A basket case, said Henry Kissinger of Bangladesh in 1974 after the civil war that liberated it from West Pakistan (the side he backed). Mark Hertsgaard in Hot (reviewed here) reports a rather different picture. I thought it worth dwelling longer on what he has to say about Bangladesh than was possible in the review because he shows the Bangladeshis as far from passive even in the face of what look like daunting odds, and because he underlines the case for assistance.

A basket case, said Henry Kissinger of Bangladesh in 1974 after the civil war that liberated it from West Pakistan (the side he backed). Mark Hertsgaard in Hot (reviewed here) reports a rather different picture. I thought it worth dwelling longer on what he has to say about Bangladesh than was possible in the review because he shows the Bangladeshis as far from passive even in the face of what look like daunting odds, and because he underlines the case for assistance.

Bangladesh’s ambassador to the US, in conversation with Hertsgaard, firmly refutes the Kissinger perspective.

We are now feeding ourselves, 140 million people. We have cut our population growth rate in half. All Bangladeshi children are immunized against major childhood diseases. Our economy has grown an average 5.5 percent a year over the last seventeen years. We are not a basket case at all.

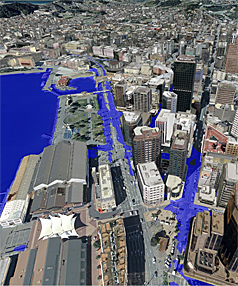

Hertsgaard acknowledges the advances, but recognises the threat they are under from climate change. The vulnerability of Bangladesh is well known. Two-thirds of the country stands less than sixteen feet above sea level. The three feet of sea level rise that Hertsgaard regards as unavoidable will displace an estimated 20 million Bangladeshis. Soil and water in coastal regions are already becoming too salty to deliver traditional rice yields. There’s plenty to suggest that Bangladesh appears doomed in the face of fifty more years of global warming. However, says Hertsgaard, spend some time inside the country and things look different.

He singles out the human factor. It counts for a lot in adapting to climate change. Bangladeshi biologist, Saleemul Huq, an influential advocate for the poor within the global climate change discussions, spoke to him of the resilience developed by people who have been dealing with floods and other disasters for centuries, “so they have greater capacity than rich people who are not used to facing catastrophe”. The months Huq spent researching among river communities of fishing families were an eye-opener for him, brought up in more favoured circumstances.

I got to know the poor as individuals, not as an abstraction. I saw they were extremely resilient and often ingenious at coping with the circumstances they faced.

Huq and others have subsequently developed an approach called Community-Based Adaptation in which experts on climate change impacts work together with poor communities in a dialogue of equals where local solutions which draw on the experience of local people can be devised.

Hertsgaard describes some of the adaptation measures he saw when visiting the Bangadeshi countryside. In one village a farmer had taken some simple steps to protect his family against the storm surges of cyclones. With NGO help he had elevated his mud and thatch house five feet above ground, on a mound of packed dirt with hard dirt steps leading up to the entrance. He explained to Hertsgaard that it had worked well and that during the last two cyclones they hadn’t had to go to the cyclone centre, which gets very crowded and short on food and water. Their own food, rice and fish, was kept dry during the floods in a basket made from tightly woven strands of bamboo, which floats.

In another village they relied on “floating gardens”. The villagers wove water hyacinth plants into a watertight mesh. The one Hertsgaard saw measured about fifteen feet long and ten feet wide and floated in one of the many ponds in the village. The mesh was covered with a few inches of topsoil, which was planted with vegetables. Since the structure floated it simply rose higher in flood inundation. The same village was also seeking to diversify its income sources by establishing, with NGO help, a tree nursery that grew mango and other fruit trees as well as medicinal herbs. Seedlings were sold in the local market.

These are very local and specific small measures, but the Bangladeshi government, in spite of its frequent dysfunctional bouts, has also been working on the wider picture for the past twenty years. With help from foreign donors it has invested $10 billion to bolster defences against floods, cyclones and drought. It has also pursued climate-focused agricultural research and is testing varieties of rice that could survive immersion in salt water for longer than two weeks. If successful that would help farmers cope with flash floods that mix sea and river water and will occur more frequently as sea levels rise. The government has developed an action plan to prepare for climate change on many fronts. But it will need money. Early estimates suggest that the first five years of work on the plan would cost about $5 billion. Some of this Bangladesh itself will pay for, but it can’t meet it all and it calls on the international community “to provide the resources needed to meet the additional costs of building climate resilience”.

Huq puts the obligation of the rich countries this way:

It is poor countries that are suffering the brunt of climate change, but it is the rich countries’ greenhouse gas emissions that caused this problem in the first place. If we follow the principle of “the polluter pays” they are obligated to pay damages. It is important to understand that this is not charity, like money given to poor countries for economic development. This is compensation.

US chief climate change negotiator Todd Stern told the Copenhagen climate summit that he “absolutely” rejected the suggestion that the US owes a “climate debt” to the rest of the world. Hertsgaard comments that as a lawyer himself Stern must surely know that in a court of law damages are damages, regardless of one’s intent.

I appreciated the attention Hertsgaard gave to the way Bangladesh is trying to face up to the challenges of climate change adaptation. The changes are real for them. They may be congruent with challenges they have long faced as part of their normal life, but they are mounting and threatening. Some of the adaptive measures he describes may turn out to have only been buying time as the sea continues its inexorable rise, but they are worthy of respect. They are also worthy of assistance.

The poor ask far less of life than we are accustomed to demand and the help they are seeking is not large by our standards. We would help them most, of course, by seriously taking in hand the task of drastically reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but while we continue to refuse this we at least owe them a measure of compensatory assistance.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Richard Alley’s book Earth: The Operators’ Manual, which I reviewed recently, was written as a companion to a PBS documentary of the same name. The documentary has recently screened in the US and is now available for viewing here. The broad themes are the same as those of the book. They’re not complicated: taking our energy from fossil fuels has caused climate change, but there are clean energy alternatives more than adequate to human needs and the sooner we move to deploy them the better.

Richard Alley’s book Earth: The Operators’ Manual, which I reviewed recently, was written as a companion to a PBS documentary of the same name. The documentary has recently screened in the US and is now available for viewing here. The broad themes are the same as those of the book. They’re not complicated: taking our energy from fossil fuels has caused climate change, but there are clean energy alternatives more than adequate to human needs and the sooner we move to deploy them the better.

Not infrequently when reading and reviewing a book I find myself wishing there was some way of lingering longer on what it has to say before the spotlight moves on.

Not infrequently when reading and reviewing a book I find myself wishing there was some way of lingering longer on what it has to say before the spotlight moves on.  A basket case, said Henry Kissinger of Bangladesh in 1974 after the civil war that liberated it from West Pakistan (the side he backed). Mark Hertsgaard in Hot (

A basket case, said Henry Kissinger of Bangladesh in 1974 after the civil war that liberated it from West Pakistan (the side he backed). Mark Hertsgaard in Hot (