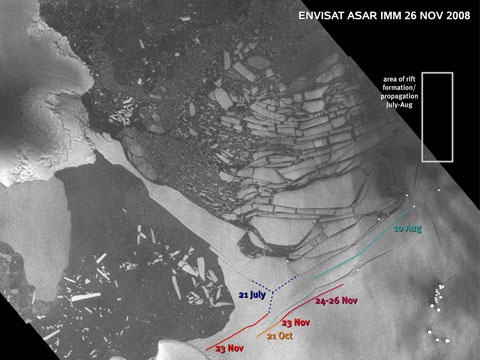

Summer’s arriving on the Wilkins ice shelf, and its disintegration continues. New cracks are threatening to destroy the ice “bridge” that’s been holding the ice shelf pinned between Charcot Island (top left) and the Antarctic peninsula. This picture, captured by the European Space Agency’s ENVISAT satellite on November 26, shows the new cracks (coloured lines) and the dates they first appeared (NASA version here). If the chunk of ice under “21 July” breaks away, the long thin bridge will lose support and follow suit, the ESA analysts say.

Meanwhile, a team lead by Richard Alley at Penn State has worked out that ice shelf calving – where icebergs break away at the edge of an ice shelf – is critically influenced by the rate at which the ice shelf is spreading out. The PSU release notes:

For iceberg calving, the important variable — the one that accounts for the largest portion of when the iceberg breaks — is the rate at which ice shelves spread, the team reports in the Nov. 28 issue of Science. When ice shelves spread, they crack because of the stresses of spreading. If they spread slowly, those cracks do not propagate through the entire shelf and the shelf remains intact. If the shelf spreads rapidly, the cracks propagate through the shelf and pieces break off.

When ice shelves break up, the glaciers that feed them can speed up noticeably, dumping more ice into the ocean. Over recent years, the role of water as a lubricant for glacier flow has been receiving a lot of attention (rubber ducks were recruited as under ice research tools in Greenland this year), and the BBC reports that a sub-glacial “flood” under the Byrd Glacier which feeds ice at the rate of about 20 billion tonnes a year into the Ross ice shelf caused that to increase to 22 billion tonnes over 2006. It has since returned to normal.

Up north, the NSIDC reports (Dec 3) that it continues to be warmer than average, even though the sea ice is now covering the whole Arctic ocean.

The latest satellite data shows that this summer’s snowmelt in northern Greenland was “extreme”, according to Marco Tedesco, assistant professor of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences at The City College of New York. From the press release:

The latest satellite data shows that this summer’s snowmelt in northern Greenland was “extreme”, according to Marco Tedesco, assistant professor of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences at The City College of New York. From the press release: