Paleoclimatologist Lonnie Thompson, distinguished university professor in the School of Earth Sciences at The Ohio State University, is well known and widely respected for his decades of work on ice caps and glaciers, especially in tropical and sub-tropical regions. In the past Thompson has let his research data and conclusions speak for him but he has this week caused something of a stir by voicing in a journal for social scientists and behaviour experts his concern at the grave risks we run in ignoring the evidence of climate change. Climate Change: The Evidence and Our Options is the title of his paper (available here) and it’s published in a special climate-change edition of The Behavior Analyst.

One hopes the paper has many readers. Its eighteen pages, a model of clarity, are highly accessible for the lay person.

Thompson opens by acknowledging that climatologists, like other scientists, tend to be a stolid group.

“We are not given to theatrical rantings about falling skies. Most of us are far more comfortable in our laboratories or gathering data in the field than we are giving interviews to journalists or speaking before Congressional committees.”

Why then, he asks, are climatologists speaking out about the dangers of global warming? Because virtually all of them are now convinced that global warming poses a clear and present danger to civilisation.

“There’s a clear pattern in the scientific evidence documenting that the earth is warming, that warming is due largely to human activity, that warming is causing important changes in climate, and that rapid and potentially catastrophic changes in the near future are very possible. This pattern emerges not, as is so often suggested, simply from computer simulations, but from the weight and balance of the empirical evidence as well.”

He explains the evidence from diverse data sources that points to relative stability in temperatures over the past 1000 years until the late twentieth century. Acknowledging that regional, seasonal and altitudinal variability can nevertheless make it difficult to convince the public and even scientists in other fields that global warming is occurring, he adds from his own area of expertise the evidence of melting ice.

The retreat of mountain glaciers is an early warning of climate change. He details the ice fields on the highest crater of Kilimanjaro which have lost 85% of their coverage since 1812. The Quelccaya ice cap in Peru, the largest tropical ice field on Earth, has lost 25% of its cover since 1978. Ice fields in the Himalayas that have long shown traces of the radioactive bomb tests in the 1950s and 1960s have since lost that signal as surface melting has removed the upper layers and thereby reduced the thickness of these glaciers. All of the glaciers in Alaska’s vast Brooks Range are retreating, as are 98 percent of those in southeastern Alaska. And 99 percent of glaciers in the Alps, 100 percent of those in Peru and 92 percent in the Andes of Chile are likewise retreating. Some telling photographic sequences illustrate the findings. It’s a pattern repeated around the world. To glacier retreat Thompson adds the loss of polar ice and sees global warming as the only plausible explanation.

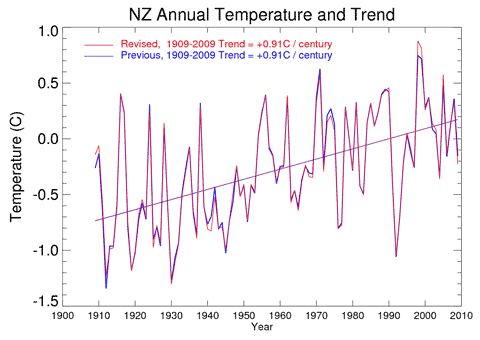

From there he moves to consideration of the natural forcers of climate change and the consensus among climatologists that the warming trend we have been experiencing for the past 100 years or so cannot be accounted for by any of the known natural forcers.

“The evidence is overwhelming that human activity is responsible for the rise in CO2, methane, and other greenhouse gas levels, and that the increase in these gases is fueling the rise in mean global temperature.”

The effects include sea level rise. He points out that if the Earth were to lose just 8% of its ice, the consequences for some coastal regions would be dramatic. The lower part of the Florida peninsula and much of Louisiana, including New Orleans, would be submerged, and low-lying cities, including London, New York, and Shanghai, would be endangered. Low-lying continental countries such as the Netherlands and Bangladesh are already battling flooding as never before and several small island states are facing imminent destruction. Other effects of warming Thompson touches on include the threats to glacier-fed fresh water sources on which populations in parts of the world depend and the increase in arid regions as the Hadley Cell expands.

Many of the models predicting future rises in temperature assume a linear rise in temperature. But in fact the rate of global temperature rise is accelerating, which is reflected in increases in the rate of ice melt, and in turn an increase in the rate of sea level rise.

“This [acceleration] means that our future may not be a steady, gradual change in the world’s climate, but an abrupt and devastating deterioration from which we cannot recover.”

At this point he discusses positive feedbacks, instancing forest fires, more dark areas opened through ice melt, and the release of CO2 and methane from melting tundra permafrost. He explains the possibility of tipping points as a result, with their ominous implications. But tipping points apart, if, as predicted, global temperature rises by another 3 degrees by the end of the century, the earth will be warmer than it has been in about 3 million years. Oceans were then about 25 metres higher than they are today.

What are our options for dealing with the crisis? Not prevention, for global warming is already with us. We are left with three: mitigate, adapt, suffer. Mitigation is the best option, but so far the US and other large emitters have done little more than talk about its importance. Many Americans don’t even accept the reality of global warming. Disinformation campaigns have been amazingly successful. Unless appropriate steps are taken we will be left with only adaptation and suffering. And the longer the delay the more unpleasant the adaptation and the greater the suffering will be. Those with the fewest resources for adaptation will suffer most.

It’s a grim picture. The information is not new. But it gains impetus when a leading scientist steps into the public arena and weaves his specialist contribution into the overall account in a way which leaves the reader with absolutely no doubt that the writer is convinced by the science and deeply alarmed at what it means for humanity. Like John Veron, whom I wrote about earlier this week, Thompson doesn’t allow scientific reticence to mute his message.

“Sooner or later, we will all deal with global warming. The only question is how much we will mitigate, adapt, and suffer.”

Like this:

Like Loading...