This a guest post by Kevin Cudby, the author of From Smoke To Mirrors, reviewed earlier this week by Bryan.

I started researching my new book, From Smoke to Mirrors, back in 2007. I had been following alternative energy stories, and I was inundated with blogs and press releases from hucksters peddling silly ideas that would do nothing but separate investors from their savings.

So, in late 2007 I set out to document the strengths, weaknesses, and costs of all the options. I kept in mind that hydrocarbon liquid fuels (petrol, diesel, jet fuel, and fuel oil) underpin key elements of human civilisation, such as food production and distribution. Although the relative importance of cars, trucks, aircraft, and tractors might change over time, it will only be possible to eliminate liquid-fuel-related greenhouse emissions if we can find practical alternatives for every vehicle and machine. Forty percent of New Zealand’s liquid fuel is used on non-road applications, so it would be pointless to fix road transport and ignore agriculture, construction, aviation, and all the other non-road liquid fuel users.

My engineering background helped me sort the practical options from the vacuous nonsense. It had been a while since I’d worked with battery technology, and I enjoyed ferreting out detailed technical information about the latest rechargeable batteries, information their promoters would rather keep secret. I learned, for example, that battery-powered farm tractors would be about as practical as concrete helicopters. Then I moved on to hydrogen fuel cell vehicles—which, from the practical perspective, are looking pretty good. But hydrogen tractors are almost as impractical as battery-burners.

We know about practical processes for converting softwood chips into electricity, hydrogen, hydrocarbon fuels, and ethanol

It is clear that energy forestry is New Zealand’s most practical option for hydrogen, and for hydrocarbon fuels. New Zealand scientists knew about this possibility way back in the 1970s, though the technology for making trees into fuel was still being developed. Now, we know about practical processes for converting softwood chips into electricity, hydrogen, hydrocarbon fuels, and ethanol. No matter which technology New Zealand uses for road transport, our energy forests would occupy pretty-much the same amount of land. Researchers have calculated that the “energy profit” (or EROEI) of fuels made from wood chips will be better than that of our existing fossil fuels.

Perhaps the most exciting discovery, for me, was that radiata pine forests offer so many environmental side-benefits. I knew from personal observation that the native undergrowth in a 25-year-old radiata forest is far more luxuriant than the undergrowth in a 25-year-old stand of regenerating kanuka. But I am not a biologist, so I had to listen to the experts. I learned that converting steep low-quality grazing land into energy forests would improve biodiversity by creating habitat for a wide range of native species, from fungi to kiwis and falcons (the bird, that is). And I learned that foresters do not use fertiliser, and that third-generation radiata forests in the Central North Island are doing as well, or better, than the original plantings.

It seems New Zealand foresters have invented a biomass production process that can operate indefinitely. The technique has been thoroughly proven over many decades of real-world practice. We can share this expertise with other countries, which means Kiwi know-how can help knock a very large dent in anthropogenic greenhouse emissions.

There’s an excellent chance New Zealand will have the world’s cheapest renewable petrol and diesel

Even more exciting, there’s an excellent chance New Zealand will have the world’s cheapest renewable petrol and diesel. I’m guessing many New Zealanders will be very excited about that, especially considering what I learned about the future of conventional cars and trucks. Talking to overseas engineers, I learned about simple, practical engine and transmission systems capable of more than halving the fuel consumption of conventional road vehicles, without downsizing them, and without relying on battery hybrid systems.

So, although renewable petrol and diesel will be somewhat more expensive than today’s fuels, the improved efficiency of future vehicles will more than compensate.

We can be almost certain that sometime between now and 2030, the global economy will hit serious problems with the supply of liquid fuels. That is because fuel supplies will increasingly come from synthetic fuel factories. It can take up to six years to design, build, and fully commission a synthetic fuel factory, regardless of whether it makes climate-neutral fuel, or fossil fuel. Multi-national energy companies will be able to maximise their profits by delaying construction of synthetic fuel factories until prices begin to skyrocket. We know this will happen, but we cannot say exactly when it will start to affect global fuel prices. A growing number of analysts think it will happen before 2030, and the real pessimists think it will happen before 2020.

However, by 2040, if New Zealand gets stuck in and builds the necessary infrastructure, we can reasonably expect freight costs, and vehicle running costs, to consume a smaller fraction of the family budget than they do today.

There is no sign of any practical alternative for hydrocarbon liquid fuels for non-road applications. But these applications account for nearly half of New Zealand’s liquid fuel consumption.

So, while car and truck manufacturers are playing around with every technology that can turn a wheel, New Zealand should climate-neutralise its supply of essential, non-road fuels. This will keep us busy well into the 2020s. By then, thanks to advanced fuel injection and exhaust treatment systems, tailpipe emissions from conventional vehicles will be insignificant compared with pollution from tyre wear. All road vehicles have tyres, so environmental concerns will not influence our choice of cars and trucks. We’ll use whichever technology is the most practical.

From Smoke to Mirrors outlines a transition plan that takes account of these and other factors. I did not invent the transition plan. Associate Professor Susan Krumdieck did that, leaving it up to people like me to flesh it out and show why it is practical. Krumdieck proposed a direct attack on the problem’s fundamental origin. Fossil fuels cause greenhouse emissions, and greenhouse emissions cause climate change, so Krumdieck says we should simply ban fossil fuels. If you read From Smoke to Mirrors, you’ll see how simple and practical this would be.

New Zealand can do this. In fact, New Zealand should do this. We are a very small country, and if we cannot work together, how can we expect the rest of the world to do it?We need all our political parties to work out a multi-party agreement. This is about banning fossil fuels and developing the infrastructure to fully replace the billions of litres of fuel we’ll need by 2040. Left-right political questions, such as whether to build roads or railways, would be outside the scope of this agreement.

I’ve met young people who say: “We’re stuffed anyway, so I’m just gonna get as much as I can , while I can, and to hell with having kids.” That’s OK if there is no technical solution, or if the solution involves returning to medieval technology. But I’ve seen enough good technology to know the world will not go there. So, I hope my book will provide hope for those young people who have been led to believe there is no hope. My grandchildren’s generation will be the first to grow up knowing that we can solve this problem, because “From Smoke to Mirrors” makes the solutions readable and easily understood.

New Zealand can be self-sufficient for climate-neutral energy. Other countries can benefit from Kiwi expertise. This is a multi-decade project that could inspire every New Zealander. The question is whether our politicians are up to the challenge.

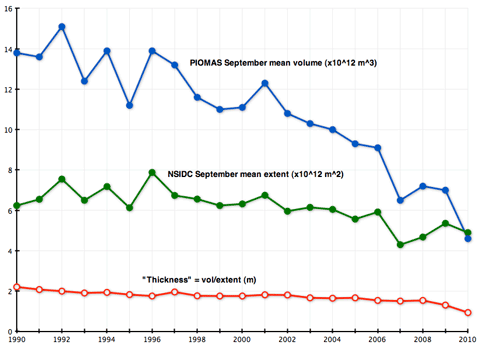

A few days ago I used a combination of Arctic sea ice volume data from the University of Washington’s PIOMAS model and NSIDC sea ice extent numbers to

A few days ago I used a combination of Arctic sea ice volume data from the University of Washington’s PIOMAS model and NSIDC sea ice extent numbers to

It appears that the crank pantheon has a new hero:

It appears that the crank pantheon has a new hero: