Australian scientist and coral reef expert John Veron reckons there’s a “great big gorilla in the cupboard†— advancing ocean acidification. It cleans out reefs, leaving them “horrible places – dead, empty, slime-covered.†He paints this grim picture in a lecture given to the Royal Society in London last month. It’s available on line and I have just watched it – twice. His seriousness and the weight of his concern are deeply impressive. Veron warned that his talk would not be a happy one. Usually his talks on coral are fun. This one wouldn’t be, but “I’ve never given a more important talk in my life.†It was highly focused and informative, accompanied throughout by a range of illuminating pictures and graphs. I watched it carefully, anxious to fully understand its import, and have pulled out a rough summary of some of his major points.  Â

Australian scientist and coral reef expert John Veron reckons there’s a “great big gorilla in the cupboard†— advancing ocean acidification. It cleans out reefs, leaving them “horrible places – dead, empty, slime-covered.†He paints this grim picture in a lecture given to the Royal Society in London last month. It’s available on line and I have just watched it – twice. His seriousness and the weight of his concern are deeply impressive. Veron warned that his talk would not be a happy one. Usually his talks on coral are fun. This one wouldn’t be, but “I’ve never given a more important talk in my life.†It was highly focused and informative, accompanied throughout by a range of illuminating pictures and graphs. I watched it carefully, anxious to fully understand its import, and have pulled out a rough summary of some of his major points.  Â

Tag: ocean acidification

A deep sigh of relief…

Elizabeth Kolbert recently interviewed Jane Lubchenco (pictured), appointed by President Obama as head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Kolbert comments that when Lubchenco was appointed the reaction among climate scientists was an almost audible sigh of relief. During the Bush administration the work of NOAA staff was frequently ignored or even suppressed, and Lubchenco’s appointment was seen as a sign of the new administration’s resolve to finally take NOAA’s work seriously.

Elizabeth Kolbert recently interviewed Jane Lubchenco (pictured), appointed by President Obama as head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Kolbert comments that when Lubchenco was appointed the reaction among climate scientists was an almost audible sigh of relief. During the Bush administration the work of NOAA staff was frequently ignored or even suppressed, and Lubchenco’s appointment was seen as a sign of the new administration’s resolve to finally take NOAA’s work seriously.

Copenhagen 2: dangers ahead

The second section of the Copenhagen synthesis report, Social and Environmental Disruption, discusses the dangers of climate change relating to society and the environment, noting that scientific research provides a wealth of relevant information which is not receiving the attention one might expect.  Â

The second section of the Copenhagen synthesis report, Social and Environmental Disruption, discusses the dangers of climate change relating to society and the environment, noting that scientific research provides a wealth of relevant information which is not receiving the attention one might expect.  Â

Considerable support has developed for containing the rise in global temperature to a maximum of 2 degrees centigrade above pre-industrial levels, often referred to as the 2 degrees guardrail. The report however indicates that even at temperature rises less than 2 degrees impacts can be significant, though some societies could cope through pro-active adaptation strategies. Beyond 2 degrees the possibilities for adaptation of societies and ecosystems rapidly decline, with an increasing risk of social disruption through health impacts, water shortages and food insecurity.

What’s a few tears to the ocean?

New Zealand could be amongst the first places in the world to feel the effects of ocean acidification, according to a new “emerging issues” paper released today by the Royal Society of New Zealand. Surrounded by cold oceans which absorb CO2 faster than warm waters, and with a $300 million shellfish industry based on mussels, oysters, scallops and paua, NZ is vulnerable to disruptions in the carbonate chemistry used by these animals to build their shells, but the risks cannot be quantified at present.

New Zealand could be amongst the first places in the world to feel the effects of ocean acidification, according to a new “emerging issues” paper released today by the Royal Society of New Zealand. Surrounded by cold oceans which absorb CO2 faster than warm waters, and with a $300 million shellfish industry based on mussels, oysters, scallops and paua, NZ is vulnerable to disruptions in the carbonate chemistry used by these animals to build their shells, but the risks cannot be quantified at present.

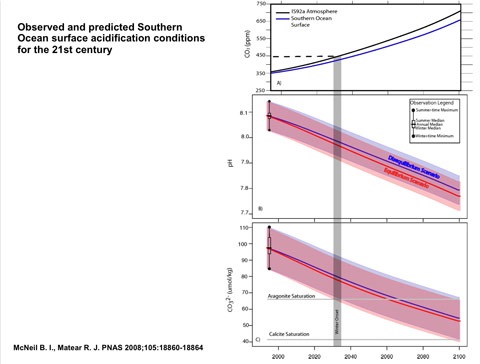

At a briefing to launch the paper, Professor Keith Hunter of the University of Otago pointed to recent work which suggests that for creatures that build their skeletons from a form of calcium carbonate called aragonite, the Southern Ocean could be reaching a critical point as early as the 2030s, as this slide shows:

The magic number is 450 ppm: at that point low pH waters in winter could begin to make it difficult for creatures to build aragonite skeletons or shells. How this might cascade through marine ecosystems is unknown, because the impact on different species can vary through their lifecycle and by season. Some species are also known to be able to adapt. Sydney rock oysters, for example, have been bred to withstand more acid conditions, but it’s not known whether this sort of work would be possible with mussels and other shellfish.

Work on ocean acidification is beginning to provide a valuable and independent line of evidence supporting the need to shoot for stabilisation of atmospheric CO2 at low levels. It may also point to problems with emissions trajectories that are allowed to “overshoot” the desired target: if oceanic CO2 uptake does produce a biologically critical response, exceeding that point might be very bad news for oceanic ecosystems.

The new Royal Society paper gives a very useful overview of what we currently know about ocean acidification and its potential to impact New Zealand ecosystems and marine farming operations. The RS is also organising a workshop in September to discuss the issue.

[Dimmer]

The Long Thaw

The legacy of our release of fossil fuel CO2 to the atmosphere will be long-lasting. It will affect the Earth’s climate for millenia. We are becoming players in geologic time. That is the conclusion that climatologist David Archer shares with a general audience in his newly published book The Long Thaw: How Humans Are Changing the Next 100,000 Years of Earth’s Climate.

The author is a professor in the Department of The Geophysical Sciences at the University of Chicago and a contributing editor at Real Climate. His book is relaxed in style, almost conversational sometimes, repetitive on occasion, but nevertheless closely focused and packed with instructive detail. It was a pleasure for a non-scientist like me to read. He seems to understand how to illuminate processes for the general reader. For example, his chapter on the distribution of carbon in the atmosphere, the land and the ocean, and his explanation of the interactions between them in the carbon cycle, provided angles and information that pulled together satisfyingly the bits and pieces of my hesitant understanding. Similarly what he writes about the acidifying of the ocean by CO2 and the part calcium carbonate plays in slowly neutralising its effect is a model of lucidity.

The book’s structure is simple. There are three sections. The first describes the situation we are in right now – meaning the 20th and 21st centuries. The second section is about the past, investigated as a forecast for the future. The final section looks into the deep future.

Archer produces no surprises about our current situation. The basic physics of the greenhouse effect – that gases in the atmosphere that absorb infrared radiation could eventually warm up the surface of the earth – was described in 1827 by the French mathematician Fourier. Then in 1896 Swedish chemist Arrhenius estimated the amount of warming that the Earth would undergo on average from a doubling of the atmospheric CO2 concentration – what we now call the climate sensitivity. Such work sets the scene for the climate science which has exploded in the past few decades as global warming grew from a prediction into an observation. He describes many aspects of our current understanding of global warming, with several particularly helpful sequences, such as that on the relative strengths of four external agents of climate change called climate forcings – greenhouse gases, sulfur from burning coal, volcanic eruptions, changes in intensity of the sun. The warming that is occurring cannot be explained by natural forcings. Looking ahead in the present century he is very aware that sea level rise by 2100 may well be higher than predicted by the IPCC, as it begins to appear that the ice models used to forecast may be too sluggish to predict the behaviour of real ice.

In the second section he moves steadily back in time, starting with the last 100,000 years where the abruptness of some of the changes detected leads him to reflect that the IPCC forecast of a smooth rise in temperature from 0.5 degrees excess warmth today to about 3.0 degrees excess warmth in 2100 represents a best-case scenario in that it contains no unfortunate surprises. He then treats the longer-term glacial climate cycles through the last 650,000 years, paying attention to orbital forcing and to the ups and downs of atmospheric CO2 through the cycles. He envisages the ice sheets and CO2“entwined in a feedback loop of cause and effect, like two figure skaters twirling and throwing each other around on the rink.” His final step back is to the hothouse world of 50 million years ago and beyond that to transitions between hothouse and ice age climates over 500 million years. He selects the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum event (recently discussed on Hot Topic) as an analogue for the global warming future.

The third section looks at that future. In discussing the land’s and ocean’s ability to take up carbon being released from fossil fuels he considers it likely that there are limits to that process which will mean that a significant fraction of fossil fuel CO2 will remain in the atmosphere for millenia into the future. There are calming effects from the carbon cycle, but there can also be opposite effects as seems likely to have been the case at times in the past. Hopefully large scale methane hydrate release won’t be a large part of such feedbacks, but if the ocean gets warm enough it is possible and could double the long-term climate impact of global warming.

For now the carbon cycle is responding to the CO2 increase by inhaling the gas into the ocean and high-latitude land surface, damping down the warming effect. But on the timescale of centuries and longer the lesson from the past is that this situation could reverse itself, and the warming planet could cause the natural carbon cycle to exhale CO2, amplifying the human-induced climate changes.

The clearest long-term impact of fossil-fuel CO2 release is on sea level rise. The book has a restrained chapter on this, but there is no escaping what will happen if the ice sheets melt. “We have the capacity to ultimately sacrifice the land under our feet.“

Have we averted an ice age? Archer discusses this possibility, but finds the evidence uncertain. He would in any case not put such a possibility forward as an argument in favour of CO2 emissions. All it means is that natural cooling driven by orbital variation is unlikely to save us from global warming – at this stage the much greater danger. Incidentally he mentions Ruddiman’s book Plows, Plagues, and Petroleum briefly and appreciatively in this section, but gives reasons for doubting its conclusions. (The book was reviewed on Hot Topic recently.)

In his epilogue on economics and ethics, where he ponders whether we are likely to turn away from the path we are currently on, he offers a comparison with slavery, another ethical issue: “Ultimately it didn’t matter whether it was economically beneficial or costly to give up. It was simply wrong.”

James Hansen describes the book as the best about carbon dioxide and climate change that he has read. “David Archer knows what he is talking about.” To which I would add that he also knows how to explain it clearly to anyone prepared to give him reasonable attention.