Naomi Klein has been to Bolivia. She reports in the Guardian on the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earthheld this week.

Naomi Klein has been to Bolivia. She reports in the Guardian on the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earthheld this week.

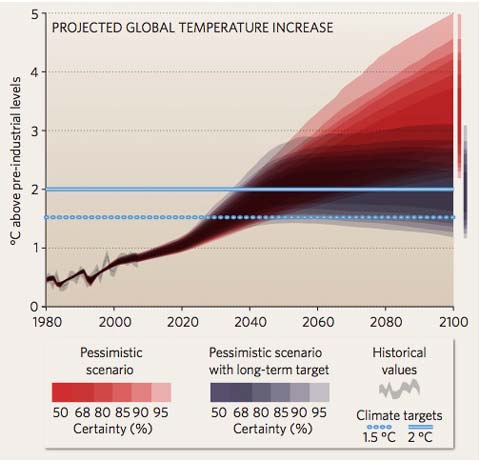

The Copenhagen Accord speaks of keeping global warming to two degrees. In fact to date the emissions reductions pledged under the Accord put the world on the path to three degrees. But two degrees, Morales told the conference, “would mean the melting of the Andean and Himalayan glaciers.”

Klein points out that Bolivia is in the midst of a dramatic political transformation which has nationalised key industries and elevated the voices of indigenous peoples.

“But when it comes to Bolivia’s most pressing, existential crisis – the fact that its glaciers are melting at an alarming rate, threatening the water supply in two major cities – Bolivians are powerless to do anything to change their fate on their own.”

Only deep emission cuts in the industrialised world can avert the catastrophe facing countries like Bolivia and Tuvalu. That’s what the leaders of endangered nations argued for passionately at Copenhagen. “They were politely told the political will in the north just wasn’t there.”

They were also shut out of the closed door negotiations which led to the Accord. And when Bolivia and Ecuador refused to endorse the Accord the US government cut their climate aid by $3 million and $2.5 million respectively. “It’s not a freerider process,” was the explanation of US climate negotiator Jonathan Pershing. That strikes me as an extremely ironic statement given the disproportionate emissions of the US, a point which Klein makes in this way:

“Anyone wondering why activists from the global south reject the idea of ‘climate aid’ and are instead demanding repayment of ‘climate debts’ has their answer here.”

Klein goes so far as to say that the message in Pershing’s words was that if you are poor you don’t have the right to prioritise your own survival. This is the context for her characterisation of the conference as “a revolt against this experience of helplessness, an attempt to build a base of power behind the right to survive.”

There were four big ideas proposed for the conference by the Bolivian government:

- “That nature should be granted rights that protect ecosystems from annihilation (a ‘universal declaration of Mother Earth rights’);

- that those who violate those rights and other international environmental agreements should face legal consequences (a ‘climate justice tribunal’);

- that poor countries should receive various forms of compensation for a crisis they are facing but had little role in creating (‘climate debt’);

- and that there should be a mechanism for people around the world to express their views on these topics (‘world people’s referendum on climate change’).”

Seventeen civil society working groups worked for weeks online and for a week together to prepare recommendations. Klein describes the process as “fascinating but far from perfect”, and suggests that its most important contribution may be Bolivia’s enthusiastic commitment to participatory democracy.

She thinks this because of her concern that after the failure of Copenhagen the idea that democracy is at fault “went viral”. The UN process of votes to 192 countries is too cumbersome and solutions are better found in small groups. She sees James Lovelock’s recent statement as an example: “It may be necessary to put democracy on hold for a while.”

Klein won’t have a bar of this. It is the small groupings which have caused us to lose ground and weakened already inadequate existing agreements. She notes that Bolivia came to Copenhagen with a climate change policy drafted by social movements through a participatory process, resulting, in her view, in the most transformative and radical vision so far.

She sees the people’s conference as Bolivia trying to take what it has done at national level and globalise it, inviting the world to participate in drafting a joint climate agenda ahead of the next UN climate conference in Cancun. She quotes Bolivia’s ambassador to the United Nations, Pablo Solón: “The only thing that can save mankind from a tragedy is the exercise of global democracy.”

Her conclusion:

“If he is right, the Bolivian process might save not just our warming planet, but our failing democracies as well. Not a bad deal at all.”

Whatever one makes of the various avenues being pursued (if that’s not too strong a word) in achieving emission reductions, there is a need for the voices of the most endangered nations to be heard. It seems likely that they will need to be raised to the level of loud and clear before a great deal of notice is taken of them. Bolivia recognises its vulnerability to glacier melt, and to various other threats which were identified in an Oxfam report last year discussed here on Hot Topic. It would be a failure of a government’s duty to its citizens to remain quiet. Their steps to mobilise global opinion should not be treated with indifference or contempt. And it is to be hoped that the US cutting off of funding will be reversed. It looked suspiciously like punishment, and undeserved at that.

Well, a group with a well-earned reputation for independent investigative journalism has followed the money trail of the climate change lobby set up to insulate the multibillion dollar industries that have the most to lose from the world’s governments getting serious about tackling climate change.

Well, a group with a well-earned reputation for independent investigative journalism has followed the money trail of the climate change lobby set up to insulate the multibillion dollar industries that have the most to lose from the world’s governments getting serious about tackling climate change. I wrote a

I wrote a