James Hansen has long been a leading climate scientist and he is also an excellent communicator of the science to the public. What he had to say about the scientific picture in his recent interview with Bill McKibben, a different aspect of which I highlighted in yesterday’s post, is of interest for its clarity and for the bluntness of its affirmation of how CO2 levels in the atmosphere can be returned to safer levels. The book Hansen refers to in the course of the interview is his Storms of my Grandchildren. The interview is an addition to the latest paperback edition.

McKibben opens by asking about the large number of new national high-temperature records this year. Hansen replies:

“What we see happening with new record temperatures, both warm and cold, is in good agreement with what we predicted in the 1980s when I testified to Congress about the expected effect of global warming. I used coloured dice then to emphasize that global warming would cause the climate dice to be ‘loaded’. Record local daily high temperatures now occur more than twice as often as record daily cold temperatures. The predominance of new record highs over record lows will continue to increase over the next few decades, so the perceptive person should recognize that climate is changing.”

It doesn’t need big hikes in average global temperature to cause major changes.

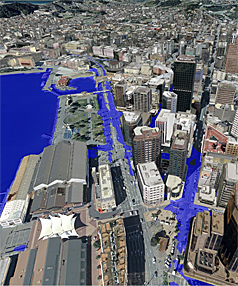

“The last time Earth was 2 degrees warmer so much ice melted that sea level was about twenty-five meters (eighty feet) higher than it is today.”

He recognises the strength of weather variability and warns that it will be increased by global warming:

“But remember that weather variability, which can be 10 to 20 degrees from day to day, will always be greater than average warming. And weather variability will become even greater in the future, as I explain in the book, if we don’t slow down greenhouse gas emissions. If we let warming continue to the point of rapid ice sheet collapse, all hell will break loose. That’s the reason for ‘Storms’ in the book title.”

McKibben then asks about “climategate”, to a robust response from Hansen. An excerpt:

“The NASA temperature analysis agrees well with the East Anglia results. And the NASA data are all publicly available, as is the computer program that carries out the analysis.

“Look at it this way: If anybody could show that the global warming curve was wrong they would become famous, maybe win a Nobel Prize. All the measurement data are available. So why don’t the deniers produce a different result? They know that they cannot, so they resort to theft of e-mails, snipping private comments out of context, and character assassination.

“IPCC’s ‘Himalayan error’ was another hoax perpetrated on the public. The perpetrators, global warming deniers, did a brilliant job of playing the scientifically obtuse media like a fiddle…

“IPCC scientists had done a good job of producing a comprehensive report. It is a rather thankless task, on top of their normal jobs, often requiring them to work sixty, eighty, or more hours per week, with no pay for overtime or for working on the IPCC report. Yet they were portrayed as incompetent or, worse, dishonest. Scientists do indeed have deficiencies—especially in communicating with the public and defending themselves against vicious attacks by professional swift-boaters.

“The public, at some point, will realize they were hoodwinked by the deniers. The danger is that deniers may succeed in delaying actions to deal with energy and climate. Delay will enrich fossil fuel executives, but it is a great threat to young people and the planet.”

Asked about whether we can stop the process of increasing warming and the tipping point dangers it brings with it, whether we can stabilize the situation, Hansen responds:

“We can estimate what is needed pretty well. Stabilizing climate requires, to first order, that we restore Earth’s energy balance. If the planet once again radiates as much energy to space as it absorbs from the sun, there no longer will be a drive causing the planet to get warmer. Restoring planetary energy balance would not immediately stop sea level rise, but it should keep sea level rise small. Restoring energy balance also would prevent climate change from becoming a huge force for species extinction and ecosystem collapse.

“We can accurately calculate how Earth’s energy balance will change if we reduce long-lived greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide. We would need to reduce carbon dioxide by 35 to 40 ppm (parts per million) to increase Earth’s heat radiation to space by one half watt, if other long-lived gases stay the same as today. That reduction would make atmospheric carbon dioxide amount to about 350 ppm.”

There are additional reasons for the 350 ppm target, one of them being ocean acidification; Hansen refers to ocean biologists concluding that for the sake of life in the ocean we need to aim for an atmospheric carbon dioxide amount no higher than 350 ppm. However Earth’s energy balance is the criterion that provides the most fundamental constraint for what must be done to stabilize climate.

McKibben remarks that his organisation, 350.org, meets opposition from some activists who demand an even lower target of 300 ppm or the pre-industrial 280ppm. But Hansen replies that all we can be sure of at present it that it should be ‘less than 350 ppm’, and that is sufficient for policy purposes:

“That target tells us that we must rapidly phase out coal emissions, leave unconventional fossil fuels in the ground, and not go after the last drops of oil and gas. In other words, we must move as quickly as possible to the post–fossil fuel era of clean energies.

“Getting back to 350 ppm will be difficult and will take time. By the time we get back to 350 ppm, we will know a lot more and we will be able to be more specific about what ‘less than 350 ppm’ means. By then we should be measuring Earth’s energy balance very accurately. We will know whether the planet is back in energy balance and we will be able to see whether climate is stabilizing.”

He goes on to explain that it is difficult to specify at this stage an eventual value for CO2 because there are other human-made climate forcings. Methane and tropospheric ozone in the air are among them, and realistic reductions of those gases would alleviate somewhat the amount by which we must reduce CO2.The cooling effect of atmospheric aerosols is likely to be lessened as we improve air quality. It would be foolish to demand a CO2 reduction to 280 ppm at this stage of our understanding.

One of the things Hansen says we must do in our scaling back to 350 ppm is not to go after the last drops of oil and gas. It was rather deflating, therefore, as I was preparing this post to see that today’s NZ Herald carries an upbeat report on the prospects for petroleum exploration in New Zealand waters as the price of oil rises. All the more depressing to see the comments on how exploration-friendly the NZ government is regarded as being.

A Merrill Lynch spokesperson, describing New Zealand as a “sweet spot” for exploration, said the royalty regime in this country was attractive.

“People believe that if you find stuff the Government won’t try and screw them over with an unfriendly tax arrangement.”

Indeed the Government is pro-actively formulating a petroleum action plan to encourage more drilling. It appears to be pursued with a good deal more purpose than any plan to encourage renewable energy development.

What does the government reply to Hansen when he says the world must not go after the last drops of oil and gas? That these are not the last drops? That we don’t believe you? For that matter in possibly allowing the development of the Southland lignite fields what is it saying to the even more pressing need, in Hansen’s view, to rapidly phase out coal emissions?

We should keep pressing such questions on the NZ government. We must not allow them to thumb their noses at the science.

Like this:

Like Loading...