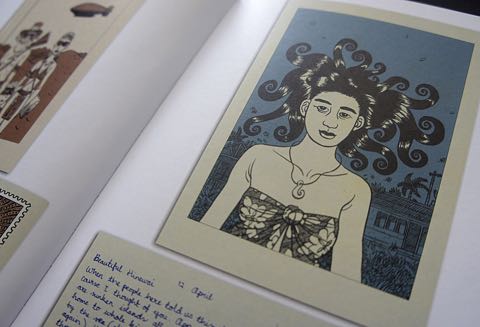

Scientists investigate how climate changes, politicians (should) decide what to do about it. Tough jobs. Artists have just as difficult a job: to comment on the reality and unreality they see in society’s responses to the climate threat, and by doing so motivate us to create a liveable future. In High Water, a new anthology of climate-inspired work by NZ comic artists, pulled together by Damon Keen and Faction Comics, that response ranges from the touching to the frightening, huge vistas seen through little frames — all presented in visually stunning stories drawn by NZ’s finest artists. The book kicks off with a superb little story by Dylan Horrocks, Dear Hinewai:

Scientists investigate how climate changes, politicians (should) decide what to do about it. Tough jobs. Artists have just as difficult a job: to comment on the reality and unreality they see in society’s responses to the climate threat, and by doing so motivate us to create a liveable future. In High Water, a new anthology of climate-inspired work by NZ comic artists, pulled together by Damon Keen and Faction Comics, that response ranges from the touching to the frightening, huge vistas seen through little frames — all presented in visually stunning stories drawn by NZ’s finest artists. The book kicks off with a superb little story by Dylan Horrocks, Dear Hinewai:

I’m a great fan of Dylan’s work ((That’s his image on the cover of The Aviator — see sidebar.)) — his latest, Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen is a real tour de force — and here he draws beautiful and bittersweet postcards from a future where New Zealanders are exploring a radically altered planet by airship ((Great minds, etc etc… 😉 )).

There is a lot of good stuff in High Water, but I have some personal favourites: Damon Keen’s The Lotus Eaters, which takes us on a trip from modern day Auckland through a grim future to the arcadia on the other side of our civilisation reminds me of the comics I grew up with (think Eagle), while Cory Mathis’ My Wife, The Mastodon looks at climate change through the eyes of ice age humans encountering neanderthals (and sabre tooth tigers). Chris Slane’s wonderful Dialogo di Galileo is a powerful poke at climate denial, with a great twist in the last frames.

There’s an introduction by Lucy Lawless, in which she hits the nail rather more effectively on the head than our Prime Minister:

These eleven incredible artists have not stinted in imagining the gravest outcomes of man-made climate change. Perhaps a visual warning will work better than a written one, that requires imagination from a recalcitrant mind. Gorgeous work!

She’s right, you know. We need all hands to the pumps if we’re going to deal with the inundation coming our way, and High Water is a most welcome contribution.

To see more images from the anthology, and to get more background on the inspiration behind it, see this interview with editor Damon Keen. High Water, featuring the work of Dylan Horrocks, Sarah Laing, Katie O’Neill, Cory Mathis, Christian Pearce, Ned Wedlock, Toby Morris, Damon Keen, Chris Slane, Ross Murray and Jonathan King is being launched this evening in Auckland. Best wishes to all who sail in her…

It is profoundly depressing to hear pundits and politicians talking about the prospects for economic growth with no reference to either equity or environmental constraints. In the case of New Zealand a “rock star” economy can apparently develop accompanied by dismaying levels of child poverty, excited expectations of new oil and gas discoveries which spell disaster for the climate, and a burgeoning dairy industry paying scant attention to the environmental consequences of its rapid growth.

It is profoundly depressing to hear pundits and politicians talking about the prospects for economic growth with no reference to either equity or environmental constraints. In the case of New Zealand a “rock star” economy can apparently develop accompanied by dismaying levels of child poverty, excited expectations of new oil and gas discoveries which spell disaster for the climate, and a burgeoning dairy industry paying scant attention to the environmental consequences of its rapid growth. Uncertainties attend the predictions of climate science, as the scientists themselves are careful to acknowledge. Reluctant policy makers use this uncertainty to support a “wait and see” response to climate change. Prominent American economists

Uncertainties attend the predictions of climate science, as the scientists themselves are careful to acknowledge. Reluctant policy makers use this uncertainty to support a “wait and see” response to climate change. Prominent American economists

“We can’t make sense of our future until we make sense of our past”, writes

“We can’t make sense of our future until we make sense of our past”, writes