Wine grapes are a climatically sensitive crop grown across a fairly narrow geographic range. Growing season temperatures for high-quality wine production is generally limited to 13–21°C on the average. This currently encompasses the Old World appellation regions of France, Italy, Germany, Spain and the Balkans, and those developing New World regions in California, Chile, Argentina, southern Australia and New Zealand.

Wine grapes are a climatically sensitive crop grown across a fairly narrow geographic range. Growing season temperatures for high-quality wine production is generally limited to 13–21°C on the average. This currently encompasses the Old World appellation regions of France, Italy, Germany, Spain and the Balkans, and those developing New World regions in California, Chile, Argentina, southern Australia and New Zealand.

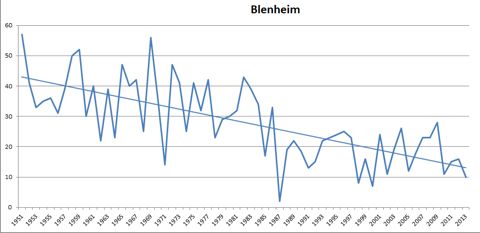

Speaking at the International Masters of Wine Symposium last month in Florence in Italy, professor Greg Jones, the wine climate specialist from the University of Southern Oregon, noted that the overall growing season temperature trend was upwards. This is for numerous wine regions across the globe from 1950–2000, by 1.3°C. Greater growing season heat accumulation with warmer and longer seasons has occurred. At the same time frost days (days below 0°C) have decreased from 40 to around 12 per year at Blenheim.

There has been a decline in the number of days of frost that is most significant in the dormant period and spring, earlier last spring frosts, later first frosts in autumn with longer frost-free periods. For example in Tuscany, the Chianti region of Italy, summer temperatures have increased by 2°C from 1955-2004. The warming is extending the world’s wine map into new areas such as British Columbia in Canada, Exmoor in England and into the southern Baltic.

The climate impacts of these warming trends in the Old World regions has been earlier budburst and flowering and altering ripening profiles which affect wine styles. For example, potential alcohol levels of Riesling at harvest in the Alsace region of France have increased by 2.5% (by volume) over the last 30 years and are highly correlated to significantly warmer ripening periods, earlier budbreak and flowering. In Napa, California from 1971-2000 average alcohol levels have risen from 12.5% to 14.8% while acid levels fell and the pH climbed. Soil temperatures are increasing in the wake of air temperatures, and will likely present numerous additional issues.

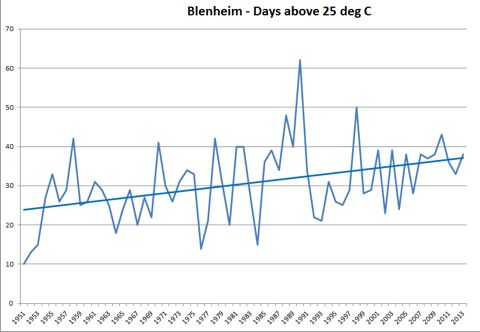

Similar warming trends are being observed in viticulture areas in New Zealand. For example in New Zealand’s largest wine production region in Marlborough, mean annual temperatures over the last 80 years have increased by 0.9°C, with the number of summer days (days above 25°C ) at Blenheim increasing from 24 to 36 a year.

At the same time frost days (days below 0°C) have decreased from 40 to around 12 per year at Blenheim.

Greg Jones noted that climate model projections by 2100 predict growing season warming of an additional 2.0–4.5°C on average. NIWA mid-range projections for the New Zealand wine grape areas are for a warming of 1°C by 2030 and 2°C by 2090.

The Florence Symposium turned its attention to how the European wine industry is preparing for a warmer world — and these lessons are very pertinent to our wine industry in New Zealand.

While challenges exist for all New Zealand wine regions, opportunities for a more sustainable industry are being addressed in the overseas industry and research communities. At the vineyard level the terrain slope (utilizing north rather than south facing slopes), training systems and vineyard design can be changed. For example many vine rows, have been oriented to maximize sunshine in places where this is no longer the optimal objective and shade will become a positive rather than a negative in many places.

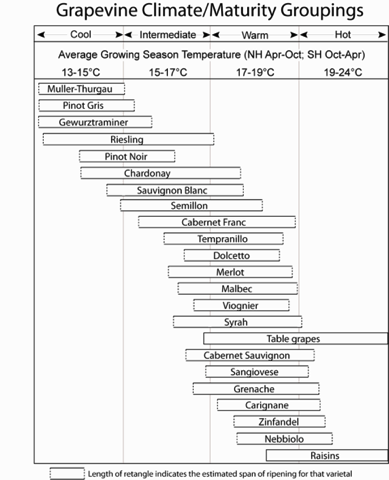

Another option is wine variety diversification. The Piedmont region of Italy is noted for its red wines which are made from either Dolcetto or Nebbiolo varieties. Although both varieties are grown over a relatively narrow climate range, Nebbiolo performs better in a warmer climate (17.8 to 20.4°C) with a long growing season. Dolcetto does better in a slightly cooler climate (16.4 to 18.4°C). This represents an expansion in quality and production potential.

There are about 5,000 or so varieties of grape that are known presently. In Bordeaux (France) the Parcelle 52 project, underway since 2009, is monitoring the performance of all sorts of locally unfamiliar grapes such as Grenache, Tempranillo and Georgia’s Saperavi in order to prepare for a hotter climate in the future.

Climate-maturity groupings based on relationships between plant life cycle requirements and growing season average temperatures for high to premium quality wine production in the world’s benchmark regions for many of the world’s most common cultivars. Diagram supplied by Greg Jones.

Other tips for a more glorious future in wine production from researchers include Rabigato and Alfrocheiro in Portugal; Sumoll, Escursac and one of the two different Maturanas in Spain; Counoise and Verdesse in France; Lagrein on the Italian mainland and Nieddera in Sardinia. The fastest growing varieties globally have been away from the cooler wine styles to Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and, especially, Tempranillo. The New Zealand wine industry can seize the opportunities with similar evaluations for each region with different varieties.

Finally the traditional appellation regions in Europe are in areas of significant topography and research programmes have been mapping potential new areas for production at higher elevations. New Zealand has a long latitude range and the South Island, in particular, has significant areas above 300 metres which can be utilised. This allows the migration of warmer wine styles south, with the cooler wine styles to higher elevations. For example, the MacKenzie Basin in inland Canterbury very likely has a significant potential for a future viticulture area – with a dry climate, hot summers and cold winters.

The Romans said: ‘Vino veritas — In wine there is truth’. The truth now is that the earth’s climate is changing much faster than the wine business, and virtually every other business is preparing for. The gradual nature of climate change should provide the industry sufficient time to develop and utilise some of the adaptation strategies discussed in Florence. A warming world represents opportunities for the New Zealand wine industry – both producers and growers.

This guest post is by Dr Jim Salinger, who is currently a visiting scientist at IBIMET-CNR, in Rome. He is conducting research on climate and wine quality in Tuscany. It’s a tough job, but someone’s got to do it… An edited version of this article originally appeared in the Lucy Lawless edition of the NZ Herald earlier this month.