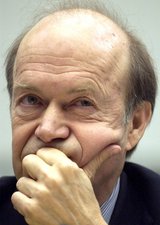

Paul Nurse is the new President of the Royal Society. His predecessor Martin Rees was firm in his insistence on the seriousness of climate science and climate change, and Nurse is equally so. In a striking BBC Horizon documentary Science Under Attack he examines why public trust in scientific theory appears to have diminished, especially in relation to climate change. The documentary is not available from the BBC for viewers outside the UK, but it has been uploaded to YouTube, broken into six segments. It is well worth an hour of viewing, but I’ll offer some comment on it here for those who don’t have the time.

Nurse is a geneticist and cell biologist, distinguished for his work in the discovery of the control which regulates cell division, for which he shared a Nobel Prize in 2001, and which is relevant to a better understanding of diseases like cancer. In this documentary he steps outside his lab to investigate how it is that climate science has come under attack and whether scientists are partly to blame.

The documentary opens and closes in the archives of the Royal Society which include among their books the manuscript version of Newton’s Principia Mathematica and the first edition of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, presented to the Society by the author. Nurse and the librarian pause over these two outstanding examples from the Society’s past of science fundamental to our understanding of the world, a useful backdrop to the programme’s investigation of why a well-established science, as climate science now is, should be leaving many people unconvinced or thinking it is exaggerated.

He visits NASA and talks with Robert Bindschadler, who shows him in visualisation how satellites (16-18 from NASA and a similar number from other agencies) circling the globe are gathering enormous amounts of data related to climate. Three quarters of a degree of warming over the last fifty years will be matched by at least another three quarters of a degree over the next fifty even if we do nothing more to modify the climate. Asked whether this could be a natural fluctuation Bindschadler acknowledges that there have been times in the past when the Earth has been warmer than it is today, with less ice and higher sea level, and times colder than it is today, with much more ice and lower sea level. However in the past climate changed very gradually whereas it’s now changing really fast, and it’s the pace of change that is so important in the climate change that we’re living through right now.

Nurse considers not only the NASA data but also the work of seven decades of research from scientists across the globe and concludes that the extent of the data gives us reason for confidence in the idea that the globe is warming and we are causing the change. Yet this evidence is clearly not convincing a substantial part of the wider public. And those who are sceptical turn to other scientists. Enter Fred Singer, who meets with Nurse over a cup of tea in a café and explains his theory that solar activity, not CO2, is the cause of warming which he regards as variable.

Nurse talks to viewers about the importance of the wider picture, which Singer ignores in his cherry picking. Things need to make sense together. Solar activity needs to be looked at in the context of all research. You cannot ignore the majority of available evidence in favour of something you would prefer to be true. Bindschadler comments that small variations in solar activity today don’t match up with the climate data. There’s no doubt, he says, that the sun is not the primary factor driving the climate change that we’re living through. It has to be the huge amounts of carbon dioxide our fossil fuel burning is putting into the atmosphere. You need to stand back and look at the big picture and there’s really no controversy if you do that.

“Who do you believe?” asks Nurse. If you’re not a scientist then ultimately it’s a question of trust. At this point he goes to the Climatic Research Unit at East Anglia University and talks with Phil Jones, the scientist who was accused in headlines, on the basis of stolen emails, of being at the centre of one of the worst scientific outrages of all time. Nurse points out there was no scientific scandal, as enquiries have established. At worst there was an understandable but perhaps less than wise resistance to meeting obviously engineered requests for information.

Nurse then visits James Delingpole, one of the journalists prominent in proclaiming the climategate email scandal. He is perfectly polite with Delingpole, but his gentle questioning elicits from the interviewee the brash certainties of a man who has no knowledge of the solidity of the scientific consensus on the causes of global warming but is an articulate and bellicose proponent of the theories of the deniers, accepting the few scientists among them as authoritative interpreters of the peer reviewed science which he himself doesn’t read. Nurse is surely right to see an unholy mix of the media and politics as distorting the proper reporting of science.

He acknowledges the problem of uncertainties, particularly in projecting the future and particularly in projecting cloud formation. But a fascinating picturing at NASA displays how the uncertainties are reducing. Bindschadler shows him a screen, along the upper half of which real global cloud data is pictured and in the lower half what the models predict would be happening at the same time. It’s a test of the models, and the level of their accuracy is astonishing to Nurse. Binsdschadler is clear there will always be some uncertainties because there are processes which are not fully understood, but by the measure of reducing uncertainties the science is making extraordinary progress.

There’s much more in the documentary than I have covered here, but hopefully this gives a sense of the thoroughness and reasonableness which marks Nurse’s investigation. He’s a person of intellectual substance who, in his own words has “an idealistic view of science as a liberalising and progressive force for humanity.”

I’ll conclude with a section of quotes I’ve transcribed from the latter part of the documentary, where he sums up what he has been seeking to communicate. First, on the centrality of peer review (irretrievably corrupted according to Delingpole) and the importance of scientific scepticism:

“As a working scientist I’ve learnt that peer review is very important to make science credible The authority science can claim comes from evidence and experiment and an attitude of mind that seeks to test its theories to destruction…Scepticism is very important…be the worst enemy of your own idea, always challenge it, always test it I think things are a little different when you have a denialist or an extreme sceptic. They are convinced that they know what’s going on and they only look for data which supports that position and they’re not really engaging in the scientific process. There is a fine line between healthy scepticism which is a fundamental part of the scientific process and denial which can stop the science moving on. But the difference is crucial.”

On complexity:

“There’s an overwhelming body of evidence that says we are warming our planet but complexity allows for confusion and for alternative theories to develop. The only solution is to look at all the evidence as a whole. I think some extreme sceptics decide what to think first and then cherry pick the data to support their case. We scientists have to acknowledge we now operate in a world where point of view not peer review holds sway.”

That means taking trouble to communicate:

“Scientists have forgotten that we don’t operate in an isolated bubble. We cannot take the public for granted. We have to talk to them. We have to communicate the issues. We have to earn their trust if science really is going to benefit society.”

It matters for the world:

“Over the next few years every country on the globe faces tough decisions over what to do about climate change. I’ve been thinking how scientists can win back the confidence we’re going to need if we’re going to make those choices wisely.”

He turns to the record of the Royal Society:

“350 years of an endeavour which is built on respect for observation, respect for data, respect for experiment. Trust no-one. Trust only what the experiments and the data tell you. We have to continue to use that approach if we are to solve problems such as climate change.”

That brings responsibility with it:

“It’s become clear to me that if we hold to these ideals of trusting evidence then we have a responsibility to publicly argue our case because in this conflicted and volatile debate scientists are not the only voices that are listened to.”

Politics enters the picture but scientists have to keep their focus:

“When a scientific issue has important outcomes for society then the politics becomes increasingly more important. So if we look at this issue of climate change that is particularly significant, because that has effects on how we manage our economy and manage our politics, so this has become a crucially political matter and we can see that by the way the forces are being lined up on both sides. What really is required here is a focus on the science, keeping the politics and keeping the ideology out of the way.”

But that doesn’t mean disengaging:

“Earning trust requires more than just focusing on the science. We have to communicate it effectively too. Scientists have got to get out there. They have to be open about everything that they do. They do have to talk to the media even if it does sometimes put their reputation at doubt because if we do not do that it will be filled by others who don’t understand the science and who may be driven by politics or ideology. This is far too important to be left to the polemicists and commentators in the media. Scientists have to be there too.”

Paul Nurse has certainly put himself there in undertaking this documentary. Needless to say it cut no ice with the affronted James Delingpole, but surely many viewers will have been impressed with the evidence urgently yet reasonably presented by this distinguished scientist, and equally impressed that he goes to such trouble to make it all accessible to the general public.

Like this:

Like Loading...

The Laird had been sat on his personal promontory for hours, staring out over the loch, an occasional tear rolling gently down his cheek. Scrotum had been quick to take him a generous snifter of the Queensland pineapple rum he’d enjoyed so much in the outback a year ago, but even the heady waft of tropical alcohol and memories of days in the Austral sun could not dispel Monckton’s black dog. The wrinkled retainer had seen the dog take him before, but this was no mere short-haired dachshund, it was the full weimaraner. Scrotum repaired to the library and opened Monckton’s laptop. A strange Roman script filled the screen…

The Laird had been sat on his personal promontory for hours, staring out over the loch, an occasional tear rolling gently down his cheek. Scrotum had been quick to take him a generous snifter of the Queensland pineapple rum he’d enjoyed so much in the outback a year ago, but even the heady waft of tropical alcohol and memories of days in the Austral sun could not dispel Monckton’s black dog. The wrinkled retainer had seen the dog take him before, but this was no mere short-haired dachshund, it was the full weimaraner. Scrotum repaired to the library and opened Monckton’s laptop. A strange Roman script filled the screen…

You may have noticed that New Zealand’s

You may have noticed that New Zealand’s

Don Easterbrook’s

Don Easterbrook’s