Kevin Anderson from the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change at the University of Manchester has been sounding alarms about the inadequate rate of reduction of greenhouse gas emissions for some years now. He’s done it again in a sobering paper written with colleague Alice Bows and recently published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (free access).

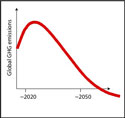

A Guardian article this week indicates some of the gist of the paper. Anderson points out that that policy advisers and policy makers are working on the basis of naïve and inappropriate assumptions which simply don’t obtain in reality. Growth rates in emissions are actually much higher than those used by most Integrated assessment models (IAMs) employed by researchers today, where climate change data is integrated with economic data. Emission peaks, even on an optimistic reckoning are not likely before 2020-2030 whereas most IAMs estimate 2010-2016. The IAMs also assume untested geoengineering, and a high penetration of nuclear power alongside untested ‘carbon capture and storage’ technologies.

Anderson’s calculations have shown that, if we want to aim for a high chance of not exceeding a 2 degree increase in global temperature by the end of the century, our energy emissions need to be cut by nearer 10% annually rather than the 2–4% that economists say is possible with a growing economy.

The models are producing politically palatable results. However, the reality is far more depressing and unfortunately many scientists are too afraid to stand up and say so for fear of being ridiculed.

“Our job is not to be liked but to give a raw and dispassionate assessment of the scale of the challenge faced by the global community.”

Because policy makers are living with false hopes they are not engaging with the sweeping changes necessary for industrialised nations to drastically reduce their emissions.

“This requires radical changes in behaviour, particularly from those of us with very high energy consumption. But as long as the scientists continue to spread the message that we will be ok if we all make a few small changes, then climate change will never be on top of the policy agenda and we will fail to meet our international commitments to avoid a 2 degree rise.”

Climate change is not a problem to be addressed in the future, but a cumulative problem that needs to be tackled now. And this can only be done if researchers use realistic data and report brutally honest results, no matter how disturbing or depressing.

To turn to the paper. It points out that though the Copenhagen Accord reiterated the commitment to hold the increase in global temperature below 2 degrees, it focused on global emission peak dates and longer-term reduction targets instead of facing up to cumulative emission budgets. That focus belies seriously the scale and scope of mitigation necessary. There was also lack of attention to the pivotal importance of emissions from non-Annex 1 (developing) nations in shaping available space for Annex 1 (developed countries) emission pathways. The paper provides a cumulative emissions framing to show what rapid emissions growth in nations such as China and India mean for mitigation rates elsewhere.

The consequence of focusing on end-point targets rather than facing up to emission pathways is that there is now little to no chance of maintaining the global mean surface temperature at or below 2 degrees.

“Although the language of many high-level statements on climate change supports unequivocally the importance of not exceeding 2 degrees, the accompanying policies or absence of policies demonstrate a pivotal disjuncture between high level aspirations and the policy reality.”

In essence we are putting off what must be faced up to now:

“In general there remains a common view that underperformance in relation to emissions now can be compensated with increased emission reductions in the future. Although for some environmental concerns delaying action may be a legitimate policy response, in relation to climate change it suggests the scale of current emissions and their relationship to the cumulative nature of the issue is not adequately understood.”

We are also relying on an outdated understanding of the likely severity of the impacts of a 2 degree rise in global temperature:

“…it is reasonable to assume…that 2 degrees now represents a threshold, not between acceptable and dangerous climate change, but between dangerous and ‘extremely dangerous’ climate change; in which case the importance of low probabilities of exceeding 2 degrees increases substantially.”

In relation to economic growth, the paper observes that if only a 2-4% level of emission reductions is compatible with economic growth, then it appears that:

“…(extremely) dangerous climate change can only be avoided if economic growth is exchanged, at least temporarily, for a period of planned austerity within Annex 1 nations and a rapid transition away from fossil-fuelled development within non-Annex 1 nations.”

The paper’s judgement as to the reality underlying the political talk:

“Put bluntly, while the rhetoric of policy is to reduce emissions in line with avoiding dangerous climate change, most policy advice is to accept a high probability of extremely dangerous climate change rather than propose radical and immediate emission reductions.”

The reader won’t argue with the authors’ description of their assessment of the climate challenge as “stark and unremitting”.

But they deny any negative intention:

“However, this paper is not intended as a message of futility, but rather a bare and perhaps brutal assessment of where our ‘rose-tinted’ and well intentioned (though ultimately ineffective) approach to climate change has brought us. Real hope and opportunity, if it is to arise at all, will do so from a raw and dispassionate assessment of the scale of the challenge faced by the global community. This paper is intended as a small contribution to such a vision and future of hope”

Hot Topic readers may recall that Clive Hamilton’s book Requiem for a Species, reviewed here, drew on an earlier 2008 paper by Anderson and Bows and quotes Anderson at the 2009 Oxford conference where climate scientists looked at the implications of a 4 degree increase in global temperature: “The future looks impossible.” It’s a pretty slim hope that Anderson allows, but he’s right to puncture the false ones.