I watched Stephen Sackur interview James Lovelock on the BBC’s Hard Talk programme on Tuesday evening. It was a depressing experience. Lovelock largely reiterated the things he said in The Vanishing Face of Gaia, reported in my review here.  I listened to it all again. His familiar and seemingly detached expectation that most of the human race will be extinguished  this century. His strong distaste for green solutions, especially wind power. His conviction that all our efforts should now be directed to preparing for life in a diminished world, and that the more time we waste on silly ideas like renewable energy the worse things will be in the end. At present countries like the UK can and should provide a haven for refugees from hotter climates, but there will come a time when the lifeboat is full. I’m not sure how he envisages events unfolding at that point.

I watched Stephen Sackur interview James Lovelock on the BBC’s Hard Talk programme on Tuesday evening. It was a depressing experience. Lovelock largely reiterated the things he said in The Vanishing Face of Gaia, reported in my review here.  I listened to it all again. His familiar and seemingly detached expectation that most of the human race will be extinguished  this century. His strong distaste for green solutions, especially wind power. His conviction that all our efforts should now be directed to preparing for life in a diminished world, and that the more time we waste on silly ideas like renewable energy the worse things will be in the end. At present countries like the UK can and should provide a haven for refugees from hotter climates, but there will come a time when the lifeboat is full. I’m not sure how he envisages events unfolding at that point.

Tag: Monbiot

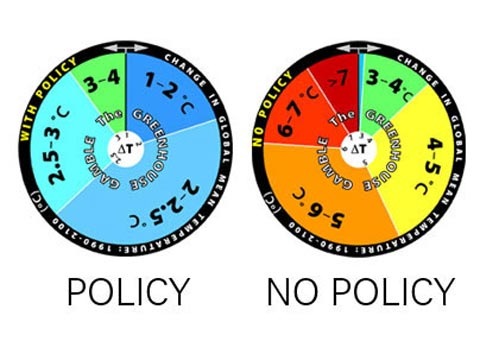

Spinning wheel…

Feeling lucky? Spin these roulette wheels and see where the future lies: on the left, if the world takes decisive action to reduce emissions over the next 100 years, and on the right if we don’t. If we do: most likely an increase of 2 – 2.5ºC. If we don’t: most likely is 5 – 6ºC. Produced by the Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change at MIT, the wheels are a novel way to express the uncertainties associated with projections of future climate and the way they interact with policy decisions. The message for policy makers is clear, according to study co-author Ronald Prinn:

“There’s no way the world can or should take these risks,” Prinn says. And the odds indicated by this modeling may actually understate the problem, because the model does not fully incorporate other positive feedbacks that can occur, for example, if increased temperatures caused a large-scale melting of permafrost in arctic regions and subsequent release of large quantities of methane, a very potent greenhouse gas. Including that feedback “is just going to make it worse,” Prinn says.

For a reminder of just what six degrees means, I recommend Mark Lynas. George Monbiot suggests that climate cranks will object to model projections like these:

Climate change deniers hate these models. Why, they say, should we base current policy on scenarios and computer programmes rather than observable facts? But that’s the trouble with the future: you can’t observe it. If you reject the world’s most sophisticated models as a means of forecasting likely climate trends, you must suggest an alternative. What do they propose? Gut feelings? Seaweed? Chicken entrails?

Tea leaves, obviously…

There she goes, my beautiful world

Ian McEwan is one of my favourite writers. By chance, whilst reading George Monbiot’s latest offering in the Guardian this morning, I stumbled on a link to an essay by McEwan welcoming Barack Obama, outlining the considerable climate policy challenge he (and we) face. The world’s last chance is a superb summary of the current situation, and a masterful piece of writing. Any article that starts like this deserves a read:

Ian McEwan is one of my favourite writers. By chance, whilst reading George Monbiot’s latest offering in the Guardian this morning, I stumbled on a link to an essay by McEwan welcoming Barack Obama, outlining the considerable climate policy challenge he (and we) face. The world’s last chance is a superb summary of the current situation, and a masterful piece of writing. Any article that starts like this deserves a read:

‘I refute it thus!” was Samuel Johnson’s famous, beefy riposte one morning after church in 1763. As he spoke, according to his friend James Boswell, he kicked “with mighty force” a large stone “till he rebounded from it”. The good doctor was contesting Bishop Berkeley’s philosophical idealism, the view that the external, physical world does not exist and is the product of the mind. It was never much of a disproof, but we can sympathise with its sturdy common sense and physical display of Anglo-Saxon, if not Anglican, pragmatism.

Still, we may have proved Berkeley partially correct; in an age of electronic media, where rumour, opinion and fact are tightly interleaved, and where politicians must sing to compete for our love, public affairs have the quality of a waking dream, a collective solipsism whose precise connection to the world of kickable stones is obscure, though we are certain that it exists.

His take on the state of play echoes mine (and Monbiot’s), but he puts it much better than I (or Monbiot) ever will:

Within the climate science community there is a faction darkly murmuring that it is already too late. The more widely held view is hardly more reassuring: we have less than eight years to start making a significant impact on CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions, eight years to move from Berkeley’s solipsism to Johnson’s pragmatism. Thereafter, as tipping points are reached, as feedback loops strengthen, the emissions curve will rise too quickly for us to restrain it. In the words of John Schellnhuber, one of Europe’s leading climate scientists and chief scientific adviser to Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, “what is required is an industrial revolution for sustainability, starting now”.

If you read nothing else today, read this. And the Monbiot’s worth a look too, as is the Nick Cave title reference…

For the benefit of mankind

[youtube]OG_1mgKOb6k[/youtube]

Last weekend I drew attention to Monbiot’s musings on financial and ecological crises. This weekend it’s ecological economist Herman Daly explaining in simple terms why economic growth has become uneconomic growth: we’re getting less wealth and more illth (hat tip: Things Break). That leads nicely to New Scientist’s special issue on The Folly of Growth – covered in detail at Things Break (follow the links there), and also under discussion at frogblog. There are limits to growth and we’re hitting them, but we lack the political and economic tools to deal with the problem. In that context, check out the recent PBS documentary Heat: it opens with an Indian scientist opining:

We are standing at the precipice of hell. If everybody else was to live as an American, we’re doomed.

See also: Nick “Report” Stern’s call for green solutions to the financial crisis. He can’t avoid the word growth, but at least he’s proposing less illth.

Love Minus Zero/No Limit?

Required reading this weekend: George Monbiot muses on the links between the financial crisis and the ecological crisis he believes we inevitably face.

As we goggle at the fluttering financial figures, a different set of numbers passes us by. On Friday, Pavan Sukhdev, the Deutsche Bank economist leading a European study on ecosystems, reported that we are losing natural capital worth between $2 trillion and $5 trillion every year, as a result of deforestation alone. The losses incurred so far by the financial sector amount to between $1 trillion and $1.5 trillion.

As it happens, Sukhdev was interviewd by Kathryn Ryan on RNZ National last week: she kept getting her trillions confused with billions – numbers too big to conjure with (stream, MP3), numbers too frightening to admit easily (Economics of Ecosystems & Biodiversity report here). Monbiot continues:

The two crises have the same cause. In both cases, those who exploit the resource have demanded impossible rates of return and invoked debts that can never be repaid. In both cases we denied the likely consequences. I used to believe that collective denial was peculiar to climate change. Now I know that it’s the first response to every impending dislocation.

From this perspective, climate change is one symptom of a bigger resource and ecosystem crunch. We live in interesting times…