I get emails from several Oxfords, but this week’s best came from the nearest and contained a link to “a lecture you’ll find worth looking at — coffee/keyboard interface warning.” The warning was heeded and needed. The lecture, by Dmitry Orlov, given to the Long Now Foundation in San Francisco on Feb 13 as a part of Long Now’s Seminars About Long Term Thinking, is titled Social Collapse Best Practices [Long Now report here, full text at ClubOrlov]. According to Orlov, who had direct experience of social collapse in Russia after the demise of the communist system (his thesis is that the US is moving rapidly towards closing its “collapse gap” with Russia), four things are important during a collapse — food, shelter, transportation and security. But especially security:

I get emails from several Oxfords, but this week’s best came from the nearest and contained a link to “a lecture you’ll find worth looking at — coffee/keyboard interface warning.” The warning was heeded and needed. The lecture, by Dmitry Orlov, given to the Long Now Foundation in San Francisco on Feb 13 as a part of Long Now’s Seminars About Long Term Thinking, is titled Social Collapse Best Practices [Long Now report here, full text at ClubOrlov]. According to Orlov, who had direct experience of social collapse in Russia after the demise of the communist system (his thesis is that the US is moving rapidly towards closing its “collapse gap” with Russia), four things are important during a collapse — food, shelter, transportation and security. But especially security:

Tag: Russia

Santa’s blues

What’s a Christmas icon to do, when all the ice at the North Pole disappears in summer? This startling question is posed by the latest flush of media attention to events in the Arctic. First there was a National Geographic story on June 20th speculating that the North Pole would be ice free this summer (note: this is nothing to do with record minima, just do with ice around the pole itself). This was picked up by CNN, who went to Mark Serreze of the NSIDC in Boulder, Colorado for comment:

What’s a Christmas icon to do, when all the ice at the North Pole disappears in summer? This startling question is posed by the latest flush of media attention to events in the Arctic. First there was a National Geographic story on June 20th speculating that the North Pole would be ice free this summer (note: this is nothing to do with record minima, just do with ice around the pole itself). This was picked up by CNN, who went to Mark Serreze of the NSIDC in Boulder, Colorado for comment:

“We kind of have an informal betting pool going around in our center and that betting pool is ‘does the North Pole melt out this summer?’ and it may well,” said the center’s senior research scientist, Mark Serreze. It’s a 50-50 bet that the thin Arctic sea ice, which was frozen in autumn, will completely melt away at the geographic North Pole, Serreze said.

And then everything went quiet, until The Independent in Britain (referred to as The Indescribablyoverhyped on climate matters by Stoat) picked up the story and ran with it under the headline – Exclusive: no ice at the North Pole:

It seems unthinkable, but for the first time in human history, ice is on course to disappear entirely from the North Pole this year.

They seem to be having problems with their choice of tense, and quite how they can justify the “exclusive” tag escapes me… The Drudge Report noticed, and then everyone in the world had to have a go [Telegraph, AP(*)]. Andy Revkin at DotEarth covers it well, and RealClimate chips in with its own analysis. It won’t be long before the usual denialist sites will be spluttering with indignation, despite the fact that the North Pole has a very good chance of being open ocean this summer – even if a new record minimum is not set.

None of this has any relevance to the odds of my winning my various sea-ice bets, but it does give me a chance to post a few interesting Arctic-related links from the last week… As part of its beat-up, The Independent went to Peter Wadhams, professor of ocean physics at Cambridge University, for his impressions on the changes in the Arctic, and the BBC’s been carrying a blog from Liz Kalaugher aboard a Canadian icebreaker that over-wintered near Banks Island. Interesting stuff – note Liz’s comments about the weather. Meanwhile, across the melting ice, the Russian defence establishment is beginning to get worried about the impact of melting permafrost.

(*) The AP story uncovers this truly remarkable and hitherto unnoticed fact: “That pushed the older thicker sea ice that had been over the North Pole south toward Greenland and eventually out of the Arctic, Serreze said. That left just a thin one-year layer of ice that previously covered part of Siberia.” So that ice has somehow left the land and started floating towards the Pole. Be afraid, be very afraid…

It’s the end of the world as we know it (and I don’t feel fine)

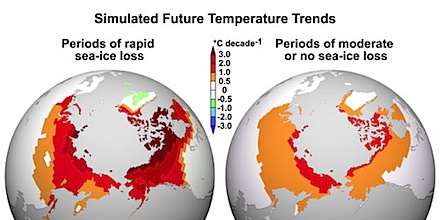

For REM, it “starts with an earthquake, birds and snakes, an aeroplane“, for us, it looks like diminishing Arctic sea ice is the sign. Over at Open Mind, the blogger formerly known as Tamino looks in some detail at the sea ice/rapid warming paper I linked to yesterday. His post makes for sober reading. David Lawrence and his team at NCAR and the NSIDC examined runs of the NCAR-based CCSM climate model that included episodes of rapid sea ice loss, and looked at what happened to climate of the Arctic during those periods. They found that the rate of warming increased 3.5 times faster than the average rate models project over the coming century. From the press release:

For REM, it “starts with an earthquake, birds and snakes, an aeroplane“, for us, it looks like diminishing Arctic sea ice is the sign. Over at Open Mind, the blogger formerly known as Tamino looks in some detail at the sea ice/rapid warming paper I linked to yesterday. His post makes for sober reading. David Lawrence and his team at NCAR and the NSIDC examined runs of the NCAR-based CCSM climate model that included episodes of rapid sea ice loss, and looked at what happened to climate of the Arctic during those periods. They found that the rate of warming increased 3.5 times faster than the average rate models project over the coming century. From the press release:

While this warming is largest over the ocean, the simulations suggest that it can penetrate as far as 900 miles inland. The simulations also indicate that the warming acceleration during such events is especially pronounced in autumn. The decade during which a rapid sea-ice loss event occurs could see autumn temperatures warm by as much as 9 degrees F (5 degrees C) along the Arctic coasts of Russia, Alaska, and Canada.

This is what it looks like in their nifty graphic:

This is what we saw last winter.

Looks as though the process the paper describes is already under way. Canada’s a bit cooler, but then it still has some ice left at the moment…

And the end of the world? Go and re-read my recent post on methane hydrates in the shallow seas north of Siberia. Consider what Lawrence et al have to say about permafrost. Then ponder the meaning of “positive feedbacks in the carbon cycle”. What’s happening up North could make any efforts to reduce global emissions irrelevant, or at best, mean that reaching a relatively low stabilisation target (450ppm?) suddenly a lot harder. Just to make things even harder, we have 30 years of warming to go, even if we could stabilise atmospheric greenhouse gases today.

I’m going to enlarge my veggie garden, and re-examine my thoughts on resilience as a response to climate change.

[Update: Joe Romm at Climate Progress has good coverage.]

[Update 2: Nature‘s In The Field blog reports reactions to the Lawrence et al paper from aboard a ship cruising the Arctic, and in passing confirms some of my thoughts…]

It’s a gas, gas, gas

It’s not good news. The USA’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has produced its annual report on greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere, and carbon dioxide concentration continues its accelerated growth. And there are signs that methane levels are beginning to rise, after a decade of remaining more or less static. The BBC reports:

It’s not good news. The USA’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has produced its annual report on greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere, and carbon dioxide concentration continues its accelerated growth. And there are signs that methane levels are beginning to rise, after a decade of remaining more or less static. The BBC reports:

NOAA figures show CO2 concentrations rising by 2.4 parts per million (ppm) from 2006 to 2007. By comparison, the average annual increase between 1979 and 2007 was 1.65ppm.

The methane rise is worrying because it’s a very powerful greenhouse gas (23 times as effective at trapping heat as CO2), and there are a number of positive feedbacks that could come into play as the planet warms. From the NOAA release:

Rapidly growing industrialization in Asia and rising wetland emissions in the Arctic and tropics are the most likely causes of the recent methane increase, said scientist Ed Dlugokencky from NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory. â€We’re on the lookout for the first sign of a methane release from thawing Arctic permafrost,†said Dlugokencky. “It’s too soon to tell whether last year’s spike in emissions includes the start of such a trend.â€

Permafrost is one thing, methane hydrates are another. Sometimes called burning ice, methane hydrates (aka clathrates) are a mixture of ice and methane that exist in large quantities on the sea floor – and there are particularly large amounts in the shallow Arctic seas north of Russia and Siberia (more info at Climate Progress). At the recent European Geophysical Union conference in Vienna, a Russian scientist discussed the issue. From SpiegelOnline:

In the permafrost bottom of the 200-meter-deep sea [off the northern coast of Siberia], enormous stores of gas hydrates lie dormant in mighty frozen layers of sediment. The carbon content of the ice-and-methane mixture here is estimated at 540 billion tons. “This submarine hydrate was considered stable until now,” says the Russian biogeochemist Natalia Shakhova, currently a guest scientist at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks who is also a member of the Pacific Institute of Geography at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Vladivostok.

The permafrost has grown porous, says Shakhova, and already the shelf sea has become “a source of methane passing into the atmosphere.” The Russian scientists have estimated what might happen when this Siberian permafrost-seal thaws completely and all the stored gas escapes. They believe the methane content of the planet’s atmosphere would increase twelvefold. “The result would be catastrophic global warming,” say the scientists.

The SpeigeOnline article is worth reading in full. Shakova’s observations of methane emissions hint at an explanation for the increase in global atmospheric methane. If that’s the case – and its too early to say for sure – then we may be seeing the beginnings of one of the most worrying of the positive carbon cycle feedbacks – one that could potentially make anything we do to cut CO2 emissions the equivalent of pissing in the wind.

[Hat tip for the Spiegel piece to No Right Turn – I’m frankly amazed the EGU paper hasn’t had much more coverage in the world’s media.]

[Update for the interested: The EGU abstract for Shakhova’s paper is here [PDF]. Here’s the last few words:

“…we consider release of up to 50 Gt of predicted amount of hydrate storage as highly possible for abrupt release at any time. That may cause ~ 12-times increase of modern atmospheric methane burden with consequent catastrophic greenhouse warming.”

“Abrupt release at any time”. That’s truly alarming.]

Winter wonderland

Climate cranks are keen to paint the last northern hemisphere (boreal) winter as unusually cold – a clear sign, they say, that “global warming is over”, and that global cooling has begun. Every crank’s at it: Bob Carter at Muriel’s place, Gerrit van der Lingen in an article in a Christchurch magazine and Vincent Gray in a submission to the select committee looking into the Emissions Trading Bill. It’s nonsense. The winter was cooler than many recent ones – but still 16th warmest, according to NOAA. A strong La Niña is cooling the tropical Pacific, and dragging the global average down, the precise converse of the strong El Niño that made 1998 so hot. In other words it’s weather noise, not long term change, as Stu Ostro explains at the Weather Channel. However, the cranks are right about one thing: last winter was unusual, but not for the reasons they think. In this post, I want to explore some of the reasons why this winter was out of the ordinary, and why I think it may demonstrate that rapid climate change is happening now. It’s an expanded version of how I began my last two talks…

Climate cranks are keen to paint the last northern hemisphere (boreal) winter as unusually cold – a clear sign, they say, that “global warming is over”, and that global cooling has begun. Every crank’s at it: Bob Carter at Muriel’s place, Gerrit van der Lingen in an article in a Christchurch magazine and Vincent Gray in a submission to the select committee looking into the Emissions Trading Bill. It’s nonsense. The winter was cooler than many recent ones – but still 16th warmest, according to NOAA. A strong La Niña is cooling the tropical Pacific, and dragging the global average down, the precise converse of the strong El Niño that made 1998 so hot. In other words it’s weather noise, not long term change, as Stu Ostro explains at the Weather Channel. However, the cranks are right about one thing: last winter was unusual, but not for the reasons they think. In this post, I want to explore some of the reasons why this winter was out of the ordinary, and why I think it may demonstrate that rapid climate change is happening now. It’s an expanded version of how I began my last two talks…