New Zealand’s merry little band of climate deniers are turning out to be a right bunch of Cnuts. Sea level rise and its implications for Christchurch and the wider world have been making news in recent weeks — as have new projections of rapid sea level rise over the remainder of this century. So what does a good climate denier do? To stay faithful to their core belief — that climate change isn’t happening, or isn’t going to be bad — they have to argue against policies designed to deal with its impacts, as well as those intended to cut carbon emissions. Sea level rise? Like Cnut, they line themselves up against the waves.

New Zealand’s merry little band of climate deniers are turning out to be a right bunch of Cnuts. Sea level rise and its implications for Christchurch and the wider world have been making news in recent weeks — as have new projections of rapid sea level rise over the remainder of this century. So what does a good climate denier do? To stay faithful to their core belief — that climate change isn’t happening, or isn’t going to be bad — they have to argue against policies designed to deal with its impacts, as well as those intended to cut carbon emissions. Sea level rise? Like Cnut, they line themselves up against the waves.

I’ve blogged many times on the challenge sea level rise poses for post-quake Christchurch. The 2011 quakes caused large parts of the city to drop by up to half a metre — effectively delivering decades of sea level rise in a matter of minutes. For some areas of the city tidal and run-off flooding are now commonplace.

The current debate on sea level issues has been prompted by the city council’s long term planning process — which recommends ((Based on a revised report (pdf) developed from consultants Tonkin & Taylor’s 2014 work.)) that development should be restricted in areas where future sea level rise is expected to cause problems. Not surprisingly, this has some owners of coastal properties concerned that they will lose out. The council has also looked at the idea of building a tidal barrier across the Avon-Heathcote estuary to protect the city.

Local politics and property owner self-interest is bumping into the harsh realities of climate change, leading to a wide variety of responses — including “it isn’t happening”.

Continue reading “Postcards from La La Land: the Cnut conundrum”

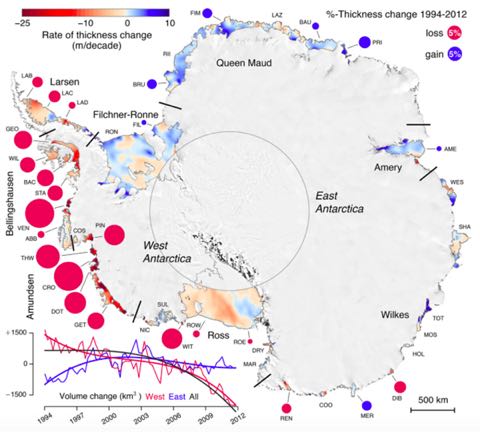

Much news in recent weeks from Antarctica, and none of it good. An Argentinian base on the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula recently reported

Much news in recent weeks from Antarctica, and none of it good. An Argentinian base on the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula recently reported

Science journalist

Science journalist  In which I pull together the strands of the recent bad news from Antarctica and Greenland, and lament the loss of the coastline we all grew up with — no longer a theoretical possibility but a long term certainty. Check out

In which I pull together the strands of the recent bad news from Antarctica and Greenland, and lament the loss of the coastline we all grew up with — no longer a theoretical possibility but a long term certainty. Check out

You must be logged in to post a comment.