It is two and a half years since the landmark Stern Report to the UK government was released. It called climate change “the greatest and widest-ranging market failure ever seen” and concluded that the benefits of strong and early action to reduce emissions far outweigh the economic costs of not acting. At 700 pages it was a daunting document. Now Nicholas Stern has written a book which updates his thinking and explains it in terms which non-economists will readily be able to follow — The Global Deal: Climate Change and the Creation of a New Era of Progress and Prosperity (US edition – confusingly published in the UK under a different title Blueprint for a Safer Planet.) Stern has a long-standing involvement with efforts to overcome poverty in developing nations. He makes it clear from the start that combating climate change is inextricably linked with poverty reduction as the two greatest challenges of the century and that we shall succeed or fail on them together – to tackle only one is to undermine the other. This theme is frequently sounded in the book, and is an indication of the humanity which he brings to his task, as well as the realism.

Stern recognises we are on track to end-of-century temperatures of 4-5 degrees centigrade or higher relative to 1850, enough to rewrite the physical and human geography, with the prospect of massive and extended human conflict. He firmly dismisses those who deny the dangers and the urgency of action.

The target level he focuses on for risk reduction is a maximum 500 parts per million CO2 equivalent. (CO2e includes the greenhouse gases other than CO2 and 500 ppm is roughly equivalent to the more commonly used 450 ppm CO2. The current level of CO2e is estimated at around 430 parts per million.) The target of 550 ppm CO2e adopted by the Stern Report he now considers too risky. He notes that even at 500 ppm CO2e the risks are high – a probability of over 95% of a temperature rise greater than 2 degrees, but only a 3% chance of it being above 5 degrees. So although he uses the 500 ppm CO2e target for the purposes of the book he readily acknowledges the likely need for downward revision – probably to 400 ppm CO2e to have a fifty-fifty chance of limiting the temperature rise to 2 degrees.

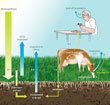

A very positive section outlines the technologies already available for the task and summarises what we must do under four headings: make more efficient use of energy; halt deforestation; put existing or close-to-existing technologies to work quickly, including carbon capture and storage; invest strongly in new technologies which are on the medium-term horizon. The resulting low-carbon world, ushered in by a new burst of innovation, creativity and investment, will be a very attractive one in which to live. “It is a world where we can realise our ambitions for growth, development and poverty reduction across all nations, but particularly in developing countries.” This is not a fancy. Previous examples of rapid change show it can be done. Stern’s contacts in the many places he visits and speaks leave him with a strong impression of the vast entrepeneurship and creativity which can be released given the right policy frameworks. This is one of the cheering themes of the book.

The cost is reasonable. Drawing on McKinsey analyses to discuss cost, he concludes that 2% of GDP per annum will do it, a level smaller than some which our economies already cope with in terms of exchange-rate movements or changes in trade terms. It can be thought of in terms of an extra six months for the world economy to reach the level of world income it would otherwise reach by 2050.

There is no ‘versus’ between mitigation and adaptation. Stern descibes several ways in which different countries are taking adaptation measures and makes it very clear that adaptation is particularly important for developing countries, hit earliest and hardest by consequences for which they bear no responsibility. He quotes Archbishop Tutu with approval: “I call on the leaders of the rich world to bring adaptation to climate change to the heart of the international poverty agenda — and to do it now, before it is too late.”

So far as Stern is concerned the ethical demand to act on climate change needs no further justification than that provided by the risks of inaction and the costs of action which he covers in the early chapters of the book. But because many economists use a more formal and model-based discussion of how to balance the costs of inaction against the cost of action he devotes 20 pages of the book to examining how and why a number of high-profile economic analyses have got things badly wrong. The costs of inaction are much larger than are understood by many of the economists who have argued for it. Even his own Stern Report is now shown to have been too cautious on the growth of emissions, on the deteriorating absorptive capacity of the planet, and on the pace and severity of the impacts of climate change. The “slow ramp” approach advocated by some of his critics would lead to concentration levels so high as to be unthinkable.

Policies need to be effective, efficient and equitable. Different countries can have different combinations of policies relating to carbon taxes, carbon trading on the basis of quotas, and regulation. But the overall level of ambition needs to be strong and equitable, and there must be a strong role for trading schemes which allow international trade in greenhouse gas reduction – this trade both improves efficiency and provides incentives for developing countries to join in international action. He has an excellent section on the conditions which will enable trading schemes to work to the desired end. The explanations of the necessity of international trading schemes as part of the mix for emission reduction were one of the highlights of the book for me, and made very clear the contribution that economists can bring to the enterprise.

We must have a global deal. The world needs an overall 50% cut in emissions by 2050 relative to 1990. Towards achieving this the developed countries need to agree to a 20% to 40% reduction in their emissions by 2020 and to 80% by 2050. Within this time frame they need to demonstrate that low carbon growth is possible and affordable. The developing countries need to commit, subject to the developed countries’ performance, to take on targets by 2020 at the latest. Their emissions should peak by 2030, or 2020 for the better-off among them. They should be integrated into trading mechanisms both before and after their adoption of targets.

In discussing funding he focuses on three areas. First, deforestation, responsible for 20% of global emissions. There is a need for strong initiatives, with public funding, to move towards halting deforestation now. We should prepare to to include avoided deforestation in carbon trading. Second, technologies must be developed and shared. Carbon capture and storage figures strongly here and elsewhere in the book. It is highly important if only because of the significance of coal for China and India and he calls for financial commitment to help fund thirty-plus new commercial-size plants in the next seven to eight years. His final plea is that rich countries deliver on their commitments to overseas development assistance, with extra costs of development arising from climate change.

He relates climate change policy to the current economic turbulence by pointing to two key lessons. First, that the financial crisis has been developing over 20 years and surely tells us that ignoring risk or postponing action is to store up trouble for the future. Second, to grow out of the recession we need a driver of growth which is genuinely productive and valuable. Low-carbon growth can easily be that driver.

The book is a mine of information and helpful explanation of how proposed policy measures can work. Stern has worked closely with politicians and policy makers and obviously has familiarity with how they work and think. That doesn’t mean he has been taken over by political calculations as to what is possible or not. Quite the contrary. He is firm on the primary responsibility of the rich nations to steer the world through to a co-operation on climate change which will both lower emissions and at the same time bring the benefits of development to the poorer nations. He is not afraid to sound a visionary note when he considers the good that can flow to all countries if we rise adequately to the challenge of a planet in peril. I was heartened as well as informed by his book.

Climate change is already having disproportionate effects on the populations of many poor developing countries, a situation which will only get worse as the global temperature rises. Such countries do not have the resources to develop the adaptation measures they are going to need. Nicholas Stern devoted considerable attention to this question in

Climate change is already having disproportionate effects on the populations of many poor developing countries, a situation which will only get worse as the global temperature rises. Such countries do not have the resources to develop the adaptation measures they are going to need. Nicholas Stern devoted considerable attention to this question in