There’s record heat in Australia and deep snow in England (with more to come, say Met men), and it’s all consistent with continuing global warming. Over at Wellington’s leading public transport blog, this is enough to inspire a remarkably ill-informed diatribe:

There’s record heat in Australia and deep snow in England (with more to come, say Met men), and it’s all consistent with continuing global warming. Over at Wellington’s leading public transport blog, this is enough to inspire a remarkably ill-informed diatribe:

Following the news as I do, it was delicious today to see the global warmers claiming Melbourne’s summer heatwave was proof of Pope Gore’s alarmism, while ignoring the inconvenient truth that the heaviest snowfalls in decades are falling in London, Paris and much of the north-east of North America.

The really inconvenient truth, of course, is that both weather events neatly demonstrate some of the impacts of global warming and the changes in climate that result.

I haven’t lived through an Australian heatwave, but Professor Barry Brook of the University of Adelaide, who blogs about climate issues at the very good BraveNewClimate, has been our “man on the spot” for the current heat extremes. In a recent post he looked in detail at the relationship between the heatwave and climate change — and found a strong link. His article is worth reading in full, but one fact really strikes home. Adelaide has had two extreme heatwaves in one year. A long heatwave in March last year was estimated to be a 1 in 3,000 year event (assuming a static climate), and yet within a year the city has experienced another extremely unusual event. Here’s Brook’s comment:

So, in Adelaide we have two freakishly rare extreme events happening with a 10 month period. How likely is that? Well, if the events are totally independent, we’d expect the joint likelihood of two such heatwaves (of 0.25% probability per year [the 2009 event] and 0.033% per year [2008 event], respectively), occurring within the same 12 month period, to happen about once every 1,200,000 years.

It’s therefore very likely that the two events share a common cause — a shift in climate: an underlying warming. To illustrate the point, Brook points to this chart from the IPCC’s Fourth Report:

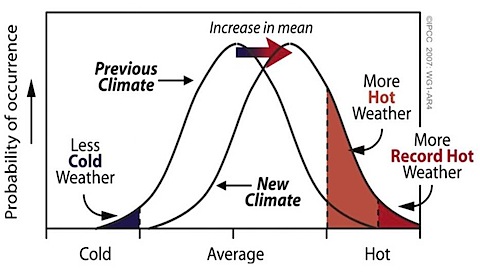

The two bell-shaped curves represent how often different temperatures are likely to occur . Obviously, most of the time the temperature is likely to be near average — up at the top of the curve. Hot and cold temperature anomalies are to be found in the “tails” of the curve on either side. If the climate warms, the whole curve moves to the right, and so you get both more hot weather, and more record hot weather. At the other end of the curve, you get fewer cold weather events, and the cold weather that happens is less cold than it was before. And that’s what’s happening in Britain.

London last had snow as extensive as this in 1991. I was living in London at the time and remember the perfect deep powder that lasted a few days, long enough to take the kids skiing and sledging in Richmond Park (although by the time we got there through the traffic jams of keen snow bunnies it looked pretty much like this BBC News video — no powder in sight). At that time, the snow was unusual but far from unprecedented. I can recall several similar events in the 1980s (some also involving skiing in parks). The Met Service has crunched the numbers and reckons (according to the UK Telegraph) that snow on this scale happened about once every five years in Victorian Britain, and in that BBC report Sir Brian Hoskins from Imperial College draws a comparison with 1963, when similar weather patterns delivered not only much colder air from the continent, but also a lot more snow. It now looks as though snow in London has become much less likely than hitherto — a 1 in 20 year event, according to the Met Service.

The bottom line: as the climate shifts towards more warmth, you might not notice the small change around the average, but the changes in the extremes — more hot weather, new hot weather records, balanced by less cold weather, and cold weather that’s less cold — will be much more obvious. [See also this recent study on European weather extremes]

Meanwhile, our blinkered blogger gets his facts wrong, and proceeds to fall off his trolley bus:

The warmers will desperately argue to the contrary and say why a hugely cold year worldwide proves the opposite of the facts. Hey! They may be right but their claims are a religious belief, not science.

It would be nice if for once, when it comes to climate issues, he would actually read the science — not just the sceptic rump — before committing his thoughts to the net.

But I’m not holding my breath.

I notice that amongst the tags at the bottom you have included the tag “cranks”. You might say that but I couldn’t possibly comment.

So it’s been a hugely cold year worldwide? I didn’t know that!

Yes, that was a remarkable revelation — there was me thinking 2008 was the ninth warmest in the record. It’s obviously amazing what you can learn by watching the buses go by…

Just a quibble with Barry Brooks’s calculation:

Given the tendency for persistence in the climate system, one would not necessarily expect the events to be totally independent, so the estimated joint likelihood is too low.

PS: I agree with everything m.hadfield said. He’s a sterling fellow!

As it happens, I think Barry’s revised his calculation in the comments to his post — to 1 in 150,000, if I recall correctly. Still a very long way out into the “tail” of the distribution…

I’m not sure about this Hadfield bloke: his server’s called “squid”. Mind you, that’s preferable (with sweet chilli sauce) to the readers who arrive from Landcare research, where some disgruntled IT bloke has dropped an “r”: poxy.landcare.cri.nz.

I see in his latest rant Poneke casts all us Religious Warmists into Hell.

http://poneke.wordpress.com/2009/02/11/fire-3/#comments

I couldn’t believe that post: he’s not just jumped any old shark, he’s gone for a big fat whale shark… Contrast P’s diatribe with the first comment on my Fires post. The similarities are too obvious.