Eleven French journalists – writers and photographers of Collectif Argos – visited some of the people who live on the front line of climate change. Their report was first published in France in 2007, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has now published an English version: Climate Refugees. It invites reading. The written narratives are engaging and immediately informative. The related photographic sections are strikingly alive and stir the imagination. But it’s not lightly done -– the journalists spent time staying with the people whose lives they describe and there’s satisfying depth to the stories and the pictures.

Nine places were visited: Alaska and New Orleans in the US, the low-lying halligen on the North Sea coast of Germany, Lake Chad in Africa, the village of Longbaoshan near Beijing in China, Himalayan Nepal, the small town of Mushiganj in the south west corner of Bangladesh, the Maldives in the Indian Ocean and Tuvalu in the Pacific.

Shishmaref is a village of 600 people on the small island of Sarichef off the coast of Alaska in the Arctic Ocean. As their village slowly crumbles into the sea and the whole island moves towards becoming inhabitable by 2050 the issue is not whether they will have to relocate. It’s where they will go. On offer is a move to towns 200 miles away to take advantage of the urban infrastructure. But the Shishmaref Inupiaq are convinced that relocating to a city would be tantamount to “burying their culture, soul, uniqueness and future”. What many would prefer is to recreate the village on a mainland site only 12 miles away. But it would be double the cost – $200 million as against $100 million – and the fear is that the state will not pay the extra.

The village of Longbaoshan, just 38 kilometres north-west of the Beijing suburbs, is not falling into the sea but being slowly buried by advancing sand. Only 700 people now remain. In recent years 200 have already left for the capital.

“My fields are nothing but stones and sand, sand and stones. Where’s the soil? Where’s the rain? The sky is my only hope, the only way we are able to eat. After the big storm in the spring of 2000, my son had to leave. He became a cook at a restaurant in a Beijing suburb. We don’t see him any more.”

The journalists went to the city to track down a couple who made the move, leaving their young son with his grandfather. They found them working very long hours and living in a nine-square-metre single room.

Around the town of Mushiganj in Bangladesh it’s too much water which is driving people away from their homes. Bangladeshis are accustomed to flooding and have learned to use it to their benefit. But global warming has added a scope and duration to floods which are destroying that balance. In the area the journalists visited the salinity of the soil has increased and crops have been replaced by shrimp farms, which bring far fewer jobs than rice paddies. Drinking water has to be fetched in exhausting trips. The nearby mangrove forests of the Sundarbans offer some fishing and other resources but are infested with pirates and are the refuge of the dangerous Bengal tiger. So for many it’s Dhaka for employment and income, albeit in demanding and exhausting work such as rickshaw driving.

The climate change pressures on Bangladesh will only increase and Dhaka will simply be unable to absorb the large-scale rural exodus anticipated. Where will people go? The journalists spoke with a geography professor who rules out neighbouring India and Myanmar as destinations for political and climate change reasons. He looks for cooperation outside southern Asia in preparing for the massive migrations anticipated.

“I think that countries with larger land areas will have to change their immigration policies. If we believe climate change is a global problem. then we must look for global solutions. Trying to solve it at national level is a mistake.”

Another researcher put it this way:

“For a long time now, I’ve been proposing the following solution. Each country must take responsibility for – in other words transport and accommodate – a quota of climate refugees proportional to its past and present greenhouse gas emissions.”

The water problem in Lake Chad is quite a different one. The lake is disappearing and taking life with it. Over the past 40 years it has lost 90% of its area, shrinking from 25,000 to 2500 square kilometres. A UNESCO statement describes the gradual drying up of the lake as the most spectacular example of the effects of climate change in tropical Africa, attributing it to low amounts of rainfall, evapotranspiration from high temperatures and a series of severe droughts. The effects on the surrounding populations are harsh. “God needs to send us a miracle because there’s too much suffering involved in living on the lake.”

When the journalists began their stay in Tuvalu they record that they couldn’t help feeling some irritation at what they saw as the carefree attitude and love of the easy life of the Tuvaluans. However further acquaintance revealed a pragmatic people fully aware of their inevitable fate and wanting to do everything in their power to stay on their land as long as possible, though involved in a global struggle to negotiate their relocation under optimal conditions. The Chief of Staff at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs:

“We asked the governments of Australia and New Zealand to acknowledge the concept of climate refugees. They refused, saying that, according to international law, refugees can only be people subject to persecution or political, ideological, ethnic or religious pressure – a narrow definition that suits them just fine.”

The journalists, however, wonder whether, based on current scientific knowledge, the existence of climate refugees may give rise to the concept of ‘environmental persecution’ of the most vulnerable populations by the major greenhouse-gas emitters. This could be, they suggest, the beginning of climate justice in which the biggest polluters per inhabitant would not be able to turn away Tuvaluans forced to flee their land.

The Maldives face a similar prospect to the Tuvaluans. The valley residents of Nepal are seriously threatened by growing number of glacial lakes high above them that are becoming engorged with water from receding glaciers and may explode in outburst floods. Many former residents of New Orleans have been relocated in Houston and elsewhere in the US. The sparse population of the halligen in the meantime have a great deal of government money spent on keeping them in their threatened enironment because protecting the halligen means helping protect the mainland.

What is the rest of the world going to do if under the pressures of climate change it becomes apparent that large numbers of people must move from where they now live and work? The book puts that question squarely in front of us. Some of the migration will be within national borders. That will be demanding enough. But some will have to be beyond those borders. Will the rich nations face up to the responsibility they have incurred? Will ethical imperatives survive the crunch times ahead? It would be a hard heart which looked at the photographs in this book and didn’t hope so.

[Buy via Fishpond (NZ), Amazon.com, Book Depository (UK)]

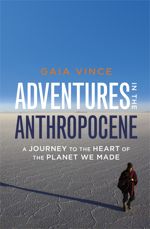

Science journalist Gaia Vince left her desk at Nature and spent two years visiting places around the world, some of them very isolated, where people were grappling with the conditions of what is sometimes described as a new epoch, the Anthropocene. It dates from the industrial revolution and represents a different world from the relatively settled Holocene in which human civilisation was able to develop. Adventures in the Anthropocene tells the story of Vince’s encounters with some remarkable individuals and their communities. It also includes lengthy musings on the technologies the future may employ as humanity faces the challenges of climate change, ocean acidification, population growth, resource depletion and more.

Science journalist Gaia Vince left her desk at Nature and spent two years visiting places around the world, some of them very isolated, where people were grappling with the conditions of what is sometimes described as a new epoch, the Anthropocene. It dates from the industrial revolution and represents a different world from the relatively settled Holocene in which human civilisation was able to develop. Adventures in the Anthropocene tells the story of Vince’s encounters with some remarkable individuals and their communities. It also includes lengthy musings on the technologies the future may employ as humanity faces the challenges of climate change, ocean acidification, population growth, resource depletion and more.

An interesting

An interesting  In this guest post, Mark Lynas, author of

In this guest post, Mark Lynas, author of