This column was published in the Waikato Times on March 16.

This column was published in the Waikato Times on March 16.

The media has paid disproportionate attention to an error in the monumental 2007 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In a chapter surveying the possible future impacts of climate change on the Asian region the report included a prediction that the Himalayan glaciers could melt by 2035. The glaciers will certainly melt if we continue on our current course, but not as soon as that. This was a mistake which the IPCC has acknowledged and regretted. Not too bad in a volume of 3000 pages, but a mistake that shouldn’t have occurred and wouldn’t have if procedures had been properly applied.

Since then there have been regular media “revelations” claiming other errors as well. For all the fanfare with which they have been produced these have so far turned out to hinge on little more than minor technicalities. They cause much excitement in the denialist community, but they amount to nothing of consequence.

Overstatement is what the IPCC is being accused of. But the reality is that its report is generally conservative and cautious and in one very important matter likely to have understated a real danger ahead. That is sea level rise.

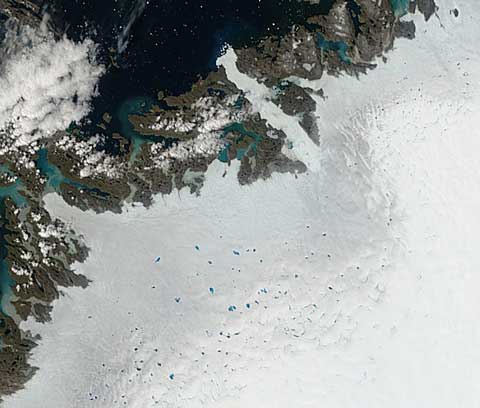

The IPCC does predict sea level rise in the century ahead, somewhere between 18 and 58 centimetres, depending on how high the level of greenhouse gases is allowed to climb. It sounds reassuringly manageable. But this predicted rise comes only from a combination of thermal expansion of the oceans because of warmer temperatures, and the continued slow melting of glacier ice. It assumes there will be no increase in the rate at which melting has occurred in the great ice sheets of Greenland and the Antarctic.

Time has passed, and it is now widely accepted in scientific circles that there is reason to expect a significant acceleration in the rate at which the Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets lose mass to the sea. The dynamics of ice movement are beginning to be better understood, and they are not reassuring. Those massive ice sheets are seemingly not as impervious as once thought and their melting not necessarily a slow predictable linear process. Disintegration may be a more accurate word than melting.

If the IPCC predictions are too cautious, what level of rise is now being considered likely in this century? One metre say some. Others say that’s still not allowing sufficiently for the acceleration likely to build, and recommend planning for a two metre rise. James Hansen of NASA is prepared to consider five metres as a real possibility, though he doesn’t offer that as a prediction..

Of all the predicted impacts of climate change, sea level rise is the one that I find most unnerving. Its effects on human populations are distressing to contemplate. The deltaic nations such as Egypt, Vietnam, Bangladesh and Myanmar will be badly hit. Some atoll nations will disappear. Countries with large low-lying coastal plains, such as the US, China and Brazil will be faced with tremendous disruption. Some great cities will be severely threatened, including Miami, New York, Tokyo and Amsterdam. It won’t be all that straightforward in New Zealand for that matter – a one metre sea level rise would put Tamaki Drive under water for example.

And it’s not the kind of damage that can be undone. How could we get water to return to the ice sheets? That’s why it is so important that we stop it happening in the first place. Any suggestion that a minor error in the IPCC report has somehow put the urgency of that task into question is out of touch with reality.

********************

It is likely that this is the last in the series of columns I have been invited to write for the Waikato Times over the past couple of years. The columns are directed to the general public, not Hot Topic readers, but they may have been useful here in indicating what can be written in public forums. It’s well worth anyone’s effort to get the message across in newspapers. I often wish there were more scientists writing in that medium, though I know it can be difficult to secure a space for opinion pieces. There are always the letters to the editor, which journalists tell me are popular with readers. The company there can sometimes be embarrassing, but if you’re willing to take that risk a clear statement on climate change will receive wide attention. It has been quite depressing to see in our local paper far more letters (often muddled) from contrarians than from those who take climate change seriously.

Like this:

Like Loading...

This column was published in the Waikato Times on March 16.

This column was published in the Waikato Times on March 16.