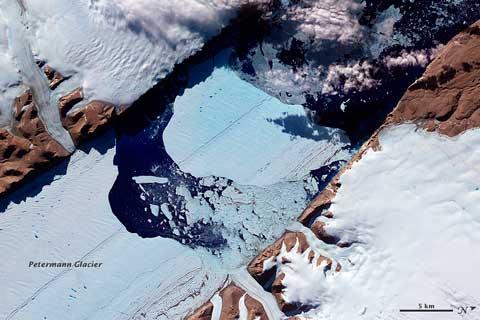

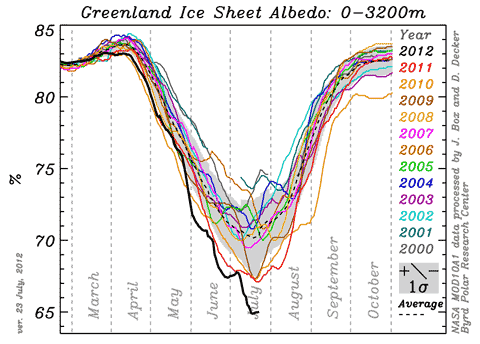

July has been an amazing month in Greenland. The Petermann Glacier has given birth to another huge ice island — taking its terminus further back up its fjord than at any time in the last 100 years (at least), record high temperatures have been recorded at the summit of the ice sheet at 3,200 meters, initiating surface melt over the whole vast sheet, ice sheet albedo has plummeted, and the Jakobshavn Isbrae’s calving front has retreated into the ice sheet.

The best coverage of the Petermann event, as on most matters to do with the Arctic summer and sea ice melting season is to be found at Neven’s Arctic Sea Ice blog. It’s well worth reading the comments under the Petermann post there, to get a really informative picture of what’s being going on. Here’s a description by Dr Andreas Muenchow ((Andreas provides great coverage of the Petermann glacier at his blog — perhaps unsurprisingly, as he’s on his way up there to recover instrumentation soon.)) of what the calving would have been like:

I described the Petermann calving to some media folks as a gentle and very quiet affair similar to a rubber duckie pushed out to sea from the deck of a flat pool.

Some duckie, some pool…

Further south, the the “root” of the Jakobshavn Isbrae has enlarged significantly, with the calving front of Greenland’s most productive glacier retreating further into the ice sheet. The “blink” image I’ve cobbled together (left) shows day 203 of this year compared with day 202 of last year ((Source: 2012, 2011.)). The difference is large and very obvious. Greenland specialist Dr Jason Box was flying out of Ilulisat shortly after the retreat earlier this month, and snapped the photo below out of the window of his plane. As he commented on Facebook, it looks like the glacier has divided into two streams.

Further south, the the “root” of the Jakobshavn Isbrae has enlarged significantly, with the calving front of Greenland’s most productive glacier retreating further into the ice sheet. The “blink” image I’ve cobbled together (left) shows day 203 of this year compared with day 202 of last year ((Source: 2012, 2011.)). The difference is large and very obvious. Greenland specialist Dr Jason Box was flying out of Ilulisat shortly after the retreat earlier this month, and snapped the photo below out of the window of his plane. As he commented on Facebook, it looks like the glacier has divided into two streams.

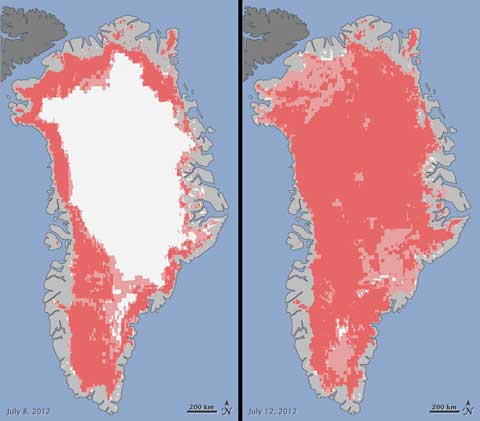

Up at the summit of the Greenland ice sheet at 3,200 metres, a new high temperature record of 3.6ºC was set on July 16, hard on the heels of four days in row of temperatures above freezing, from July 11 to 14. Considering that temperatures above zero had only been recorded four times in the preceding 12 years, this amounted a remarkable heatwave, and triggered an astonishing melt record.

This NASA graphic shows how the melting surface, shown in shades of red, spread over the whole surface of the ice sheet from July 8 to July 12. This amounts to “the largest extent of surface melting observed in three decades of satellite observations”, according to NASA. The last such melting event occurred in 1889, and ice cores show that they occur every 150 to 250 years. However, given the steady increase in melt area over the last decade, and the precipitous drop in ice sheet albedo (see below), especially at high altitudes, it may not be 150 years before such a melt happens again.

The last time I looked at this extraordinary summer in Greenland, it was to report Jason Box‘s view that “it is reasonable to expect 100% melt area over the ice sheet within another similar decade of warming”. It took two weeks to come true. Forgive me if I find that alarming.

A valuable review,

A valuable review,