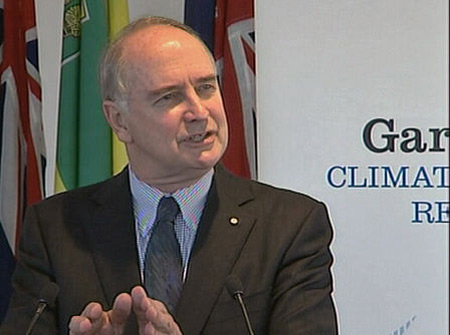

I appreciated the candidness with which economist Ross Garnaut introduced and concluded his recently released update on the science of climate change, one of a series of updates to his 2008 Review which have been commissioned by the Australian government. In the introduction he explains how he began his original Review with no strong views and no more than a common knowledge of climate change science. He read a fair bit of climate science in the course of preparing the Review, including paying due attention to sceptics with genuine scientific credentials, and his investigations led him to the premise for his Review that “on a balance of probabilities†the central conclusions of the mainstream science were correct.

I appreciated the candidness with which economist Ross Garnaut introduced and concluded his recently released update on the science of climate change, one of a series of updates to his 2008 Review which have been commissioned by the Australian government. In the introduction he explains how he began his original Review with no strong views and no more than a common knowledge of climate change science. He read a fair bit of climate science in the course of preparing the Review, including paying due attention to sceptics with genuine scientific credentials, and his investigations led him to the premise for his Review that “on a balance of probabilities†the central conclusions of the mainstream science were correct.

Since then he has moved in his thinking to regard it as highly probable that most of the global warming since the mid-20th century is human-caused. Further, he declares that he would now be tempted to say that those who think that temperatures and damage from a specified level of emissions over time will be larger than is suggested by the mainstream science are much more likely to be proven correct than those who think the opposite.

That personal view is illuminated but not expressed in the excellent survey which follows. It is an account, fully accessible to the lay reader, of where mainstream climate science stands at the present time. Its references include many papers published within the last couple of years. The main points have already been posted by Gareth and I’ll simply pick out one aspect before moving to Garnaut’s conclusion.

He discusses the appropriateness of the 2 degree rise in temperature widely accepted as the boundary beyond which climate change becomes dangerous, noting that since the Review there has been more comment in the mainstream science that a 2 degree  target may be insufficient to avoid ‘dangerous climate change’. He refers to the recent Anderson and Bows paper suggesting that, based on updates to the science, 2 degrees could now be considered as a threshold between ‘dangerous climate change’ and ‘extremely dangerous climate change’. Hansen’s 2008 proposal that 350 ppm carbon dioxide is the safe boundary receives mention, along with a supporting 2009 paper from Rockstrom. Although currently not likely to figure in policy action it “sits there as a warning of dangerâ€. However at current rates of emissions the global budget for an objective of 2 degrees will have been exhausted within a couple of decades. Indeed Garnaut considers it is now necessary to explore the implications of a global temperature rise of 4 degrees above pre-industrial, well beyond the experience of human civilisation.

The risks accompanying a 4 degree rise are considerable. There would be an 85 per cent probability of initiating large-scale melt of the Greenland ice sheet. 48 per cent of species would be at risk of extinction. 90 per cent of coral reefs would be above critical limits for bleaching. Accelerated disintegration of the west Antarctic ice sheet and changes to the variability of the El Niño – Southern Oscillation would be triggered. Terrestrial sinks such as the Amazon Rainforest would be endangered, becoming sources of carbon rather than sinks. Severe weather events would intensify. Immense changes in the capacity of parts of the earth’s surface to support substantial populations would place great strain on national and global political systems. He notes that recent science suggests that severe and catastrophic climate change outcomes may be triggered at lower temperatures than previously thought, further increasing the risks of catastrophic outcomes in a 4 degrees warmer world.

In the conclusion Garnaut highlights what has been apparent throughout his survey, that the science he accepted “on the balance of probabilities†for his Review has only grown stronger in the subsequent three years, and so far as his own personal intellectual journey is concerned it is now closer to the more stringent criminal law requirement of “beyond reasonable doubtâ€.

The most important and straightforward of the quantitatively testable propositions from the mainstream science have been confirmed or shown to be understated by the passing of time: the upward trend in average temperatures; the rate of increase in sea level.

The science’s forecast of greater frequency of some extreme events and greater intensity of a wider range of extreme events is “looking uncomfortably robustâ€.

Some measurable changes are pointing to more rapid movement towards climate “tipping points†than suggested by the mid-points of the mainstream science. He instances the rate of reduction in Arctic sea ice and the emergence of accumulations of methane in the atmosphere at a rate in excess of expectations.

“Regrettably, there are no major propositions of the mainstream science from 2008 that have been weakened by the observational evidence of these past two years.â€

He acknowledges that 450 ppm has now become a difficult target, given the slow progress on mitigation in the developed countries, but nevertheless counsels that it would be wise for Australians through their domestic actions and international interactions to work towards achieving that much. Â Along the way, he suggests, they can assess whether developments in knowledge have made the case that their national interest requires higher ambition.

In a final reflection he dwells on the fact that his update has shown that new observations and results of new research have all either confirmed established scientific wisdom, or shifted the established wisdom in the direction of greater concern. This pattern has been present for some time in the development of climate science. He wonders whether the reason for this may be professional reticence to step too far ahead of received wisdom in one stride, and draws attention to Hansen’s remarks in Storms of my Grandchildren on how scientific reticence may in some cases hinder communication with the public. Garnaut himself in his own field has had experience in the past of writing and speaking about what the 1978 reforms in China might mean for the Australian economy in terms which were criticised as implausible but which turned out to be understatements, and has wondered whether he was influenced into understatement by repeated criticisms of optimism. Has something similar been at work for climate scientists? And is understatement making it difficult for the full risks of climate change to be appreciated by the lay public, himself included?

He notes how in the published scholarly literature scientific sceptics are making fewer and weaker claims as the mainstream science moves away from them. At the other end of the spectrum, the scholars who were away from the mainstream in the other direction have found the mainstream science moving towards them. They have tended to remain more active in genuine scientific research and publication.

He draws the reluctant conclusion that there must be a possibility that scholarly reticence, extended by publications lags, has led to understatement of the risks. Although he doesn’t advocate clutching for knowledge outside the mainstream wisdom he speaks of the need to be alert to the possibility that reputable science will in future suggest the need for much stronger and much more urgent action on climate change even than is warranted from today’s peer-reviewed published literature. One presumes he would be willing in such case to urge such action, no matter how difficult it might seem economically.

Garnaut’s update shows him observant and respectful of the science of climate change. It’s no more than one might reasonably expect of intelligent and well educated lay people, and it’s a sad commentary on our intellectual life that it occasions remark. It’s an essential credential for a policy adviser and one wishes it were more widely apparent among economists.

Garnaut is like Nicholas Stern in respect to the science. Coincidentally the Wonk Room is carrying a recent interview with Stern (in three parts here, and here, with one to come) in which he too refers to the growth in scientific understanding since the Stern Review was published in 2006 and states that his report underestimated the risks now apparent. He briefly describes some of them and sombrely speaks of the risk of global war over the next century “because you’ve got hundreds of millions of people, perhaps billions of people movingâ€.  Needless to say he continues to urge action now in an industrial revolution which will bring emissions down rapidly over the next forty years at a reasonable cost for a massive risk reduction.

While this is not directly on Garnaut, but I just listened on National Radio to Karthryn Ryan’s interview of Yvo De Boer, Former Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

This is one of the best records on where it is all at. It was a pleasure to listed to De Boer’s clear and succinct analysis.

http://podcast.radionz.co.nz/ntn/ntn-20110315-1005-Feature_Guest_-_Yvo_de_Boer-048.mp3

Great post, Bryan!

Yet again we are struck by the abrupt distinction between the real world of grown-ups where the actual science and risk assessment is done, and Shouty World where the emptiest vessels persist in making the most noise.

On the topic of risk and in want of a better place at the moment to place this link, here is one that probably sums up the risk assessment of the nuclear issues in comparison with the immediate risks of fossil fuel burning in a pretty clear way. This discussion is an important one if want to remain cool headed about future energy supply options in the light of what is going on in Japan at the moment.

http://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/post.cfm?id=beware-the-fear-of-nuclearfear-2011-03-12

An interesting read. That’s the case I’d be making if I were a proponent – though I think the implication that it might somehow be invalid to compare this to Three Mile Island is simply wrong. But I note the article was written on the 12th so we can only assume the author was unaware of current developments.

That odd breed – AGW deniers who looooove nukes; there’s a surprising number of them – must be put in a funny position by all this, because the only card the industry has left is AGW.

It’s that simple. On the basis of the Japanese crisis to date I could train my cat to successfully oppose any proposed nuclear plant development pretty-well anywhere for the next few years, and if there is a meltdown in any of the stricken reactors I reckon young Basil could even be getting existing plants decommissioned left right and centre in between bouts of refusing to eat his food. My point is that the ACF and FoE have plenty of people who are at least as capable as my cat. In fact, they are preparing to outshine him as we speak…

And the only answer that can possibly be had to objections that it’s all too bloody dangerous is an and/or deniers will despise – we either have to do it because of AGW, or because the oil’s going to run out. Or, obviously, both. Anyone who denies the reality of both has just conceded the entire nuclear debate to my cat and Ian Lowe.

Another glaringly obvious point for pro-nuke deniers. You just spent years deriding mainstream scientists and telling us they were venal charlatans conspiring against the public good. And promoting a bunch of third-rate hacks we were supposed to accept as authorities in their place. Don’t come blubbing to me when the nasty stupid public misunderstands the nuclear issue and just won’t accept the ‘proper’ science but listens to Greenpeace instead!

And, seriously, TEPCO’s um, shall we say ‘less-than-forthright’?, behaviour has been a gift to anti-nuclear advocates everywhere!… but how could it be otherwise? That’s how corporations are. I think the real problem is that nuclear power is fundamentally a resource for people who are waaaay more perfect than any actually existing human society.

Haven’t noticed any squawking recently from the Libertarianâ„¢ ‘we don’t need no regulations’ brigade, either. Staying at home to clean all those litres of egg from their faces, no doubt… could they possibly be any more stupid or wrong?

What’s the risk of a magnitude 9 earthquake in France, Bill? Maybe your cat knows something I don’t, but I don’t exactly see how the situation in Japan means that all nuclear power stations have suddenly become earthquake-prone.

Risk assessment is something that people, and cats, are extraordinarily bad at. Most people trust their visceral reaction to risk over anything their brain tells them, which is why most people look nervous and cover their gonads whenever the word “nuclear” is mentioned.

Rational analysis, on the other hand, will tell you that the risks from continuing to pump CO2 into the atmosphere far outweigh the risks of nuclear power, as this article shows.

I think the nuclear issue is indeed going for a while at least the way Bill put it so well. Even his cat could organize a public revolt against any idea to increase or promote nuclear energy right now. That is simply a fact of the mass psychology that we are facing after all this will have settled, and it seems to get worse by the hour as we speak.

But the real question of merit is: Would Bills Cat be right in condemning nuclear power or has it used sound logic to do so?

The facts so far:

1) World wide hundreds of thousands die every year from the ill health effects of dirty fossil fuel burning.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air_pollution#Health_effects

2) Coal power plants release huge amounts of radionuclides into the atmosphere: “A 1,000 MW coal-burning power plant could have an uncontrolled release of as much as 5.2 metric tons per year of uranium (containing 74 pounds (34 kg) of uranium-235) and 12.8 metric tons per year of thorium.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fossil_fuel_power_station#Radioactive_trace_elements

This is due to the “trace” amounts of these elements and isotopes in coal ore and there is nothing that can be economically done to remove these. These numbers are generally not known or discussed.

3) Chernobyl, the worst so far (hopefully it stays that way) nuclear accident may cause over the next decades a total of 4000 additional death due to cancer. This is a horrendous amount. But back to FF burning, if added to the six digit figure of annual death due to particulate emissions of FF burning and they won’t even make a blip on the statistics visible to the naked eye.

In fact, if all the nuclear power stations world wide were replaced with coal fired stations, the health effect would be catastrophic in numbers in comparison, even if we had one Chernobyl causing 4000 death annually!

Hmm… nuclear dangers are pushing all the buttons of a worst case psychological fear generator: You can’t see it, You might ingest it, It might carry on working its ill effects inside you and you can not do anything about it.

In comparison you can see the dirty exhaust stack of the truck in front of you, and you falsely assume, that therefore that won’t be much of a bother as you could stay further back with your car…

I am not sure. I am a Physicist, so I guess I have some handle on the technological issues of nuclear power and perhaps some bias this way to think that it can and perhaps should play an important role in our future energy mix.

I hope that society won’t succumb to Bill’s cats revolution and that clear heads and sound scientific analysis shall prevail as otherwise we will tip the proverbial baby out with the bathwater.

You might also be interested to know that Wind Power is not exactly safe. Many of these turbines are in difficult to reach areas and also in hazardous offshore locations.

A summery of wind accidents and fatalities is here

http://www.caithnesswindfarms.co.uk/page4.htm

(The trend is as expected – as more turbines are built, more accidents occur. Numbers of recorded accidents reflect this, with an average of 16 accidents per year from 1995-99 inclusive; 48 accidents per year from 2000-04 inclusive, and 103 accidents per year from 2005-10 inclusive.)

There’s a big difference between workers in the field dying in accidents, and innocent members of the public being killed by toxic pollution out of their individual control. Just ask the nuclear industry right now; they have some of the best safety statistics in terms of fatalities per GWh of power generated, but are their stocks saleable?

Your source states that 53 workers and 21 innocent people have died because of Wind Power over ~15 years. You might be able to put that in a “blood currency” and show it is more deadly than oil or nuclear overall. But it’s still going to be far less scary than 4,000 clustered deaths or dead patches of ocean due to oil slicks.

…ya, John the D, and then again about 1.2 million were killed in road accidents in 2004 (a year for which some global figures were available).. so perhaps the first measure dear John to make you feel safer would be to abandon private transport by motor vehicle…. (would solve a few other issues too….)

Of cause I am just kitting….. 😉

Oh and hot from the press: 12 people are killed per year on average by flying kites, twice the wind farm fatalities…

http://www.kiteman.co.uk/DidYouKnow.html

This is clutching at straws!

“Wind Accidents” include,

“An employee broke his left leg when a wind turbine control panel he was removong (sic) from a packing crate tipped over.”

Did you look at this before you posted the link?

Possibly so but but what startles me is the scale of failure in Japan in thier backup systems. Yes they have been inundated by a Tsunami but that only explains part of it and should have been allowed for its a known risk in Japan. Plus valves have stuck, all sorts of stuff possibly unrelated to the tsunami.

You wonder about backup systems in France etc. Human failings, complex systems that always seem to seize up and fail when a real problem occurs.

Backup systems are only as good as the people who run them, nigel.

http://www.gregpalast.com/no-bs-info-on-japan-nuclearobama-invites-tokyo-electric-to-build-us-nukes-with-taxpayer-funds/

Don’t know about you, but I’d prefer any sloppy engineering to be out there where I can see the rusting blades on the turbine.

Hey, I’m not saying my cat’s necessarily right, I’m just saying he’s been given the purrfect opportunity!….

Sure, there’s no risk of such an earthquake in France. Or maybe there’s a small risk of maybe a magnitude 4 quake. So what happens if a 5 hits the plant? How about localised flooding, storm-surges landslides etc. – when has the risk become so negligible it need not be mitigated against? In other words, how much protection is enough? How about the ‘unknown unknowns’ (I despised Rumsfeld, but what he was saying here wasn’t stupid at all!) My cat’s having a grand old time pointing this out at public meetings…

Joe Romm puts it rather well –

JohnQuixote, now you’re just being silly!

The advantage of nuclear energy is that it can produce vast amounts of electricity relatively cleanly and reliably. The downside is that when it goes wrong it goes very wrong and also people have a real fear and dislike of it.

The advantage of Hydro, Geothermal and Wind is that your production units are small and well spread out and if you get a problem it is very local and easily covered by other units of supply. The distribution network does not have to be as big as much more power is produced locally and the capital cost of each plant is smaller and not subject to planning delays and protests.

We have the Ngapha geothermal plant nearby, it is only 60 megawatts but it supplies our local needs and is very unobtrusive.

One solution suggested by current events it so throw every resource we have at developing a pill to prevent radiation sickness.

People are working on it:

http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-3748014,00.html

http://io9.com/#!376170/one-pill-could-cure-radiation-sickness

It seems a bit out there, but logic suggests that if it were possible it would be quite a game changer in terms of geopolitics and climate change? I would not expect Garnaut to mention it, but has anyone seen a serious discussion of the idea?

I realise this gets close to being off topic, but its hard to avoid given current events.

From what we know so far, the emergency power systems were not fit for purpose; they either failed of their own accord, or were located within reach of tsunami.

Exacerbating this design failure, mobile power plants apparently could not be used, as they were not plug-compatible with the plant electrics.

One wonders if the emergency systems had ever been tested against a power-loss scenario and, if not, why not?

In the old days, I expect the senior management of Tokyo Electric would be performing seppuku by now.

Instead of which it’s the poor brave bastards in the plants who are killing themselves…

The situation is much grimmer than I had initially thought.

Here is why:

The residual decay heat of a turned off reactor of this sort is about 0.5% of rated capacity now (four days after shut down) and still 0.25% of rated capacity by December 2011 as the slower decaying isotopes have a VERY LONG DECAY TAIL!

Expressed in MW of heat produced by radioactive decay in the elements this means that the fuel rods in the reactors are at the moment powering with about 10MW thermal heat flux!!! and end of the year with still about 5MW!!

5 MW heat energy is well enough to melt the rods in absence of cooling even after a year. This applies also to the rods that were removed from the reactor and stored in the cooling pond in reactor 4 which was down for maintenance. The cooling pond as it seems is perhaps destroyed or can not hold water. These rods of number 4 are basically as good as fully exposed to the environment at present and would reach temperatures >1500 C causing H2O splitting and hydrogen fires and melting.

The company says that they can not rule out that these elements might form a puddle that goes critical again! There are no control rods in the cooling pond and no shielding for anything like this. There would be no way to stop this if it was to happen.

Radiation levels at the plant boundary are reported at 1530 microsieverts/hour causing instant radiation sickness and probable long term death. Darn!

Source: http://mitnse.com/ (MIT nuclear department discussing the incident and consequences)

…correction, the 1530 microsievert/h, if correct and numbers seem to be fluctuating a lot, would only be 1.53 millisievert of cause that in itself would be one chest x-ray/h, so not necessarily deadly. But I guess the information coming from the plant is rather unreliable.

Interesting piece from yesterday from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists —

My cat and I are both inclined to agree.

I agree. The fact that the designers had overlooked the vulnerability of the cooling pond and its potential to turn into perhaps the focal point of a cascading incident like this is a sign that we indeed do not grasp the probabilities involved in all this effectively.

Also any high temp reactor accident can never be “tested” so all these designs fly blind by the guidance of some engineers calculations and judgments of what is possible or probable.

In 1970something sophisticated computer simulations were non-existent too which makes these designs especially suspect.

I think you’ve expressed it very well Bill. Let’s hope that “we” (Australasian context) are among those who don’t have to exercise nuclear options.

Can we take the Fukushima discussion to the latest Climate Show thread please: it’s on-topic there.

right on! Noise – being the whole point..

for what it is worth I’d harbored a view that Jones seeking a temperature trend line through all the stats noise was in point of opinion the model upon which the Shoutys, as you put it bill, congregated around and carried on about him..

of further interest perhaps is this link – http://solveclimatenews.com/news/20110318/google-climate-change-fellows-science-new-media – re a so-called new technology initiative which again makes highly relevant points..

Oops!

Above comment was thought to be replying directly to – bill @ March 15, 2011 at 12:35 pm.

I’ll add here how ‘fracking’ the nuke industry – advocates and acolytes – appears to look in the face of matters arising..