spectrum — and is what our National-led government had as its pre-election policy for New Zealand emissions.

Getting to national targets from global ones is not easy, however. You can’t just ask everyone to cut by half, because developing countries — the biggest being China and India — point out quite correctly that the gases in the atmosphere causing the problem were not emitted by them. Current levels of CO2 have accumulated in the atmosphere as a result of fossil fuel burning in the developed world over the last 150 years, and only a tiny fraction of that has come from the less-developed countries. The argument’s simple. You got rich by emitting this stuff at no cost. If you want us to cut emissions, you need to give us room to grow. And so you arrive at the only game in town: contraction and convergence. In its purest form, this means setting a per capita emissions level for some point in the future, and then allowing countries to converge on that figure. Those with low emissions will be able to grow towards the new average, while the developed world will have to make cuts — and for the richest, they will have to be steep cuts. From this, we get to calls for developed nations to commit to cuts of 80% by 2050, and there are encouraging signs that the most powerful countries are ready to sign up to that. New Zealand, despite being tiny, is a part of that rich club, and has per capita emissions among the highest.

The question of 2020 targets flows on from consideration of emissions in 2050. If you’re going to get to 80% or thereabouts, you need to start cutting back soon. In the real politik of K2 negotiations, the developing world has been calling for the richest nations to commit to targets of around 40% by 2020 in order to show good faith, and to encourage important new emitters like China and India to take on some serious emissions commitments. The government’s overview leaflet provides a few examples, but omits the biggest — Britain’s commitment to cuts of 34% by 2020. All fall short — far short in most cases — of 40%.

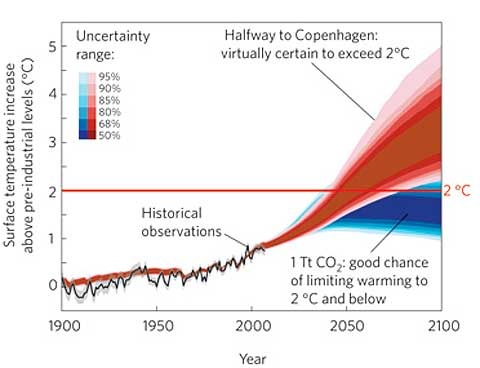

The cuts that are so far on offer also fall a long way short of achieving the 2ºC target the world has adopted. In this month’s NatureReports: Climate Change, Malte Meinshausen et al pull together all the commitments made to date, and plug them into a model to see what impact they’ll have.

As this figure from the paper shows, current commitments effectively guarantee a 2ºC rise by the middle of the century, and 3ºC or more by the end. The authors propose an alternative strategy, that of adopting a carbon budget — a cap on the total amount of carbon that can be emitted up to 2050. They propose a figure of one trillion tonnes of CO2, and their model shows that this would give a very good chance (75%) of meeting the 2ºC target. Unfortunately, though one trillion tonnes is certainly a big number, applying that to global emissions implies global cuts of 70% by 2050, and therefore significantly more than 80% by the developed world

OK, let’s pause a while in our thoughts about targets, and return to the really hard question — what level of atmospheric greenhouse gases must we hit if we’re to avoid the worst effects of warming. As we’ve seen, even the lowest cap being considered does not guarantee we can come in under 2ºC, and there are aspects of dangerous change that might happen at or before that point. There are also positive feedbacks not considered in the IPCC scenarios — things like an increase in methane from melting permafrost and sea floor methane hydrates — that could kick in. At the same time, we have to remember that the sort of action that will reduce emissions will also tend to clean up aerosols (by cutting coal burning, for instance), “unmasking” some warming. Should we therefore be aiming under the 450 ppm CO2e that’s on the table at the moment? The answer, according to James Hansen, is yes. Hansen’s 2008 paper, Target atmospheric CO2: where should humanity aim? [PDF] proposed 350 ppm CO2 (not e) as a “safe†upper limit — one that would maintain a planet with ice at both poles and a climate system at least similar to the one we have now. 350 ppm has since become an important number for people campaigning for action on climate change, and prompted Bill McKibben to set up 350.org as an organisation aiming to mobilise political thinking, to focus minds on something more ambitious than the cuts on the table in K2 negotiations. If politics is the art of the possible, then 350 ppm — which means going beyond 100% emissions cuts and actively removing carbon from the atmosphere — is probably too difficult, at least for the here and now. The fact that people are considering steeper targets does however carry an important message for policy makers here and overseas.

When deciding policy, it’s helpful to have some idea of the balance of risk associated with any decision. If the climate risks were perfectly symmetrical, that is to say that the risk of there being no problem to address (and that therefore anything done is a waste of time and money) is equivalent to the risk that the problem will be worse than expected, then it would make sense to steer a cautious middle course. But the risks aren’t symmetrical. The risk that the problem will go away of its own accord is essentially zero. There is a real possibility that the world will decide a cautious middle course (heading for something over 450 ppm CO2e) and then discover that it’s really urgent that we head for 350 ppm at a wartime pace — perhaps because positive feedbacks are becoming all too obvious. At that point, having national policy in place that can respond quickly — or having aggressive targets in the first place — makes a lot of sense. This is the real strategic context for decision making on NZ’s emissions targets. It requires us to make an informed risk assessment — one based in the facts, not wishful thinking or economic forecasting — and take worst cases into account.

When you apply that logic to the National-led government’s “50 by 50†target it is obvious that it needs revision. At the very least it fails to match the long term targets of the club we want to part of — the developed world. As the most recent NZIER/Infometrics report noted, that’s a tent we very much want to be inside so that out exporters can continue to trade without carbon tariffs. At the very least, the government should adopt an 80% by 2050 target, and make contingency plans for that increasing to 90%. Better still would be to adopt the previous government’s goal of carbon neutrality by the same date (preferably earlier).

With steeper long term cuts in mind, the focus for 2020 targets becomes clearer. This graph is taken from an earlier post about Solid Energy’s suggestion that a massive investment in forestry could be used to create a national offset scheme:

The yellow line points to 80% by 2050, and (approximately) passes through 25% in 2020. Ignore the detail above the line. 25% looks to me to be the minimum credible target that New Zealand should adopt. It is a little more than the EU and a lot more than the US, but puts us on a credible emissions pathway. On the other hand, there is merit in aiming for a tougher target (350.org.nz and Greenpeace, for example, advocate 40% by 2020). This would put us in line with the demands of developing countries and the small island states in the Pacific, and could help us to play a bigger part in brokering a Copenhagen deal. Whatever the final target, of course, it is necessary to design credible policy that can get us there. Should we have different targets for different sectors, as the Greens have suggested? That’s an open question as far as I am concerned. I haven’t seen enough detail of what might be involved, and remain sceptical of moves to exempt or delay agriculture reducing its emissions. If there were to be a split target that gave agriculture (50% of our emissions, remember) a softer ride in the short term, then that would have to be balanced by steeper cuts in other sectors, or a more rapid expansion of forests as carbon sinks. There are therefore equity issues to be addressed, as well as questions relating to the sorts of policy levers a centre-right government is prepared to pull.

The government’s information leaflet for the consultation process asks if NZ should consider conditional targets. The EU, for instance, has promised a 20% cut by 2020 whatever the outcome in Copenhagen, but will move to 30% if there’s agreement. Having said that I think the minimum credible target for NZ is 25%, that suggests that we could commit to, say, 40% in the event of a tough global deal, falling back to 25% in the event of failure. From our negotiator’s point of view, that ought to give our place at the table a little more weight and our exporters a place inside the tariff tent if a deal can’t be done.

I will be attending the consultation meeting in Christchurch on Wednesday. If I have the opportunity, I will try and articulate the above view, albeit somewhat more succinctly… 😉 But I am reminded of an old, old joke. With apologies to those of Irish heritage: A British couple are driving through the Irish countryside, trying to find the way to their hotel in Cork. They stop by a farmer on his tractor, and ask for directions. The farmer scratches his head and replies “Ah now sir, if I was you, I wouldn’t start from hereâ€. My feelings precisely.

And for the record: whatever the politics and practicalities of setting NZ’s targets, I endorse and support 350 ppm as a global target for atmospheric CO2. It strikes me as a difficult goal, but a prudent one.

I went to the talk at Te Papa last night. Some of Nick Smith’s points that I remember him saying are:

– If we were to set a Target of 40%, that would mean having to reduce all transport, electricity and stationary emissions to zero by 2020, assuming that agriculture would stay the same. This would mean everyone at Tiwai Pt would lose their jobs, as well as lots of other industries.

– It is hard to reduce agriculture emissions so we should consider a lower target because of this. During all of the questions he had a slide up showing a bar graph with the sectoral make up of New Zealand’s emissions, next to bar showing 1990 levels, -20%, and -40%.

In each of these arguments Nick Smith is conflating a domestic target and an overall emissions target, including international trading. As I understand it, developed countries are expected to set targets above what they can achieve domestically.

Developed countries setting tough targets will, via trading, provide money for developing countries to reduce emissions while continuing development. This is an equity issue, as these countries have not emitted as much historically as the developed countries.

I am concerned that Nick Smith, by not distinguishing between a domestic and a overall target, including trading, that he is making a 25%-40% target look much more difficult than it actually is.

Secondly, I don’t think his point about agriculture is relevant to the target. If he Nick Smith is correct and agriculture emission reduction is expensive, then credits will be bought internationally. If he is wrong the emissions reductions will be bought locally. I don’t see how this should affect the overall target, it will affect the domestic target however.

Thirdly, the previous government’s ETS already planned for transport and electricity sectors to have 100% of their emissions covered. In other words, that scenario is already close to the “horror” situation that Nick Smith outlined in the first point above. Once you get rid of the domestic/overall target confusion, suddenly it looks very achievable, it’s a few cents per litre and a few cents per kwh.

If you agree with this, I would appreciate if you could mention it to the Minister at the next meeting. I’ll have a go at writing him a letter.

Cheers,

Greg.

Thanks for the insight, Greg. Yes, it does sound as though he’s ignoring the offset and trade side of the equation. Sounds similar to the arguments in the Greenhouse Policy Coalition’s new economic report (Scoop, full report not available yet, as far as I can tell).

And tonight in Auckland could be a good night: Greenpeace are rolling out the stars (and Jim Salinger’s rubbing shoulders with Lucy Lawless, lucky man… 😉 )

I was also at Te Papa last night. I agree Nick SMith was trying to make things appear more difficult than it needs to be.

By saying that expected 2020 agriculture emissions by 2020 would make up all of our allowed emissions (under a 40% reduction) misses a number of points.

It assumes agriculture cannot be reduced at all and will continue to increase at the same rate.

He also neglected to consider carbon sinks (forestation)

He spoke of job losses but no mention of any positive outcomes of creating a more sustainable New Zealand.

He made the point that our emissions from energy generation almost all come from peak load (i.e. needing to use Huntly etc during peak times). This proves that it would be possible to remove virtually all emissions from energy generation by reducing peak load (truly smart meters would be a good start), improving overall efficiency and only investing in renewable energy sources.

Transport is another area that could be easily cut. I saw report today which showed only 5% of Aucklanders use public transport to commute. Unfortunately the Govt. is not willing to address this by investing in rail over roads.

Unfortunately a 40% target is only achievable if the government is willing to change key policies which they are clearly not going to budge on. After last night I don’t hold much hope of any sort of responsible target being set.

Another interesting statement: a commitment to the electrification of Auckland’s Rail Network. I couldn’t remember seeing that elsewhere, and I snidely wondered before researching the facts, did he tell John Key about that?

However it is very good to see a commitment from the government to the 2°C warming level, however disheartening the table they produce which seems to be all about justifying returning to 1990 levels at best, not the 40% by 2020 cut called for by scientists.

I still look forward to seeing a full write-up on the Carbon Farming Couple, and have just forwarded information to the Hon. Smith, and committed to traveling to the Hamilton meeting next week to prompt the minister about it. My back of the envelope calculations indicate that NZ could become a net exporter of carbon credits by 2020 on dairy farm agriculture alone. Let alone the Treemasters (was it?) who were talking about transforming vast areas of NZ scrubland to forest.

Kieran, I don’t think it’s fair to say that Nick Smith did not consider forestation/carbon sinks – he spent a lot of time talking about that. Just not additional forestation.

Sam, FYI Bryan’s article will be posted here in full tomorrow. I look forward to discussing the implications…

[Oops: I see that’s not Bryan’s column… but he will cover the subject for us soon.]

Yes, I’m writing a column for the Waikato Times on carbon farming, with the assistance of a local soil scientist involved in a move to set up a NZ carbon farming association. I can’t publish it here until it has appeared in the Times, but my reading certainly confirms, Sam, that there is a surprising potential even in NZ for significant measureable carbon capture in just the course of regular agriculture provided some of our practices are altered.

Sigh… did have tickets booked etc, but fell sick and couldn’t make it. Good luck putting across the potential to the minister and farming community tonight Bryan …

I agree that there are lots of projects that need to be started now, to work on reducing NZ’s domestic emissions. We should probably set a 2020 target for domestic emissions, including a breakdown for each sectors.

I also think that NZ should set an overall target which is above these domestic targets. This target would be achieved by first making the domestic reductions, then for the remaining amount, buying credits, and the government could initiate it’s own projects, for example cooperating with PNG/Indonesia to reduce tropical defforestation. The reductions from these projects can then be offset from our domestic emissions. This would be similar to Norway’s cooperation with Brazil.

Given that Nick Smith supports international carbon trading, emissions reductions in NZ are not important in estimating the cost of reaching an overall target. The important number to estimate is what the international carbon price will be in 2020 – nobody is very certain about that yet – but everyone is in the same boat there.

So I am worried that by mixing up domestic and overall targets, and talking only about domestic reductions, the issue gets confused, making it harder to set a responsible overall target.

So what you are saying is:

Set a target we cant meet.

Pay other people to buy carbon credits.

Sounds like a genius idea. Are you a member of the Green party?

R2 RU suggesting that we should aim to do all of our emissions reductions locally?

I think that cooperating with developing countries to help them reduce emissions is a sensible idea, especially given the historical inequality of the situation.

This seems to also be a position that all of the other countries announcing targets agree with – are you suggesting that they have all got it wrong – why should our target be any different from theirs?

Nicholas Stern’s recent book talks about this in more detail if you are interested. Bryan reviewed it recently. If you disagree – fine – I’m always open to reading clearly written rebuttal. I’m not so keen on snarky comments however.

In fact R2 this is not that stupid an idea. Set targets which are in line with what the scientists say, because you’re a rationalist and happen to listen to scientific advice, and if we can’t meet them domestically then pay other people to do it for us. The government can just allocate credits based on what they are currently using minus the 63% or whatever it is and let the industries involved figure out how they are going to pay for the shortfall – the impact of running their business – themselves.

The other people being paid are providing a service, that is sinking carbon for carbon intensive industries. Far from being a Green solution, it is a market-based solution. It includes possibilities which a staunch Green would never support, like paying someone to go grow some Radiata forests.

However I think what is far more likely is that NZ will lead the way on controlling agricultural emissions and turning agriculture into carbon positive operations. Capital investment will be towards power sources which do not require expensive carbon credits to be purchased. Companies which find they are not getting a good price on the international markets and can purchase land to use for dedicated carbon farming will do so as the market dictates.

This is not a “Green” solution in the traditional sense at all. It contains too many instances of the word “market” for that. Your quip fails to meet the grade.

For the record I am not a Green, a Blue, or a Red. I support a policy based on my understanding of its merits.

R2 I challenge you to do the same, drop the inane one-liners, describe in detail your position. I may not share you views, but I am willing to discuss them.

(Samv – maybe one day I’ll figure out which reply button I’m supposed to click on, but I wouldn’t hold your breath…)

My position,

The reason we need to set a target is because of the UNFCCC 6 month rule (that we have already broken). We need to set a target as a first step in the negotiating process. We need to negotiate the lowest commitment period 2 (CP2) target we can.

When signing Kyoto we agreed to a 0% target. Aussie agreed to a +8% target. Regardless of if we meet the target or not, the cost of not negotiating a +8% target is about $750 million to the nation.

For the next commitment period we need to negotiate as favorable target as possible. We had 63 odd million tonnes of emissions in 1990. For every 1% extra we negotiate we get another 3.15 million units for CP2 (if it si 5 years). If AAU’s trade at $40 NZ dollars next CP, thats $126 million for every 1%.

There is no good reason to negotiate a low target. We are small. 0.2% of global emissions. The US, China and Russia are not going to care what we propose. We can not influence them.

CDM’s are a form of foreign aid. The most efficient form of aid is the simplest. If we want to help third world nations develop we can give them conditional foreign aid. We do not need CDM’s.

Setting a target we can not meet will result in net cash outflows from New Zealand. It will result in less money for the Govt to spend on unemployed and dependent people in NZ. I don’t know why you think this is a good thing. You mention that the overall pool of units will be lower. We are only 0.2%, we will not make a difference.

My position: Good negotiators will set as easier target as possible.

My last comment is a reply to Kieren’s post.

If only this government would take the necessity to cut carbon emissions as seriously as they take cuts to welfare, education, and health we could have 10% reductions this year!

Hmm, strange, there is no consultation in Horowhenua. Guess those people have to travel to New Plymouth.

(replying to an irrelevant comment to make up for Greg’s mistake above – on the principle that two wrongs make a right)

Thanks for the article Gareth. Clears up the CO2-CO2e-aerosols question well.

Hi Gareth – thanks for the round up. I’ll listen for your succinct summary tomorrow night as well.

btw my forebears are from Cork (and not too long ago either) – I find a certain wisdom in how the farmer answered the question.

Greg mentions Nicholas Stern’s book in his reply to R2’s rather sneering comment. I add a little detail for those who don’t have access to the book . His discussion of trading schemes emphasises that international trade across regions is of great importance “in the sense that private-financing flows from carbon markets will bring some developing countries into a global deal.â€

But before moving to develop this he comments on trading between rich nations, where a key sentence for the purposes of this coment thread would seem to be: “A region that has ambitious targets would understandably be reluctant to agree to trade with an area with weak targets, since such collaboration would water down global ambition.â€

On the crucial matter of trading between developed and developing countries he sees the necesity of two steps. The first is one-sided trading – meaning that an enterprise in a developing country can get credits for reducing emissions relative to a benchmark, but is not penalised for emissions above some level. The current Clean Development Mechanism has established the principle and started to build significant interest in low-carbon options in the developing world, with sizeable funds now beginning to flow. However the restriction of CDM to particular enterprises is too cumbersome for large scale one-sided trading, and Stern thinks a different structure needs to be developed which carries the CDM concept into larger schemes on say a city or province level.

But by 2020 he considers we should aim to have commenced the second step of integration of developing countries into world carbon markets, which means targets and an integrated two-sided trading scheme for all countries.

Thanks for details Bryan.

One other interesting point Stern makes is at odds with what most people write about contraction and convergence, including Gareth’s post above.

First some background:

– A large amount of the CO2 effectively stays in the atmosphere forever. [1]

– So we’ve effectively got a fixed amount of CO2 we can emit until the atmosphere is “full”. [2]

So imagine this fixed amount of CO2 being a pie, and countries being pie a group of hungry people, the contraction and convergence principle contends that an outcome is equitable, as long as the everybody’s last few slices are the same size.

In this example it seems obvious that counting the total amount of pie eaten by each person is a more sensible way to determine the equity.

Based on this Stern argues, that by 2050, developed countries overall targets should be close to zero carbon. Remember he is not suggesting that domestic emissions will be zero, rather that they will reduce and offset.

(Bryan – I lent my copy of the book to someone else, read it a while back, and am writing this from memory, so please chime in if I’ve mixed something up)

In an ideal world, we could just get on and solve this problem without trading/offsetting. But I don’t think that there can be a global agreement without trading/offsetting, we need the developing countries on board, without them there is no solution.

We also must take into account that politics in developed countries is easy compared to that developing – look at India’s attempts to remove their petrols subsidies, there were riots, they government had to cave. Trading and offsetting is a carrot, that can bring these countries on board – and it’s equitable – so we should anyway.

However surveys in New Zealand show that many are deeply sceptical about trading and offsetting[3]. I think climate-savvy citizens need to step up, and do a better job explaining this to our peers, especially given that Nick Smith isn’t going to be doing it for us.

I am still worried, that much of the discussion around NZ’s 2020 target is being diverted into discussing only our domestic targets, and therefore bypassing the core issues of a global deal, and international equity and the use of offsetting and trading. I think these issues are more important when deciding on a 2020 target.

[1] From memory something like 10,000 to 100,000 years. Yes it cycles through the biosphere and oceans, but these processes don’t actively change the global concentration on a short timescale.

[2] Enough to reach a 2C temperature target.

[3] The AA survey. Did anyone else notice that what they didn’t say, was that when you added up their numbers, a majority of the people surveyed were willing pay more than the forecast cost of the last government’s ETS.

For the atmospheric lifetime of CO2 — an exact description is complex, but a lot does hang around for a long time (how’s that for precision 😉 ).

For NZ, the most pressing current need is not for any particular target, or ETS structure, it’s for regulatory certainty. I had a long chat last night with someone who’s been working on forest carbon projects around the world (he might do a guest post for us soon), and if the government would just commit to a course of action instead of delaying, then there are a lot of good forest projects that could get under way very quickly. We had, in the PFSI and the forestry bits of the ETS a world-leading set of structures.

As I’ve said before: addressing NZs emissions is not just about costs, it’s also about opportunities. More on that, no doubt, in due course.

Beyond K2, we ought also to begin to think about how we organise reducing the carbon in the atmosphere. 350 ppm as a target might seem to be an outlier/a bit extreme at the moment, but I think it’s more or less inevitable that the world will have to head that way — if only to stop ocean acidification.

I agree that we need to get on with the job – keep the good articles rolling.

“Everyone at Tiwai Pt loosing their jobs” gets aired out every so often.

Someone did an analysis a while ago (posted on norightturn, I think) about what Tiwai Pt actually brings into the country, and concluded we’d probably be better off telling them to take a hike and re-jigging the national grid to use the electricity freed up. They get ALL the power from Manapouri, bring raw materials directly in by ship, send the processed metal directly back overseas (any added value going back to the parent company) and employ just enough locals to keep running.

Sorry for the OT post, but for future reference anyone who makes threats about closing Tiwai Pt is either uninformed or being disingenuous…

IIRC, it was an article in North & South…

Replying to R2 at #12 (seem to have run out of indents for the replies… I may need to tweak something somewhere):

There are very good reasons for setting a low target, and good negotiators will recognise that more than the narrowest of national interests has to be taken into account.

Some of those good reasons: NZ aspires to be part of the developed world, and that is inching towards an acceptance of 80% cuts by 2050. To be “inside the tent” in trading terms, we need to at least match that sort of commitment, and this post demonstrates, 25% by 2020 is the minimum credible cut on the pathway to 80%. Tourism is a huge chunk of our economy, and image is incredibly important. If one of the highest per capita emitters in the world isn’t seen to be pulling its weight, that business will suffer. Delaying action increases the costs of cuts when they are finally imposed (gentle change is cheaper than abrupt change – economically and climatically). That’s enough for me, but there is an additional — and for some, the most powerful — argument. It is simply the right thing to do, morally and ethically. Climate change threatens the destruction of our civilisation, and I do not want to sit idly by and watch it happen.

Also replying to R2 at #12

“We are only 0.2%”

Does that mean that we are 0.2% responsible? (Actually more if you count cummulitive rather than annual emissions)

Do you advocate completely ignoring that responsibility? If NZ ignores that responsibility, we make it 0.2% harder for the world to come up with a deal between developed and developing nations. No deal, no solution.

“I don’t know why you think this is a good thing.”

Are you really trying to argue: Why be responsible? – It just costs money – There are no benefits.

Responding to Gareth and Greg, good reasons for setting a low target.

“NZ aspires to be part of the developed world, and that is inching towards an acceptance of 80% cuts by 2050. To be “inside the tent†in trading terms, we need to at least match that sort of commitment”

But USA’s target is 0% of 1990, Canada’s +3% and Aussies are targeting 5% below 2000 levels (conditions are in their UNFCCC submission, impossible to meet). Russia is saying +30% from current levels for K2. So it appears the only ones in the tent are the EU, who have committed to 20%, with 30% conditional, so they are not really in the 40% tent either.

So it seems the only countries in the 40% target tent for developed countries are the developing countries. Hardly a developed country tent Gareth!

“If one of the highest per capita emitters in the world isn’t seen to be pulling its weight, that business will suffer”

We are one of the highest per capita producers of GHG’s. Not consumers. 50% of our emissions are used creating exports. We have low electricity emissions, high transport emissions. Other economies like the UK can have service based economies, but someone has to produce their goods.

They have a higher per capita consumption of GHG’s than us.

Consumption is more important, if businesses produce less then competitors will fill the supply gap and global emissions will not change. If individuals demand/consume less then businesses will produce less. If consumers demand low carbon footprint products that will have an effect too.

Greg, yes I really do think there are no benefits to a 40% target. NZ cutting 40% emissions wont have an effect on the climate. It wont have an effect on USA, Canada, China and Russia’s obligations. It will have a bad effect on our economy.

I guess that is what is driving our difference in opinion.

So to summarise your position: being responsible just costs money, there are no benefits, and since everyone else is being irresponsible, we should be too.

Meanwhile other countries, even China, continue to invest in methane digestors, nitrogen inhibitors, and reforestation projects. We’ve got a lot to lose if we’re shown to be a laggard.

“A total of 1,200 counties across the country are utilizing fertilizers according to the results of local soil tests to reduce emissions of nitrogen oxide—a less common but more potent global warming pollutant.”

“China has a target to increase forest area coverage to 20 percent by 2010 and has committed $9 billion annually toward this effort.”

http://greenleapforward.com/2009/06/04/chinas-climate-progress-by-the-numbers/

The “tent” to which I refer is 80% by 2050. You won’t find me disagreeing with the inadequacy of the various 2020 targets, but we need to share a common long term goal.

The costs of action are routinely overstated, but we hear little of the opportunities.

The fact is that we cannot afford to do too little. If we do too much we may lose a little wealth, but we will have saved ourselves and future generations. If that’s the choice, I so choose.

The conversation was about 2020 targets.

I am arguing it is a false choice you present. “If we do too much … we will have saved ourselves and future generations”

I don’t think anything New Zealand can do with our paltry 0.2% of emissions will have an effect on GHG levels by ourselves. I also do not think we can have an effect indirectly by influencing others. And I think given our national circumstances we will be forgiven for not cutting 40% (high renewables, exporting nation).

So it becomes a Nash’s game theory decision.

1.We cut 40%, ROW cut 40% = Low Emissions, NZ Wealth cost

2.We cut 5% BAU, ROW cut 40% = Low Emissions, Low NZ wealth cost

3.We cut 40%, ROW cuts 5% below BAU = High Emissions, NZ Wealth cost

4. We cut 5% BAU, ROW cuts 5% BAU, High emissions, Low NZ wealth cost.

The result is: regardless of what the rest of the world does, NZ is better off setting a soft target.

R2 Your reasoning displays no sense of the seriousness of the threat of climate change. We have obligations in the battle against global warming which we should be looking to shoulder, not avoid. Your 0.2% argument is specious when set against the morality involved.

My post discussed how 2050 targets set the context for 2020…

Your game theory matrix ignores the cost of inaction. You assume we will be “forgiven” not doing enough. I would suggest this is optimistic nonsense. The world does not owe NZ a living, and our competitors in export markets will not be slow to exploit any perceived failings. Note the speed with which the UK diary industry tried to use a food miles argument against NZ butter.

Doing as little as possible only makes sense in a very narrow context. The world ain’t narrow.

You got number 2 wrong. It should read:

We cut 5% BAU, ROW cut 40% = Low emissions, NZ economy collapses after ROW imposes punitive tariffs on our agriculture.

As Gareth says, you can’t just ignore the fact that the ROW is going to cut emissions, and the way this will happen is by putting a price on carbon. If we do not internalize that cost in NZ (through ETS or whatever), then the ROW will make sure that we pay the cost externally.

CTG, what real world evidence do you have that tariffs will be placed on NZ agriculture if NZ does not adopt an aggressive target (10+% of 1990)?

R2, have you read any of the articles on Copenhagen? The world is moving towards real tariffs on carbon very soon. The only way that emissions cuts are going to happen is by applying some sort of tariff on carbon. My point is, if we do not put a sufficiently high tariff on the carbon we produce ourselves, then the rest of the world will be more than happy to do it for us.

Say, for example, that the agriculture sector gets a free ride until 2015 or whatever they want. If the EU starts imposing carbon taxes on agriculture in the next year or two, then NZ agriculture would obviously be at an advantage, so you can expect the EU to put a tariff onto NZ imports in order to compensate.

Pretending that the rest of the world will ignore us because we only produce a tiny amount of the world’s emissions is pure head-in-the-sand stuff.

The shortfall in robust discussion around anthropogenic CC healing is in choosing which path and over what time frame to get us to a negotiated safe climate. While that would warrant some defining of what is safe and ‘who bears the burden’ in the interim, it is patently obvious that neither the current minister or the previous have paid ANY attention to Aubrey Meyer’s Contraction and Convergence [C&C]as the framework to address time, risk or the social dividend/costs.

This is clearly EVIDENT in the aversion of both MFE or MED to include C&C in ANY discussion documents to date.

Christchurch’s 2020 consultation was the first time ANY Minister of the Crown mentioned C&C’s merits despite its history in the international debate and its international standing.

I am not convinced Nick Smith gets it. As long as he (and presumably the Blue/Greens) put’s environment subservient to economy and tells the scary stories predicting high prices for electricity and fuels, he is doing nothing more than ‘canvassing’ his 2011 [re]election.

I gave him Song Li [World Bank]and Prof Mackey’s [ANU] paper a few days after it was published that more than adequately describes in lay terms the importance of commodifying carbon costs and harms into a unitary property rights based solution.

Now that Smith is Minister Responsible for Climate Change (an odd moniker if ever i saw one) one would expect better ‘policy options’ than the feeble discussion documents handed out thus far. These are IMHO purposely designed to do nothing other than look like they do something.

So far, all I can see from the consultation thus far is death by a thousand cuts.

Replying to R2 at #34

“CTG, what real world evidence do you have that tariffs will be placed on NZ agriculture if NZ does not adopt an aggressive target (10+% of 1990)?”

The ACES bill recently passed in the US congress, has a 17% 2020 target, and requires by law, border adjustment taxes starting in 2020, for imports from countries that don’t play ball.

The US and Europe both have powerful farming lobby. It would be risky for NZ to give these groups a justification for their protectionist interests.

CTG: “R2, have you read any of the articles on Copenhagen?”

Lol, yes I have read the articles. The difference is I have also read the texts.

Read article 3.5 of convention here:

http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf

And 130.b, 132, preamble x.1 to 134, 134 alternative 3 a, and 134.1 of the revised negot text here:

http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2009/awglca6/eng/inf01.pdf

The is a strong message in this section that for certain sectors, including agriculture, mitigation should be cooperative, and not include trade protections.

And Greg: I have read the tariff parts of the Malarkey-Taxman bill, I suggest you do the same, Sec 765-767.

http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=111_cong_bills&docid=f:h2454rh.txt.pdf

Not before 2025. The purpose statement of the section states that Tariffs be to equalise costs of compliance, the bill does not include agriculture so need to worry.

And anyway, the bill requires countries that are smaller than 0.5% of world emissions to be left out.

The target is 17% reduction for covered entities of 2005 emissions. Ag is not in, so there is no absolute target in the bill. Obama’s envoy has announced a target, but it is not the same as the W-M target.

CTG: What signals do you have the EU is about to put taxes on agriculture? The common agricultural policy is increasing subsidies, not implementing emissions charges. Like greg says, the EU and US have powerful farm lobbies. They got a great deal in W-M. What makes you think they will bring in agricultural taxes anytime soon? If they did why not wait and follow rather than lead?

I seriously suggest you both read section III.D in the negot text. That is where Copenhagen is at at the moment anyway. Anticipating some change is not based in the real world at the moment.

So I ask you both again;

What real world evidence do you have that tariffs will be placed on NZ agriculture if NZ does not adopt an aggressive target (10+% of 1990)? (and dont refer to all the news articles)

Thanks for the corrected figures.

It’s not impossible for the EU/US farm lobbies to argue for exemptions at home, and yet at the same time use climate change concerns to put up barriers. They could do this by comparing total emissions reductions as opposed to a sectoral comparison. Probably not an equitable line of argument, however as a small country, and given weak international law, we have to consider these risks.

Note, there are risks even if they are not written into the current negotiating text. Why would you expect them to be – the real world isn’t that simple.

I haven’t seen a clear strategy from the government, yet I see other countries making changes, both in their private companies and governments. I think it is entirely possible that NZ will be out-paced by other developed countries, exposing us to tariff risks.

“Malarkey-Taxman bill” – no comment needed.