Severe risks to human health will accompany the disturbed global climate which comes with global warming. We have only to consider the consequences of the heat waves, the flooding, the African droughts, of recent times to be alerted to that. Our experiences of climate change in New Zealand are unlikely to reach such extreme levels, but we would be wise to think and prepare ahead for the kind of human health hazards we may expect to encounter. Chapter 8 in Climate Change Adaptation in New Zealand (pdf download) is an attempt to sketch out measures we might prepare to take. Four of the five writers are from the Department of Public Health at the University of Otago and one from Victoria University.

Severe risks to human health will accompany the disturbed global climate which comes with global warming. We have only to consider the consequences of the heat waves, the flooding, the African droughts, of recent times to be alerted to that. Our experiences of climate change in New Zealand are unlikely to reach such extreme levels, but we would be wise to think and prepare ahead for the kind of human health hazards we may expect to encounter. Chapter 8 in Climate Change Adaptation in New Zealand (pdf download) is an attempt to sketch out measures we might prepare to take. Four of the five writers are from the Department of Public Health at the University of Otago and one from Victoria University.

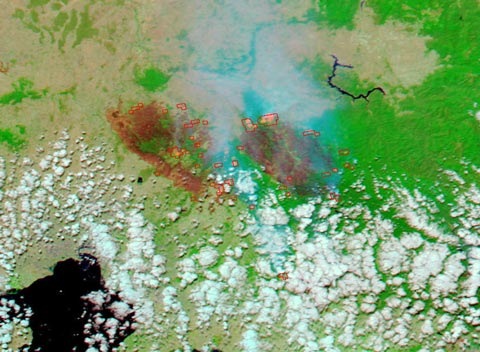

The paper rehearses some of the widespread major impacts which will affect human health globally. Higher maximum temperature will lead to increased heat-related deaths and illnesses and contribute to an extended range of some pest and disease vectors. Droughts and forest fires will increase in severity and frequency. More intense rainfall will lead to slope instability, flooding and contaminated water supplies. More intense large-scale cyclones increase the risk of infectious disease epidemics (e.g. via damaging water supplies and sewerage systems) and the erosion of low-lying and coastal land through storm surges. Indirect effects include economic instability, loss of livelihoods and forced migrations.

We have early indications of what the changes are likely to be, and it’s important to be ready with a range of policies to address them rather than wait and react as they occur. Prevention is better than cure. New Zealand may not experience the extremes which will be felt in some parts of the world, but there is much that would wisely be given attention.

One eventuality for which we need to be prepared, and which the article highlights, is the possibility of New Zealand becoming a lifeboat to those living in more vulnerable Pacific countries who are displaced by the impacts of climate change. Particularly is this to be expected if a high carbon scenario prevails, as increasingly seems on the cards. Families forced to leave their island homes are likely to form a pattern of chain migration to New Zealand. Unless, under such circumstances, we recognise the need to build extended-family houses or generally increase the supply of low-income family housing to accommodate these immigrants, we are likely to see an increase in overcrowding in state houses and other low-income housing. This could mean a dramatic increase in the risk of a number of infectious diseases.

Infectious diseases are likely to become more prominent with climate change. Warmer temperatures and increased rainfall variability can increase food-borne and water-borne diseases. Vector organisms such as mosquitoes, ticks and sandflies are strongly affected by temperature levels and fluctuations. Hopefully the risk of dengue in New Zealand may remain below the temperature threshold for local transmission, but there is likely to be a potential for outbreaks of Ross River virus infection.

Flooding is another aspect of climate change to which the paper gives some attention. Adaptive responses, such as health and housing protection and provision during and after extreme events, should not increase health inequalities. The spectre of New Orleans is invoked to illustrate this. The possible need for relocation of towns and even parts of cities looms in some areas of the world. In New Zealand the sustainability of Kaeo, flooded several times in recent years, has been questioned. But given low income levels and less disposable income for private insurance in such towns, government assistance is likely to be needed to facilitate relocation.

Other possible health impacts in New Zealand are touched on, including the effects of heat stress on outdoor workers, the exacerbation of asthma symptoms from increased amounts of allergen-producing pollens, the possibility of water charging by local authorities depriving lower income households of access sufficient to ensure general cleanliness.

Isolation and poor access to services puts people at increased risk. Severe mental health problems are identified as a likely risk in rural communities suffering the effects of extreme weather events. Such vulnerability extends also to low-income populations living in socio-economically disadvantaged, residentially segregated areas where there is less public transport and fewer people who own or have access to cars. The paper makes a good deal of the need for adaptation policies to be equitable and fair and inclusive.

Individual adaptive action can be hampered by lack of understanding, but may be attractive when there are co-benefits. An example is walking, cycling and taking public transport which can be presented as less a sacrifice of time and convenience and more an opportunity to socialise, keep fit, and do one’s bit towards a smaller carbon footprint.

At the community level the paper points to the critical role of local government. The progressive modification of urban form will be an important part of adaptation. Intensifying housing, for example, can reduce the vulnerability of dispersed communities and at the same time help build social capital that links together different social and ethnic groups, while reducing car dependence and energy use. Health and environmental benefits can flow from this.

New Zealand cities have little high density housing and a good many large sprawling suburbs. Some attention is beginning to be given to climate change adaptation issues. The paper focuses on dealing with storm-water run-off and urban heat island effects. Trees, parks and roof-top gardens and reduction of roads and parking lots are among the measures to reduce heat effects. Passive cooling of buildings through good design and the painting white of some surfaces also works to this end. Measures to slow storm water run-off, such as rooftop collection, replacement of hard surfaces by porous paving and well-vegetated low-lying areas can reduce risks. Steps to prevent the incursion of storm water into sewerage systems are important.

Enhanced social networks in cities and other local communities will be needed to provide closer monitoring of, and assistance to, vulnerable people and populations. Living behind locked doors with little neighbourhood contact is not a good preparation for the stresses climate change will bring.

Some needed changes require central government involvement. The paper mentions such matters as retrofitting houses to make them more energy efficient, raising standards in the Building Code, providing social housing. But it also notes that the government record to date shows little sign of advance, and that lack of government progress on mitigation makes adaptation more difficult.

Local government in New Zealand is already expected to take climate change into consideration in its planning, and is provided with useful information by the Ministry for the Environment for doing so. The kind of thinking about health impacts expressed in this paper fits well into the overall intention to “avoid or limit adverse consequences and enable future generations to provide for their needs, safety and well-being.” Some of it overlaps with measures already recommended to councils. All of it is worth taking up in the discussions and reports that mark local government. Central government seems trickier ground, more subject to the vagaries of ministers and politics, but one hopes that the good sense represented in papers such as this makes its way there too.

Somehow Kevin Rudd’s climate change

Somehow Kevin Rudd’s climate change  NZ Incorporated has moved from a Kyoto deficit to a surplus, according to the

NZ Incorporated has moved from a Kyoto deficit to a surplus, according to the  The Emissions Trading Scheme Review committee has released the

The Emissions Trading Scheme Review committee has released the