A couple of days ago, NIWA published its climate summary for 2008 — a comprehensive overview of all the weather events that went together to make last year what it was. In general, 2008 was sunny and warm for New Zealand, but with many notable extreme weather events — a “rollercoaster” of a year, according to NIWA principal scientist Jim Renwick (who’s been a guest poster here). The Herald picked up on the rollercoaster reference, but Stuff latched on to something else Jim said:

A couple of days ago, NIWA published its climate summary for 2008 — a comprehensive overview of all the weather events that went together to make last year what it was. In general, 2008 was sunny and warm for New Zealand, but with many notable extreme weather events — a “rollercoaster” of a year, according to NIWA principal scientist Jim Renwick (who’s been a guest poster here). The Herald picked up on the rollercoaster reference, but Stuff latched on to something else Jim said:

[…] Renwick said the extremes could be a preview of how global climate change would affect New Zealand weather. “I am not saying 2008 was a result of climate change, but we should expect to see more years like that,” he said. “The idea of a sunny year, but with some pretty violent storms, is consistent with climate change. We should expect to see more of those rainfall extremes.”

The last time I looked at my weather records was last February. After musing on a heavy rain event, my comment then was “if you were to ask me what will Canterbury’s climate be like in 2030, I’d have to answer – just like this summer…” For our property in the Waipara Valley, 2007 was a dry year — only 496 mm of rain. 2008 was much wetter: 809 mm in the year, 10% over the average for the last 11 years, and the second wettest in my record. That’s been good news.

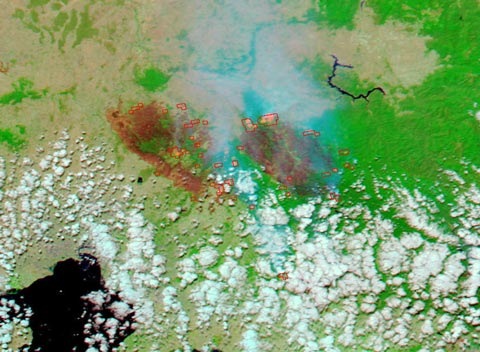

However, when I look back at the year, nearly 40% of that rain came in just three events — a big fall in February to break the dry spell, and then two big storms in late July and August, the latter severe enough to cause dramatic flooding in the region. Roughly 320 mm fell in those three events. I had to wash mud out of the garage three times, dig a drainage trench through the truffiere (truffles don’t like drowning), gullies eroded, the road slumped, and the Waipara River lowered its bed by half a metre in places.

Take away those big storms, and we had only 489 mm for the year — a dry year by my standards. Over the ten years up to 2008, we had a total of three comparable heavy rain events (Aug 2000, Jan 2002 and Sept 2003), and then like London buses, three came along at once.

What does this prove? Precisely nothing. I don’t have records going back far enough to know whether there’s any sort of statistical significance in 2008’s North Canterbury rainstorms. But… remember what Jim said earlier? The impact of global warming on the east coast of NZ is expected to increase the frequency of drought, but because warming also means more water vapour in the atmosphere — more “fuel” for weather — when rain does fall, it could come in floods. So if you were to ask me what Canterbury’s climate will be like in twenty year’s time, I’d have to answer – just like last year.

[Lemon Jelly]

Like this:

Like Loading...

As if to demonstrate to its peers what the art of good science communication is all about, MetService has just launched a blog. Bob McDavitt (left – great pic!) has posted an excellent article about autumn colour, describing the process that creates the yellows and reds that make our countryside reliably spectacular at this time of year. Erick Brenstrum has a post about a landslide on Stewart Island in 1810, and Ross Marsden has a note on regional cloudscapes. With a team of seven bloggers and a mandate to generate regular material, it promises to be a must visit site for anyone with weather watching tendencies. I hope they can also match some the excellent blog coverage The Weather Channel provides for big US weather events.

As if to demonstrate to its peers what the art of good science communication is all about, MetService has just launched a blog. Bob McDavitt (left – great pic!) has posted an excellent article about autumn colour, describing the process that creates the yellows and reds that make our countryside reliably spectacular at this time of year. Erick Brenstrum has a post about a landslide on Stewart Island in 1810, and Ross Marsden has a note on regional cloudscapes. With a team of seven bloggers and a mandate to generate regular material, it promises to be a must visit site for anyone with weather watching tendencies. I hope they can also match some the excellent blog coverage The Weather Channel provides for big US weather events.

There’s

There’s  A couple of days ago, NIWA published its

A couple of days ago, NIWA published its