This guest post is by Jonathan Musther, who has just published an amazing series of highly detailed maps projecting future sea level rise scenarios onto the New Zealand coastline. If you live within cooee of the sea, you need to explore his maps. Below he explains why he embarked on the project.

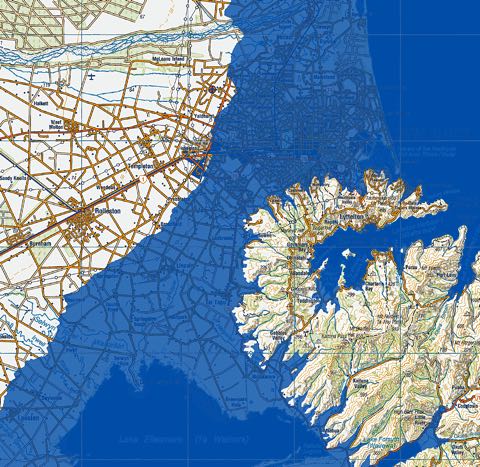

The effect of 10m sea level rise on Christchurch: say goodbye to St Albans, prepare to paddle in the CBD. Full map here.

For humans, sea-level rise will almost certainly be the most directly observable effect of climate change, and specifically of global warming. As the climate changes, many of the effects will be subtle, or if not subtle, they will at least be very complex. Summers may be warmer, or cooler; we may experience more rain at some times of year, and less at others; tropical storms may increase and they may be sustained further from the equator, but all of these changes are complex, and not necessarily obvious against the background complexity of any climate system. In contrast, there is something obvious and unstoppable about sea-level rise, there is no question that it will send anyone in its path running for the hills.

For some time I have been involved in searching for land appropriate for specific uses such as arable farming, water catchment, and off-grid living. When searching for land in this way, there are many, many criteria to consider, and of course one of these is potential future sea-level. Using GIS (Geographical Information System) software, and elevation models of the New Zealand landscape, it is possible to visualise sea-level rise, and select sites accordingly. Naturally, the next question is what sea-level rise to consider. It is possible to place an upper-limit on sea-level rise – after all, there’s only a finite amount of ice that could melt – but beyond that, we’re limited to informed guesswork.

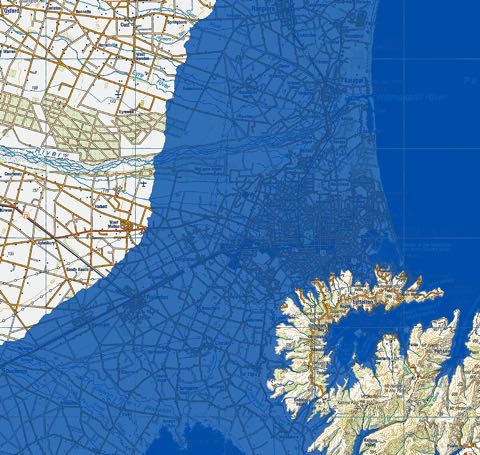

25m sea level rise: a sunken city and Banks Island. Full map here.

What is the maximum possible sea-level rise? It depends who you ask. Many sources place the maximum potential sea-level rise at around 60-64 metres, but these figures are rarely referenced, and don’t concur with the latest research. Other sources place the figure at around 80-81.5 metres, and while this appears to be well referenced and researched, it is based on work that is somewhat out of date. The best estimates I’ve been able to locate, based on recent measurements (and lots of them) are around 70 metres, but quite what the margin of error is remains uncertain. Of course, when considering future sea-level, we must remember that here in the South Pacific, we will likely experience increased numbers of more powerful tropical storms, with associated storm surges.

At 80m, West Melton is a seaside township. Full map here.

The maps I created showing sea-level rise for the whole of New Zealand depict rises of 10, 25 and 80 metres. I have certainly received criticism for not focussing on more modest sea-level rises (e.g. 1 or 2 metres), but there are some good reasons for this: firstly, the resolution of the elevation models of New Zealand do not allow accurate predictions of such small rises. Secondly, larger sea-level rises pose a huge threat, and are therefore worth considering. I made a point of avoiding time frame predictions when producing the sea-level rise maps, partly because the time frame is largely irrelevant (if 80% of our homes are flooded, it’s bad news, no matter when) and partly because the range of expert estimates is huge. Study after study shows that we have underestimated ice-sheet instability, and it is almost universally accepted that large sea-level rise will be a consequence. Unfortunately, most studies place this sea-level rise at some unspecified time in the future – when, we’re not sure, but it’s far enough away that we needn’t worry…

So is a 10 or 25 metre sea-level rise likely? Unfortunately, the broad answer is yes. The Greenland, West and East Antarctic ice sheets are showing growing instability, and many researchers agree that they may have past a ‘point of no return’. Remember, the Greenland ice sheet alone, if completely melted, would lead to approximately a 7 m rise in global sea-level. Of course, we return to the issue of when this is likely to happen, and on that, the jury is out.

I firmly believe that to be good scientists, we must investigate the possibility of large sea-level rise, and its consequences. The time frame is unclear, the absolute rise is also unclear, but there really is something unstoppable about rising oceans. We are now well outside the sphere of collective human experience and expertise, and we should be very careful to prepare, as best we can, for a range of scenarios.

Towards the end of a recent Yale Environment 360

Towards the end of a recent Yale Environment 360

You must be logged in to post a comment.