Adapting to Climate Change is a reassuring sounding title, but the content of this book makes it clear that there will be nothing straightforward or easy as human communities try to ready themselves for the coming climate crisis. Editors Neil Adger, Irene Lorenzoni and Karen O’Brien have been doing on research in the area for a number of years and worked closely together in the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report on adaptation. They convened a conference in 2008 at the Royal Geographical Society in London and the resulting papers are the basis of this book, now published in a paperback edition.

Author: Bryan Walker

The road to ruin

Kevin Anderson from the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change at the University of Manchester has been sounding alarms about the inadequate rate of reduction of greenhouse gas emissions for some years now. He’s done it again in a sobering paper written with colleague Alice Bows and recently published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (free access).

A Guardian article this week indicates some of the gist of the paper. Anderson points out that that policy advisers and policy makers are working on the basis of naïve and inappropriate assumptions which simply don’t obtain in reality. Growth rates in emissions are actually much higher than those used by most Integrated assessment models (IAMs) employed by researchers today, where climate change data is integrated with economic data. Emission peaks, even on an optimistic reckoning are not likely before 2020-2030 whereas most IAMs estimate 2010-2016. The IAMs also assume untested geoengineering, and a high penetration of nuclear power alongside untested ‘carbon capture and storage’ technologies.

Anderson’s calculations have shown that, if we want to aim for a high chance of not exceeding a 2 degree increase in global temperature by the end of the century, our energy emissions need to be cut by nearer 10% annually rather than the 2–4% that economists say is possible with a growing economy.

The models are producing politically palatable results. However, the reality is far more depressing and unfortunately many scientists are too afraid to stand up and say so for fear of being ridiculed.

“Our job is not to be liked but to give a raw and dispassionate assessment of the scale of the challenge faced by the global community.”

Because policy makers are living with false hopes they are not engaging with the sweeping changes necessary for industrialised nations to drastically reduce their emissions.

“This requires radical changes in behaviour, particularly from those of us with very high energy consumption. But as long as the scientists continue to spread the message that we will be ok if we all make a few small changes, then climate change will never be on top of the policy agenda and we will fail to meet our international commitments to avoid a 2 degree rise.”

Climate change is not a problem to be addressed in the future, but a cumulative problem that needs to be tackled now. And this can only be done if researchers use realistic data and report brutally honest results, no matter how disturbing or depressing.

To turn to the paper. It points out that though the Copenhagen Accord reiterated the commitment to hold the increase in global temperature below 2 degrees, it focused on global emission peak dates and longer-term reduction targets instead of facing up to cumulative emission budgets. That focus belies seriously the scale and scope of mitigation necessary. There was also lack of attention to the pivotal importance of emissions from non-Annex 1 (developing) nations in shaping available space for Annex 1 (developed countries) emission pathways. The paper provides a cumulative emissions framing to show what rapid emissions growth in nations such as China and India mean for mitigation rates elsewhere.

The consequence of focusing on end-point targets rather than facing up to emission pathways is that there is now little to no chance of maintaining the global mean surface temperature at or below 2 degrees.

“Although the language of many high-level statements on climate change supports unequivocally the importance of not exceeding 2 degrees, the accompanying policies or absence of policies demonstrate a pivotal disjuncture between high level aspirations and the policy reality.”

In essence we are putting off what must be faced up to now:

“In general there remains a common view that underperformance in relation to emissions now can be compensated with increased emission reductions in the future. Although for some environmental concerns delaying action may be a legitimate policy response, in relation to climate change it suggests the scale of current emissions and their relationship to the cumulative nature of the issue is not adequately understood.”

We are also relying on an outdated understanding of the likely severity of the impacts of a 2 degree rise in global temperature:

“…it is reasonable to assume…that 2 degrees now represents a threshold, not between acceptable and dangerous climate change, but between dangerous and ‘extremely dangerous’ climate change; in which case the importance of low probabilities of exceeding 2 degrees increases substantially.”

In relation to economic growth, the paper observes that if only a 2-4% level of emission reductions is compatible with economic growth, then it appears that:

“…(extremely) dangerous climate change can only be avoided if economic growth is exchanged, at least temporarily, for a period of planned austerity within Annex 1 nations and a rapid transition away from fossil-fuelled development within non-Annex 1 nations.”

The paper’s judgement as to the reality underlying the political talk:

“Put bluntly, while the rhetoric of policy is to reduce emissions in line with avoiding dangerous climate change, most policy advice is to accept a high probability of extremely dangerous climate change rather than propose radical and immediate emission reductions.”

The reader won’t argue with the authors’ description of their assessment of the climate challenge as “stark and unremitting”.

But they deny any negative intention:

“However, this paper is not intended as a message of futility, but rather a bare and perhaps brutal assessment of where our ‘rose-tinted’ and well intentioned (though ultimately ineffective) approach to climate change has brought us. Real hope and opportunity, if it is to arise at all, will do so from a raw and dispassionate assessment of the scale of the challenge faced by the global community. This paper is intended as a small contribution to such a vision and future of hope”

Hot Topic readers may recall that Clive Hamilton’s book Requiem for a Species, reviewed here, drew on an earlier 2008 paper by Anderson and Bows and quotes Anderson at the 2009 Oxford conference where climate scientists looked at the implications of a 4 degree increase in global temperature: “The future looks impossible.” It’s a pretty slim hope that Anderson allows, but he’s right to puncture the false ones.

Europe looks to bolder targets

No doubt the New Zealand climate change minister will point out that the New Zealand’s emissions profile is different from that of the EU and that the exchanges about reduction targets that have been taking place in Europe in recent days therefore have little relevance for us. Nevertheless I have taken heart from reading about them in their own right, whether they have relevance to us or not, though I think they do have at least some.

No doubt the New Zealand climate change minister will point out that the New Zealand’s emissions profile is different from that of the EU and that the exchanges about reduction targets that have been taking place in Europe in recent days therefore have little relevance for us. Nevertheless I have taken heart from reading about them in their own right, whether they have relevance to us or not, though I think they do have at least some.

Currently the EU has a target of a 20% cut in emissions by 2020. The Guardian reported last week that the UK’s climate change secretary Chris Huhne (pictured) wants to see that target toughened to 30%. Gunther Oettinger, the EU’s energy commissioner, disagreed on the kind of cautious grounds that we are all too familiar with in New Zealand. “If we go alone to 30%, you will only have a faster process of de-industrialisation in Europe. We need industry in Europe, and industry means CO2 emissions.”

Lignite: dirty brown forbidden fruit

Two items during this week highlighted the continuing progress of Solid Energy’s intentions to develop the Southland lignite fields. I therefore provide this depressing update to two Hot Topic posts on the issue late last year. Don Elder (left), CEO of state-owned enterprise Solid Energy, appeared before the Commerce select committee during the week and announced that the proposed lignite developments will be worth billions. And it appears that this will be the case even if they don’t receive free carbon credits under the ETS, which they appear to nevertheless hope for. There was a slight acknowledgement that there were carbon footprint issues still to be resolved and some soothing suggestions, reported in the Otago Daily Times, that approaches such as mixing synthetic diesel with biofuels, carbon capture and storage, and planting trees, could reduce the net emissions. With a convenient fall-back – that the company could pay someone elsewhere in the world to do this for it. There is little evidence that carbon capture and storage will feature as anything more than talk in this scenario. The wildest extremity of the CCS option was touched on outside the committee when Elder spoke of the possibility of eventually piping carbon out to sea and pumping it into sea-floor oil or gas wells, after the Great South Basin has been developed.

Two items during this week highlighted the continuing progress of Solid Energy’s intentions to develop the Southland lignite fields. I therefore provide this depressing update to two Hot Topic posts on the issue late last year. Don Elder (left), CEO of state-owned enterprise Solid Energy, appeared before the Commerce select committee during the week and announced that the proposed lignite developments will be worth billions. And it appears that this will be the case even if they don’t receive free carbon credits under the ETS, which they appear to nevertheless hope for. There was a slight acknowledgement that there were carbon footprint issues still to be resolved and some soothing suggestions, reported in the Otago Daily Times, that approaches such as mixing synthetic diesel with biofuels, carbon capture and storage, and planting trees, could reduce the net emissions. With a convenient fall-back – that the company could pay someone elsewhere in the world to do this for it. There is little evidence that carbon capture and storage will feature as anything more than talk in this scenario. The wildest extremity of the CCS option was touched on outside the committee when Elder spoke of the possibility of eventually piping carbon out to sea and pumping it into sea-floor oil or gas wells, after the Great South Basin has been developed.

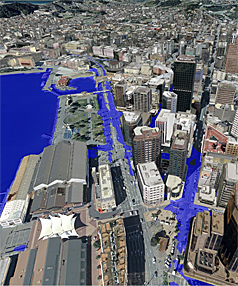

Here comes the flood

News today of interesting new research on the effect of rising sea levels on 180 US coastal cities by the century’s end. University of Arizona scientists will be publishing a paper this week in Climatic Change Letters which sees an average 9 per cent of the land within those cities threatened by 2100. The Gulf and southern Atlantic cities, Miami, New Orleans, Tampa, Fla., and Virginia Beach, Va. will be particularly hard hit, losing more than 10 per cent of their land area.

The research is the first analysis of vulnerability to sea-level rise that includes every U.S. coastal city in the contiguous states with a population of 50,000 or more. It takes the latest projections that the sea will rise by about 1 metre by the end of the century at current rates of greenhouse gas emissions and thereafter by a further metre per century. The researchers examined how much land area could be affected by 1 to 6 metres of sea level rise. At 3 metres, on average more than 20 per cent of land in those cities could be affected. Nine large cities, including Boston and New York, would have more than 10 per cent of their current land area threatened. By 6 metres about one-third of the land area in U.S. coastal cities could be affected.

The study has created digital maps to delineate the areas that could be affected at the various levels. The maps include all pieces of land that have a connection to the sea and exclude low-elevation areas that have no such connection. Rising seas do not just affect seafront property – water moves inland along channels, creeks, inlets and adjacent low-lying areas.

“Our work should help people plan with more certainty and to make decisions about what level of sea-level rise, and by implication, what level of global warming, is acceptable to their communities and neighbours,” said one of the co-authors.

An interesting notion, that of deciding how much sea level rise is acceptable. Shades of King Canute? It’s presumably the speaker’s way of pointing out that it may still be within our power to keep it manageable if we begin an urgent and drastic reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Or perhaps he’s hinting at a time where only relocation will serve. For the present some adaptation measures are now unavoidable and should be planned for, but hopefully the digital maps of this study will help convince people that mitigation is also essential. Not seemingly the Republican majority in the House which bizarrely rampages on as if human-caused climate change isn’t happening, let alone in need of mitigation.

I wonder how much similar mapping has been done in the case of New Zealand coastal cities. The Wellington City Council has gone so far as to consider a computer-generated graphic (pictured) which visualised the effect of a one metre rise in sea level on the city. Nelson has considered a commissioned report on climate change effects which warned that a 1 metre sea level rise would have water lapping at the airport. I don’t recall seeing anything which indicates that Auckland has seriously looked at the effect. Christchurch is planning for a 50 cm sea level rise this century with the recognition that it may be higher and presumably that means they are undertaking detailed consideration of vulnerable areas. Dunedin has had the benefit of some University of Otago modelling of a 1.5 metre sea level rise, reported here, with assurance from the new Carisbrook stadium that they’re 3.7 metres above mean sea level. I’ve written earlier on encouraging signs that local body government in New Zealand, at least in some areas, is facing up to the responsibilities for adaptation. In some cases this has meant taking on mitigation measures as an obvious consequence, though Environment Waikato’s Proposed Regional Policy Statement states that the Council’s role is to prepare for and adapt to the coming changes and that response in terms of actions to reduce climate change is primarily a central government rather than a local government role. I’ll be challenging that in my submission, since it seems to me that engaging people locally in mitigation effort is both possible and sensible, especially when they can see locally what the prospects will likely be without it.

The costs of coping with sea level rise look likely to be enormous. If in fact that is what future populations have to do they will look back in wonderment on the argument represented by such as our present government that we were unable to do anything deeply serious about mitigating the effects of climate change because we thought it might affect our economy adversely. True, we might have to acknowledge, there was a Stern review which pointed out that the costs facing you, our descendants, would dwarf the adjustments required of us, but somehow we couldn’t get over our hump to reduce your mountain.