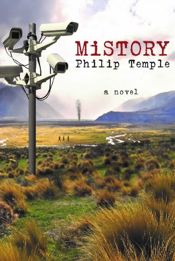

Anyone who follows the science of climate change knows that we are heading for environmental and social turmoil along our current path. In his new novel MiSTORY author Philip Temple imaginatively pictures what that turmoil might mean decades on from now.

Anyone who follows the science of climate change knows that we are heading for environmental and social turmoil along our current path. In his new novel MiSTORY author Philip Temple imaginatively pictures what that turmoil might mean decades on from now.

New Zealand is in a political mess. Conflict abroad and conflict within. A long-lasting state of emergency, the suspension of elections, a sinister security force exercising surveillance and seeking out the resistance force which has emerged since the SoGreens were banished from political life, decayed infrastructure but an impressive range of digital electronics available to the controlling authorities. All the ingredients for what the chief protagonist, John 21, gradually recognises is “a kind of casual police state, if there can be such a thing, a police state kiwistyle”.

Actually it’s not so casual, as he discovers when he leaves Dunedin for central Otago and joins up with the resistance movement. I won’t detail any of the story here but it is a well-crafted and gripping narrative portraying the Movement’s struggle against the oppressive government, reaching a pitch of sorts in Christchurch which has become the centre of government. It is a struggle in which the central character, not by nature a political activist, finds himself content:

“I realised how much freer I was now, free of all that surveil and control back home, life as a pin number. Things had turned simpler and cleaner…”

Temple has dedicated his book to Generation Zero, the New Zealand youth-led organisation which urges action on climate change. His novel doesn’t labour climate change, but the consequences are everywhere apparent. The sea has inundated parts of Dunedin and Christchurch and the maintenance of infrastructure is clearly a central challenge for a by now threadbare society.

The question that the book poses for readers is whether something like this will be the response of political leaders to the pressures that will come upon society as unrestrained climate change and other consequences of environmental heedlessness develop. Will we avoid the obvious solutions and instead fall into resource conflicts around the globe? Can democracies survive the strains that such conflicts will bring? Will the nasty forces of totalitarianism see and grab their opportunity? Can civilised society hold up against the pressures of environmental and economic breakdown?

There are slim hopes reflected in the book. It is not a chronicle of final devastation and collapse. Such hopes as there are rest in the determination of decent people and their readiness to battle for something more than their own private interests.

It’s always good to see writers infusing their work with concerns for human welfare. Temple was quite direct in an interview with the Otago Daily Times that his intention in the novel was to stimulate debate on such topics as climate change, economic instability and other potential threats to New Zealand’s wellbeing.

On the day I was writing this review it gave me pleasure to read that the winner of this year’s Man Booker prize, Richard Flanagan, said on the BBC that he was “ashamed to be an Australian” because of prime minister Tony Abbott’s environmental policies.

Temple was anxious to publish his book before the election. It would be nice to think it helped focus public attention on the longer horizon issues, but apart from the Greens the major parties generally steered clear of addressing such questions and their media inquisitors certainly didn’t trouble them with much of that nature. The short term remains the limit of most political promise and apparently most public expectation.

Many New Zealand readers will enjoy Temple’s story set in their own cities and mountains. Some may read it as fantasy. But the discerning will recognise that it underlines the warnings that are already blindingly obvious in the world of today.

[Buy MiSTORY from the author’s website, Amazon, and good bookstores.]

There is a growing body of fiction that deals, directly or indirectly, with global warming. This includes work from major novelists such as Barbara Kingsolver. This new genre has been dubbed ‘Cli Fi’, a nice sling off at Sci Fi from which it is derived, and has given new life to the post apocalyptic novel. As the reality of global warming sinks in, we can expect a lot more Cli Fi. Contemporary fiction which ignores it will make itself irrelevant and unreal. The blindingly obvious is beginning to register.

In the face of the difficult challenge of the dealing the Science Fiction-like real world, many of our writers have turned to the past, to historical themes, and literary prizes reward that tendency.

Ahem — right sidebar, third section down — ahem. (Puts away trumpet).

Interesting to note that I’m reading the new Ian McEwan, The Children Act, and in an early section he has the protagonist ruminate on the wet summer London’s been experiencing, including a mention of wayward jet streams caused by melting Arctic sea ice. You could say that McEwan is “mainstreaming” the issue, by making it a part of everyday life for his characters. We will see much more of this, I have no doubt…

The “Aviator” fan club is eagerly waiting the sequel…

Peter Jackson is sure it will evolve into a trilogy of cause. And Weta studios are said to be making blimps in preparation… 😉

Thanks for the observation Kiwipoet. I nearly mentioned both McEwan’s Solar (reviewed on HT) and Margaret Atwood’s Year of the Flood (reviewed on Celsias) in my post. I also enjoyed reading Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Path not so long ago.

See also J G Ballard’s ‘The Drowned World’ from 1962. Set in a 22nd century London that has become a tropical swamp. I read it as a teenager, long before phrases such as ‘global warming’ and ‘climate change’ entered the mainstream.

I’ve never been sure if Ballard had insider knowledge or if he was just lucky to propose a possible sci-fi future that may well come to pass.

Ballard was following in the footsteps of John Wyndham, the British sci-fi thriller writer who specialised in what Brian Aldiss called “cosy catastrophes”. The Kraken Wakes is Wyndham’s sea level rise book, published in the early 50s. I re-read it a year or two ago for an interview with Tim Jones: more about it at that link.

The author of this piece, Philip Temple, has had a pretty interesting life

When he was a young man, he travelled to Western New Guinea and (from his webpage)” made the first ascent of the Carstensz Pyramide, which has come to be regarded as the technically most difficult of the ‘Seven Summits of the Seven Continents’. Later he was the last to witness the tool-making rituals of a stone-age culture before it was overtaken by the modern world. Facing daunting physical odds, he went on to explore a swathe of unmapped central New Guinea highlands, and he risked his life to recover the human remains from a US aircraft that had crashed on a sheer mountain face.”

http://philiptemple.com/non-fiction/the-last-true-explorer-into-darkest-new-guinea.html

He made this trip with Heinrich Harrer, (author of “Seven Years in Tibet” which describes amongst other things his time with the young Dalai Lama before the Chinese occupation).

Temple also managed to survive a 200m fall on a climb of Mt Cook.

I read quite a bit of fiction from the public library and can say it is rare now to find a book set in the near present that does not manage to include climate change in the background at least, though the latest I read “The Man with the Compound Eyes by Wu Ming Ti, managed to include tecktonic mayhem, rising seas, tsunamis, subsidence, erosion, relocation and a current shift causing part of the rubbish of the north pacific gyre to surround Taiwan with ecologic and economic destruction all through the interactions of a handful of characters who hardly know what is going on. .Nevertheless I’m not sure I would call it Cli Fi

I’m told that Christopher Nolan’s upcoming movie, Interstellar, is Cli Fi. Or should that be Sci Cli Fi?