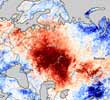

One of the things that persuaded Gwynne Dyer that it was time to write his book Climate Wars was the realisation that “the first and most important impact of climate change on human civilization will be an acute and permanent crisis of food supply”. He’s not the only one to recognise that. Many of us hearing about what the Russian heat wave is doing to crops have no doubt been wondering what the effect of so much loss might be on global supplies. Right on cue Lester Brown, whose Plan B books always lays great stress on food reserves, has produced an updateon what the failed harvest in Russia might mean.

One of the things that persuaded Gwynne Dyer that it was time to write his book Climate Wars was the realisation that “the first and most important impact of climate change on human civilization will be an acute and permanent crisis of food supply”. He’s not the only one to recognise that. Many of us hearing about what the Russian heat wave is doing to crops have no doubt been wondering what the effect of so much loss might be on global supplies. Right on cue Lester Brown, whose Plan B books always lays great stress on food reserves, has produced an updateon what the failed harvest in Russia might mean.

“Russia’s grain harvest, which was 94 million tons last year, could drop to 65 million tons or even less. West of the Ural Mountains, where most of its grain is grown, Russia is parched beyond belief. An estimated one fifth of its grainland is not worth harvesting. In addition, Ukraine’s harvest could be down 20 percent from last year. And Kazakhstan anticipates a harvest 34 percent below that of 2009. (See data.)”

He notes that the heat and drought are also reducing grass and hay growth, meaning that farmers will have to feed more grain during the long winter. Moscow has already released 3 million tons of grain from government stocks for this purpose. Supplementing hay with grain is costly, but the alternative is reduction of herd size by slaughtering, which means higher meat and milk prices.

The Russian ban on grain exports and possible restrictions on exports from Ukraine and Kazakhstan could cause panic in food-importing countries, leading to a run on exportable grain supplies. Beyond this year, there could be some drought spillover into next year if there is not enough soil moisture by late August to plant Russia’s new winter wheat crop.

The grain-importing countries have in recent times seen China added to their list. In recent months China has imported over half a million tons of wheat from both Australia and Canada and a million tons of corn from the US. A Chinese consulting firm projects China’s corn imports climbing to 15 million tons in 2015. China’s potential role as an importer could put additional pressure on exportable supplies of grain.

The bottom line indicator of food security, Brown explains, is the amount of grain in the bin when the new harvest begins. When world carryover stocks of grain dropped to 62 days of consumption in 2006 and 64 days in 2007, it set the stage for the 2007–08 price run-up. World grain carryover stocks at the end of the current crop year have been estimated at 76 days of consumption, somewhat above the widely recommended 70-day minimum. A new US Department of Agriculture estimate is due very soon, which will give some idea of how much carryover stocks will be estimated to drop as a result of the Russian failure.

We don’t know what all this will mean for world prices. The prices of wheat, corn, and soybeans are actually somewhat higher in early August 2010 than they were in early August 2007, when the record-breaking 2007–08 run-up in grain prices began. Whether prices will reach the 2008 peak again remains to be seen.

Brown performs the obligatory ritual of acknowledging that no single event can be attributed to global warming, though I would have thought that by now that proviso could be taken as read. It’s surely more important to affirm, as of course he does, that extreme events are an expected manifestation of human-caused climate change, and their effect on food production must be a major concern.

“That intense heat waves shrink harvests is not surprising. The rule of thumb used by crop ecologists is that for each 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature above the optimum we can expect a reduction in grain yields of 10 percent. With global temperature projected to rise by up to 6 degrees Celsius during this century, this effect on yields is an obvious matter of concern.”

Demand isn’t going down to match the reduction:

“Each year the world demand for grain climbs. Each year the world’s farmers must feed 80 million more people. In addition, some 3 billion people are trying to move up the food chain and consume more grain-intensive livestock products. And this year some 120 million tons of the 415-million-ton U.S. grain harvest will go to ethanol distilleries to produce fuel for cars.”

And the obvious conclusion:

“Surging annual growth in grain demand at a time when the earth is heating up, when climate events are becoming more extreme, and when water shortages are spreading makes it difficult for the world’s farmers to keep up. This situation underlines the urgency of cutting carbon emissions quickly—before climate change spins out of control.”

There’s a podcast in which Lester Brown speaks at greater length, elaborating the matters covered in his written update, and amongst other things commenting on how we might be thankful, from a global grain harvest perspective, that it was Moscow and not Chicago or Beijing which experienced temperatures so far above the norm. The grain loss would have been much higher in either case.

It’s worth adding that while the Russian event is dramatic in terms of its obvious impact on exports of grain globally, there are plenty of other places where food production is threatened by extreme events or by other trends which are in line with climate change predictions. It is impossible to look at the vast flooding of land in Pakistan and not wonder how they will cope with the washing away of millions of hectares of crops — there have been “huge losses” according to the BBC.

“We need to cut carbon emissions and cut them fast.”