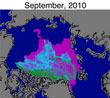

Last week NOAA released the 2010 update of its Arctic Report Card, covering the 2009/10 winter season and 2010 summer sea ice minimum. It makes for sobering reading. Greenland experienced record high temperatures, ice melt and glacier area loss, sea ice extent was the third lowest in the satellite record, and Arctic snow cover duration was at a record minimum. It’s worth digging through the whole report — it’s concise, well illustrated and referenced back to the underlying research — but a couple of things struck me as really important.

The first is the dramatic melting seen in Greenland this summer. From the Greenland report card:

Summer seasonal average (June-August) air temperatures around Greenland were 0.6 to 2.4°C above the 1971-2000 baseline and were highest in the west. A combination of a warm and dry 2009-2010 winter and the very warm summer resulted in the highest melt rate since at least 1958 and an area and duration of ice sheet melting that was above any previous year on record since at least 1978.

And…

Abnormal melt duration was concentrated along the western ice sheet (Figure GL3), consistent with anomalous warm air inflow during the summer (Figure GL1) and abnormally high winter air temperatures which led to warm pre-melt conditions. The melt duration was as much as 50 days greater than average in areas of west Greenland that had an elevation between 1200 and 2400 meters above sea level. In May, areas at low elevation along the west coast of the ice sheet melted up to about 15 days longer than the average. NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis data suggest that May surface temperatures were up to 5°C above the 1971–2000 baseline average. June and August also exhibited large positive melting day anomalies (up to 20 days) along the western and southern ice sheet. During August temperatures were 3°C above the average over most of the ice sheet, with the exception of the northeastern ice sheet. Along the southwestern ice sheet, the number of melting days in August has increased by 24 days over the past 30 years.

Not good news for the ice sheet. The atmosphere report card draws attention to the impact Arctic warming is having further south, dubbing it the warm arctic/cold continents pattern (WACC).

While 2009 showed a slowdown in the rate of annual air temperature increases in the Arctic, the first half of 2010 shows a near record pace with monthly anomalies of over 4°C in northern Canada. There continues to be significant excess heat storage in the Arctic Ocean at the end of summer due to continued near-record sea ice loss. There is evidence that the effect of higher air temperatures in the lower Arctic atmosphere in fall is contributing to changes in the atmospheric circulation in both the Arctic and northern mid-latitudes. Winter 2009-2010 showed a new connectivity between mid-latitude extreme cold and snowy weather events and changes in the wind patterns of the Arctic; the so-called Warm Arctic-Cold Continents pattern.

So now you know where the WACCy winter weather’s coming from…

What observations would force you to conclude that this notion of a place called “Greenland” is fantasy?

Normal human over-optimism, sometimes known as deceiving ourselves.

Why else would anyone name New South Wales as ‘new’ South Wales? Cook may or may not have had South Wales itself in mind when he used this. But simply using these words rather than “strange-place-with-weird-plants-and-animals” indicates the common desire to make one’s discoveries more desirable to the folks back home. And make them more likely to think following you to this new and unknown environment might be a good idea.

The really big issues with global warming are in the sea. The warm water lapping Greenland and West Antarctica is melting the glaciers at the shoreline. Up to now this has not added greatly to the sea levels as the ice is already in the water but as the glacier behind it speeds up and new ice starts to melt then sea levels will start to rise more quickly.

100 gigatonnes of ice raises the sea levels by .23mm. It does not sound much but when you realise Antarctica is twice the size of Australia and the ice is 1.5 kilometres thick you begin to appreciate how bad it can get.

We only need one meter and we are in deep trouble.

and the sea surface temperatures are doing what, exactly, right now, Bob?

Here you go John. SST anomalies right now. Check out the south and west of Greenland.

http://ocean.dmi.dk/satellite/index.uk.php

This one’s a better picture – check out Iceland and Hudson’s Bay.

http://ocean.dmi.dk/satellite/index.uk.php

Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem to record your settings, so to see the relevant data, you need to switch temps to anomalies and pick the relevant maps.

Oh rats. I did choose the maps to illustrate the point – didn’t even check whether the url changed to suit.

Sorry.

The warmer water is melting the glaciers really fast. When the British Antarctic Expedition put their submarine under the Pine Island glacier recently they found that there is a 300 meter gap underneath whereas it should be sitting on the sea bed.

At lot of the reports are very recent and much of Antarctica is still being surveyed but you can tell from the number of research teams going out there that they are worried.

Try the Australian CSIRO for a good overview. http://www.cmar.csiro.au/sealevel/index.html

and the sea surface temperatures are doing what, exactly, right now?

Warming?. According to NOAA

(January to September 2010) The ocean temperature was also the second warmest such period on record (after 1998 – .52C vs .55C above the baseline)

The intensifying La Nina “should” see some cooling for the rest of the year though.

The intensifying La Nina “should†see some cooling for the rest of the year though.

So what caused the warming then?

The warming had multiple causes. Included amongst them were a El Nino and ACC. The likely relative cooling will be the net result of ACC and La Nina. Thus, other things being equal (and they are not, since the ENSO doesn’t necessarily switch between events of equal intensity), the expected cooling during La Nina is likely to be less than the experienced warming during El Nino.

Regardless of La Nina the heat is going into the oceans which continues to soak it up. Thermal expansion amounts to about 300 mm for 1c increase in temperature which is not much increase for a lot of heat.

At .23 mm for every 100 gigatonnes the land glaciers are not going to add up to much but Greenland has the potential for seven meters and Antarctica the potential for 60 meters. 500 mm on top of what we are already getting and we are looking at real problems.

New Zealand is a real nice place but keep it quiet or they will all want to live here.

Tuvalu got in at the head of the line, didn’t they?

“Antarctica the potential for 60 meters.”

While this is true, it’s useful to distinguish between the East Antarctic Ice Self (EAIS) and the West Antarctic Ice Self (WAIS). They have two very different structures.

The EAIS is by far the larger and is almost entirely sitting on bedrock that is above sea-level. While it has melted in the geological past (and when it does it’s capable of raising sea levels by 50m or more)…it’s not likely to do so under any plausible scenario that we know of at present. At least within time scales of many, many centuries.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Antarctic_Ice_Sheet

By contrast the WAIS is a wholly different critter. It’s mostly bedded on rock at depths km below sea level. Because warming ocean currents can directly access it from below the WAIS is inherently far less stable than the EAIS. There is good reason to believe that the WAIS is capable of, and indeed has in the past, broken up in very short time-frames. No-one can be certain whether this breakup would happen in days or decades, but neither can be ruled out.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_Antarctic_Ice_Sheet

If that happens we could sea 5 – 10m sea level rises in catastrophically fast events. Even I feel a sense of ‘alarmism’ come over me when I write that. On the other hand when I’ve personally listened to Prof Tim Naish explain in detail why this is possible…it’s hard to deny.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/6206672.stm

Remember, the guys who actually do the field work, as opposed to carping from comfy armchairs, all know what is going on.

Good points Red! And just a while back we hear that WAIS is being “undermined”.

It must be emphasized that it is thinning of the marine terminating outlet glaciers that reduces friction and leads to acceleration and calving retreat. The thinning can come from bottom melting as Bob notes, under Petermann Glacier this is the bulk of the melting and surface melting. The warm temperatures have created a perfect set of negative feedbacks for the glaciers in northern Greenland of late. Increased bottom melting of floating sections, increased surface melting, higher snowlines expanding the melt zone, and reduced sea ice increasing wave action. Humboldt Glacier is not as sensitive to these changes as Petermann Glacier, since it does not have a substantial floating section.

Gareth, I acquired a copy of the Mahlstein & Knutti paper that appeared in your Twitter feed, and it’s quite the read. Basically it proposes that the low end of the Arctic sensitivity range, being the product of low-resolution models that the paper makes a case for rejecting, be discarded and implies that the same should be done for global sensitivity. It’s worth a post IMHO.

If you could flick me a copy, Steve, that would be helpful… You’ve got my email I think?

Can’t find it offhand. Email me and I’ll shoot it back to you.