Oxfam NZ’s Barry Coates continues his series of on the spot reports from Cancún: in this episode, he looks at the way international negotiations work…

Negotiations have picked up pace in Cancún. But it is impossible not to feel frustrated with how long it has taken to get to this point. The problem is not just about the past few days in Cancun. Much of the past three years of negotiations has been wasted since the Ministerial meeting in Bali in 2007 that kicked off these negotiations. Government negotiators stated their positions early on, and then in meeting after meeting over the past three years, repeated these positions. Too much of the time and energy of negotiators has been spent trying to score points off each other.

In previous years, the rich nations were very good at doing this and used un-transparent and biased processes to get their own way. This is particularly the case in venues such as the World Trade Organisation. The last time I was in Cancún was for the WTO talks in 2003. After huge protests and the tragic death of a Korean farmer, the talks collapsed in spectacular fashion. The African group walked out of the Cancun WTO negotiations after an unfair negotiations process (eg. a small group of nations were picked to steer the outcome – the “Green Room” named after the office in Geneva where the practice started) and after rich nations tried to force their own issues (notably the deregulation of international business) onto an agenda that was meant to be about development (the ‘Doha Development Agenda’). Since then the WTO talks have limped along, in perpetual deadlock.

There have been some similar tactics tried in past climate change talks, although the common aims in negotiations on climate change are more obvious than on trade (or should be). This was one of the reasons that the Copenhagen talks last year were so ill-tempered and disappointing.

The world has changed and these unfair negotiating tactics are being challenged. Developing countries have gained negotiating skill and economic power. The tectonic plates of global governance have shifted with the rise in economic and political power of the major developing countries. As a result, developing countries will no longer accept the agendas imposed by the rich nations. And they negotiate skilfully and collectively in groups – including the large and powerful BASIC countries (Brazil, South Africa, India and China), Africa and other regional groups, the radical ALBA group (Bolivia, Venezuela, Cuba, Ecuador, Nicaragua and some Caribbean countries), the low income Least Developed Countries and the moral conscience of the negotiations, the Alliance of Small Island States.

So the good news from this re-alignment is that developed nations will not get away lightly with their attempts to renege on their obligations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. When Japan earlier in the week said they would not agree to a second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, the response from negotiators was sharp and strong. Japan was heavily criticised. Civil society groups have also played an important role – Japan’s announcement was met with campaign actions here in Cancún from NGOs in the Global Campaign for Climate Action, and by campaigners in many countries. It appears that Japan has been surprised by the reaction (I don’t know why they didn’t anticipate it). They are still here, and still negotiating and they may be showing more flexibility than their harsh statement implied (“we will never inscribe our target in the Annex B to the Kyoto Protocol under any circumstances and conditions”).

But in other ways this greater balance of power poses challenges to global governance. In climate change negotiations, as in most UN negotiations, there are two main blocs – developed and developing countries – under the rather outdated UN definitions (developing countries include relatively rich nations like South Korea and Singapore). The two blocs can grind each other into stalemate, as they seek to gain advantage, often through unproductive points scoring. Even the most obvious decisions, such as defining a base year for emissions reductions, take years to agree. The answer to the question was always going to be 1990, as it was under the Kyoto Protocol, but Canada and Croatia resisted because it doesn’t suit their pattern of greenhouse gas emissions. Yesterday, after three years, it appeared that this issue had finally been agreed. Glacial progress.

The United Nations is often blamed for these problems, but really the blame lies in the approach of governments. Despite the attempts of the United States and others to find a new place to negotiate, only the UN can generate the full participation and buy-in that is essential for a global agreement.

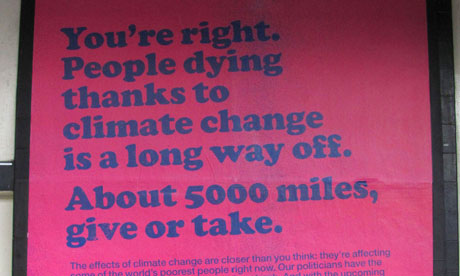

This means that negotiations are taking years, and we are running out of time. Rising greenhouse gas emissions are causing damage and suffering. The World Meteorological Organisation came out with its most recent data earlier this week. It shows that the past decade has been the hottest ever. Temperatures this month will determine whether 2010 is the hottest year since records began. But millions of people around the world know this already. Farmers know that the seasons are changing, that droughts or intense rainfall are destroying their crops and storms are more frequent and intense. Climate change is deadly serious and extremely urgent, particularly to millions of poor and vulnerable people whose lives and livelihoods are at risk.

The good news from Cancún is that there is a real possibility that there will be some meaningful agreement here.

The good news from Cancún is that, despite the glacial progress over the past three years, Japan’s unhelpful announcement, and a myriad of other obstacles, there is a real possibility that there will be some meaningful agreement here. The Mexican government has been fair and transparent in chairing the negotiations, but they have also been insistent that negotiations will not take place on a line-by-line basis, with arguments over every word. They are steering progress forward through informal meetings, the involvement of Ministers (including New Zealand’s Minister of Climate Change Negotiations, Tim Groser), and strong directions by the chairs of working groups. A lot of the real progress in the negotiations is therefore happening outside the formal process, but it is being managed in an open and transparent way. At last, the negotiations are starting in earnest and compromises are getting made.

The agreement will not include everything we want. But it will include some elements that are important for tackling climate change and helping those at risk. In particular, Cancún might agree the basic structure of a fair Climate Fund. Oxfam has been lobbying negotiators to make sure the structure is equitable and effective in getting funding to those who desperately need it. Some of the other issues will need more work to get to a decision, particularly the level of ambitions on emissions reductions. There has been little progress on that so far, but at least Japan and others are still around the table negotiating. We are pushing hard for a clearly defined process beyond Cancun to raise the level of ambition for emissions reductions.

The 2003 collapse of the WTO trade negotiations was a disappointment for the developing countries that were pushing for fairer trade rules, but it had the silver lining of getting issues like investment out of the trade talks. It also sent a strong message that the rich nations could no longer bully their way to get what they want. But we haven’t got time for a collapse of these climate change negotiations. A collapse would mean even more delay and more suffering. As a T-shirt in Cancun worn by youth delegates here says: “You have been negotiating all my life. You cannot tell me you need more time.”

We need a global agreement – a fair, ambitious and binding agreement. It is clear that an agreement won’t be signed here. But if we get the right result from Cancun, signing the deal in Durban next year becomes a real possibility. We have no more time.

Like this:

Like Loading...

I thought of Oxfam’s recent report on food justice while I was reviewing Christian Parenti’s book Tropic of Chaos. He wrote of how climate change impacts are compounding the existing economic and political problems of many poorer populations. This is also very evident in Oxfam’s report on the alarming new surge in hunger as higher food prices hit poor countries. Time for a post on the report, I thought.

I thought of Oxfam’s recent report on food justice while I was reviewing Christian Parenti’s book Tropic of Chaos. He wrote of how climate change impacts are compounding the existing economic and political problems of many poorer populations. This is also very evident in Oxfam’s report on the alarming new surge in hunger as higher food prices hit poor countries. Time for a post on the report, I thought.

Gareth’s

Gareth’s