New Zealand could be amongst the first places in the world to feel the effects of ocean acidification, according to a new “emerging issues” paper released today by the Royal Society of New Zealand. Surrounded by cold oceans which absorb CO2 faster than warm waters, and with a $300 million shellfish industry based on mussels, oysters, scallops and paua, NZ is vulnerable to disruptions in the carbonate chemistry used by these animals to build their shells, but the risks cannot be quantified at present.

New Zealand could be amongst the first places in the world to feel the effects of ocean acidification, according to a new “emerging issues” paper released today by the Royal Society of New Zealand. Surrounded by cold oceans which absorb CO2 faster than warm waters, and with a $300 million shellfish industry based on mussels, oysters, scallops and paua, NZ is vulnerable to disruptions in the carbonate chemistry used by these animals to build their shells, but the risks cannot be quantified at present.

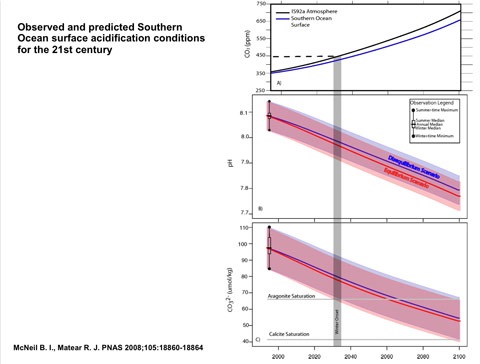

At a briefing to launch the paper, Professor Keith Hunter of the University of Otago pointed to recent work which suggests that for creatures that build their skeletons from a form of calcium carbonate called aragonite, the Southern Ocean could be reaching a critical point as early as the 2030s, as this slide shows:

The magic number is 450 ppm: at that point low pH waters in winter could begin to make it difficult for creatures to build aragonite skeletons or shells. How this might cascade through marine ecosystems is unknown, because the impact on different species can vary through their lifecycle and by season. Some species are also known to be able to adapt. Sydney rock oysters, for example, have been bred to withstand more acid conditions, but it’s not known whether this sort of work would be possible with mussels and other shellfish.

Work on ocean acidification is beginning to provide a valuable and independent line of evidence supporting the need to shoot for stabilisation of atmospheric CO2 at low levels. It may also point to problems with emissions trajectories that are allowed to “overshoot” the desired target: if oceanic CO2 uptake does produce a biologically critical response, exceeding that point might be very bad news for oceanic ecosystems.

The new Royal Society paper gives a very useful overview of what we currently know about ocean acidification and its potential to impact New Zealand ecosystems and marine farming operations. The RS is also organising a workshop in September to discuss the issue.

[Dimmer]

My two cents worth here is to note that Keith Hunter is an absolutely excellent chemical oceanographer.

In paragraph 3 I think you mean low pH, not high pH (the story seemed to be that you get winter maxima in acidification and hence aragonite undersatuation as CO2 is more soluble in cold water).

Aaargh. Fixed. (Of course I meant a high concentration of hydrogen ions…)

No worries, just delete the second part of my comment if you like as it no longer makes sense (and this one)

Nope. It’s good to have the external sub-editing process transparent. 😉

Actually, Carol, the increased solubility of CO2 in winter is a small effect. Photosynthesis drives pH up and respiration drives it down. We get the least level of photosynthesis (versus respiration) in winter, hence lower pH.

Thanks Keith. Noted.