Two items during this week highlighted the continuing progress of Solid Energy’s intentions to develop the Southland lignite fields. I therefore provide this depressing update to two Hot Topic posts on the issue late last year. Don Elder (left), CEO of state-owned enterprise Solid Energy, appeared before the Commerce select committee during the week and announced that the proposed lignite developments will be worth billions. And it appears that this will be the case even if they don’t receive free carbon credits under the ETS, which they appear to nevertheless hope for. There was a slight acknowledgement that there were carbon footprint issues still to be resolved and some soothing suggestions, reported in the Otago Daily Times, that approaches such as mixing synthetic diesel with biofuels, carbon capture and storage, and planting trees, could reduce the net emissions. With a convenient fall-back – that the company could pay someone elsewhere in the world to do this for it. There is little evidence that carbon capture and storage will feature as anything more than talk in this scenario. The wildest extremity of the CCS option was touched on outside the committee when Elder spoke of the possibility of eventually piping carbon out to sea and pumping it into sea-floor oil or gas wells, after the Great South Basin has been developed.

Two items during this week highlighted the continuing progress of Solid Energy’s intentions to develop the Southland lignite fields. I therefore provide this depressing update to two Hot Topic posts on the issue late last year. Don Elder (left), CEO of state-owned enterprise Solid Energy, appeared before the Commerce select committee during the week and announced that the proposed lignite developments will be worth billions. And it appears that this will be the case even if they don’t receive free carbon credits under the ETS, which they appear to nevertheless hope for. There was a slight acknowledgement that there were carbon footprint issues still to be resolved and some soothing suggestions, reported in the Otago Daily Times, that approaches such as mixing synthetic diesel with biofuels, carbon capture and storage, and planting trees, could reduce the net emissions. With a convenient fall-back – that the company could pay someone elsewhere in the world to do this for it. There is little evidence that carbon capture and storage will feature as anything more than talk in this scenario. The wildest extremity of the CCS option was touched on outside the committee when Elder spoke of the possibility of eventually piping carbon out to sea and pumping it into sea-floor oil or gas wells, after the Great South Basin has been developed.

Tag: NZ

Here comes the flood

News today of interesting new research on the effect of rising sea levels on 180 US coastal cities by the century’s end. University of Arizona scientists will be publishing a paper this week in Climatic Change Letters which sees an average 9 per cent of the land within those cities threatened by 2100. The Gulf and southern Atlantic cities, Miami, New Orleans, Tampa, Fla., and Virginia Beach, Va. will be particularly hard hit, losing more than 10 per cent of their land area.

The research is the first analysis of vulnerability to sea-level rise that includes every U.S. coastal city in the contiguous states with a population of 50,000 or more. It takes the latest projections that the sea will rise by about 1 metre by the end of the century at current rates of greenhouse gas emissions and thereafter by a further metre per century. The researchers examined how much land area could be affected by 1 to 6 metres of sea level rise. At 3 metres, on average more than 20 per cent of land in those cities could be affected. Nine large cities, including Boston and New York, would have more than 10 per cent of their current land area threatened. By 6 metres about one-third of the land area in U.S. coastal cities could be affected.

The study has created digital maps to delineate the areas that could be affected at the various levels. The maps include all pieces of land that have a connection to the sea and exclude low-elevation areas that have no such connection. Rising seas do not just affect seafront property – water moves inland along channels, creeks, inlets and adjacent low-lying areas.

“Our work should help people plan with more certainty and to make decisions about what level of sea-level rise, and by implication, what level of global warming, is acceptable to their communities and neighbours,” said one of the co-authors.

An interesting notion, that of deciding how much sea level rise is acceptable. Shades of King Canute? It’s presumably the speaker’s way of pointing out that it may still be within our power to keep it manageable if we begin an urgent and drastic reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Or perhaps he’s hinting at a time where only relocation will serve. For the present some adaptation measures are now unavoidable and should be planned for, but hopefully the digital maps of this study will help convince people that mitigation is also essential. Not seemingly the Republican majority in the House which bizarrely rampages on as if human-caused climate change isn’t happening, let alone in need of mitigation.

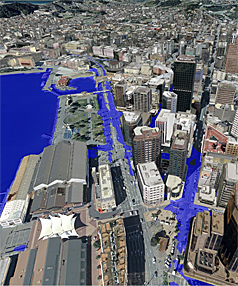

I wonder how much similar mapping has been done in the case of New Zealand coastal cities. The Wellington City Council has gone so far as to consider a computer-generated graphic (pictured) which visualised the effect of a one metre rise in sea level on the city. Nelson has considered a commissioned report on climate change effects which warned that a 1 metre sea level rise would have water lapping at the airport. I don’t recall seeing anything which indicates that Auckland has seriously looked at the effect. Christchurch is planning for a 50 cm sea level rise this century with the recognition that it may be higher and presumably that means they are undertaking detailed consideration of vulnerable areas. Dunedin has had the benefit of some University of Otago modelling of a 1.5 metre sea level rise, reported here, with assurance from the new Carisbrook stadium that they’re 3.7 metres above mean sea level. I’ve written earlier on encouraging signs that local body government in New Zealand, at least in some areas, is facing up to the responsibilities for adaptation. In some cases this has meant taking on mitigation measures as an obvious consequence, though Environment Waikato’s Proposed Regional Policy Statement states that the Council’s role is to prepare for and adapt to the coming changes and that response in terms of actions to reduce climate change is primarily a central government rather than a local government role. I’ll be challenging that in my submission, since it seems to me that engaging people locally in mitigation effort is both possible and sensible, especially when they can see locally what the prospects will likely be without it.

The costs of coping with sea level rise look likely to be enormous. If in fact that is what future populations have to do they will look back in wonderment on the argument represented by such as our present government that we were unable to do anything deeply serious about mitigating the effects of climate change because we thought it might affect our economy adversely. True, we might have to acknowledge, there was a Stern review which pointed out that the costs facing you, our descendants, would dwarf the adjustments required of us, but somehow we couldn’t get over our hump to reduce your mountain.

Lessons from a drowning continent: no time like the present to invest in our future

Jim Salinger’s spending the summer at the University of Tasmania in Hobart. This reflection on the lessons of Australia’s recent floods first ran in the Waikato Times at the beginning of the month, but I felt it deserved a wider audience and so with Jim’s permission reproduce it here.

As I watch from my summer roaring forties perch in Hobart, Tasmania the somewhat unprecedented rains that are deluging parts of Australia raise some pertinent lessons on climate and risk management for New Zealand. Firstly let’s look at some figures and ask the question of what are the climate mechanisms behind the deluges.

For December 2010 the Bureau of Meteorology figures show that eastern Australia (the states of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania) had its wettest December on record, with an average area total of 167 mm (132% above normal). What caused Brisbane to flood were the heavy falls to the north and west between 10-12 January with totals for the three days exceeding 200 mm. In Toowoomba over 100 mm fell in less than an hour.

Further south in Victoria heavy rainfall and flash flooding occurred between 10 to 15 January, with more than 100 mm of rain across two thirds of the state. Bureau of Meteorology figures show many weather stations in Victoria have now broken their all-time January records in over 100 years of observationd: 259 mm fell on Dunolly (the previous record was 123 mm), and the 282 mm of rain that fell in 1 day at Faimouth in the north east of Tasmania – the highest 1-day total for any gauge on record for the state.

The extremely wet December had eastern Australia primed for the record floods that were to follow in January. The soil could not take any more moisture and the heavy rains turned into runoff, with record floods in some parts.

The causes of these floods have been laid at the feet of the La Niña climate pattern – the sister of El Niño. La Niña brings strengthened moisture-laden easterly winds on to the Australian continent. This year the La Niña event is strong, with it being amongst the top three in magnitude, ranking with the 1918/19 and 1973/74 events. However there is one distinct difference this season: temperatures in Australia this past decade have been 0.5 deg C warmer than in the 1970s, and 0.9 deg C warmer than in the 1910s, all as a result of global warming. And during the 2010/11 season, La Niña seas off eastern Australia have been much warmer than average, being 1 to 2 deg C above the 1985-1998 average.

It is a simple law of physics that a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture. With the long term heating of the oceans more moisture has been measured in the atmosphere during the last decade. The consequence is that global warming leads to an increase in the magnitude and incidence of heavy rainfall, and the resultant floods.

Global warming has arrived, and the climate has warmed. Global warming is no longer a theory…

The first lesson from the Australian flooding events is that global warming has arrived, and the climate has warmed. Global warming is no longer a theory based on abstract calculations of what the climate is very likely to do in future decades. In 2007 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded that “It is very likely that hot extremes, heat waves and heavy precipitation events will continue to become more frequent.”

The second lesson — the canary in the coal mine — is that because of global warming the frequency of these extreme weather events is only going to increase. Thus the one in 100 year high rainfall event will become far more common, with highest-ever totals being exceeded more and more often in the future.

The third lesson is that there needs to be better preparation for these events by civil society. The responsibility in New Zealand falls on local bodies through the Civil Defence and Emergency Management Act (CDEM). It’s local government that is responsible for district plans and granting developers the permission to build. Firstly should major towns be located on river floodplains? This is where there is pressure from developers. A solution is to build higher and higher flood levees but should the cost be borne by the community? Perhaps the full costs should be placed on the developer. Another option is to ban development in flood-prone areas.

However New Zealand is the lucky country in regard to the fourth lesson. We have an Earthquake Commission that covers citizens for flood damage, which Australia does not have. But insurance should be compulsory for all dwellings, to share the cost of these disasters between all citizens.

Global warming is here, now — and not a phenomenon for future generations to deal with. Thus we must embark on a course of emissions reductions targets as soon as possible, to claw back rapidly rising greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere. If we do not act now the severity of such floods, and the subsequent loss of life and property — let alone the effect on the economy — will increase dramatically. There is no time like the present to invest in our future wellbeing.

Institutional lemmings

I was struck by a passage in Noam Chomsky’s conversational remarks on climate change in the video clip Gareth recently posted. Commenting on the campaign waged by powerful business lobbies to convince the public that global warming is a liberal hoax, he pictures the people responsible as trapped by their functions in the institutions they work for. He put it rather starkly:

“Those same CEOs and managers who are trying to convince the public that it’s a liberal hoax know perfectly well that it’s extremely dangerous. They have the same beliefs that you and I have. They’re caught in a kind of institutional contradiction. As leaders of major corporations, they have an institutional role – that is, to maximise short-term profit. If they don’t do that they’re out and someone else is in who does do it, so institutionally speaking it’s not a choice that’s going to happen in the major institutions.

“So they may know that they’re mortgaging the future of their grandchildren and in fact maybe everything they own will be destroyed, but they’re caught in a trap of institutional structure. That’s what happens in market systems.

“The financial crisis is a small example of the same thing. You may know that what you are doing is carrying systemic risk but you can’t calculate that into your transactions or you’re not fulfilling your role and someone else replaces you…and that’s a very serious problem. It means we’re marching over the cliff and doing it for institutional reasons that are pretty hard to dismantle.”

Chomsky was speaking with a degree of informality, and I don’t want to put his statement under close scrutiny. Nor am I necessarily expressing agreement with all that he says. But I thought the general drift of his remarks had point. Something happens in the very structure of society to prevent a rational response to the threat of climate change.

I often find myself wondering what is going on in the minds of people whom one would normally expect to be respectful of major scientific endeavour but who when it comes to climate change seem to be able to relegate that respect, if not to the point of denial at least to the level of a secondary consideration, which in reality it clearly isn’t.

I’ll leave the corporate field to Chomsky and take a look at what the New Zealand government has to say about the 2050 emissions target which they propose gazetting and for which they are inviting public submissions by the end of this month. The Minister, Nick Smith, has put out a position paper in support of the target of a 50 per cent reduction from the 1990 level by 2050. The paper acknowledges and accepts the basic science and the impacts predicted by the IPCC 2007 report. There’s no suggestion of denial. But nor is there any acknowledgement of how serious those future impacts will be for humanity. Nor any hint of the possibility that on such a question as sea level rise this century the IPCC estimate appears likely to be exceeded, perhaps considerably. The language outlining the science is flat. The paper moves to indicate that New Zealand has a unique emissions profile by comparison with other developed countries, mentioning the high level of emissions from livestock farming, the lower than normal level of CO2 emissions from electricity generation, and the significant impact of forestry planting and harvesting on our emissions level. From there the emphasis is on where we fit into the international picture, not at all on the imperative posed by climate change. This sort of statement:

“The world is changing and other countries are recognising the reality of a carbon-constrained future. It is in New Zealand’s long-term interests to begin taking steps towards a low-carbon future.”

Emphasis is given to how it is more challenging for us than for most other developed countries to reach a given level of emissions reduction because of our unique emissions profile. Satisfaction is expressed that a 50 per cent reduction by 2050 is nevertheless in line with what most other developed countries are aiming for and the conclusion drawn that we are certainly doing our fair share.

By now the statement has left far behind any consideration of what the science demands, not only of us but of the community of nations. It has become an exercise in positioning ourselves, doing enough to satisfy our international partners but nothing that might seriously disturb the economy we are used to.

“Setting a target is a balance between achieving the reductions in greenhouse gases we want and the impact on the economy and our lifestyle. Achieving the 2050 emissions reduction target could mean higher costs for consumers and businesses as we transition to a low-carbon economy. However, a less ambitious target would undermine New Zealand’s clean, green environmental reputation. The proposed 2050 emissions reduction target balances these demands and reflects a fair contribution by New Zealand to the international effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

Nick Smith and Tim Groser must be aware of the science and of the seriousness of the danger ahead if emissions are not far more drastically reduced than the international scenario they relate us to. No one will argue that the economy and lifestyle don’t matter. But how can they somehow ‘balance’ the need for action to reduce emissions? This looks very like what Chomsky identifies as institutional contradiction. It’s not as gross as short-term corporate profit, or as the anti-science denial seemingly rampant in the US Republican party, but in a lesser way does it not reflect the same phenomenon? The role of the politician is restricted by the need to keep happy those vested interests resistant to changes to the economy and those citizens judged incapable of facing reality. Protecting future generations, let alone those poorer populations already being impacted by climate change, is not part of the role and is not rewarded. Chomsky acknowledges those institutional reasons are hard to dismantle, but meanwhile, as he says, we’re marching over a cliff. Reason enough for the dismantling to begin.

Something for the weekend: poles, podcasts and Chomsky

Something for everyone this weekend: a few podcasts to grab, ice news from both ends of the planet, interesting reading, and a great interview with Noam Chomsky. Audio first: Radio NZ National’s Bryan Crump interviewed Prof Jean Palutikof, Director of the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility at Griffith University in Queensland at the beginning of the week. It’s a wide-ranging discussion: Palutikof is an engaging speaker and frank about the dangers we confront. Grab the podcast now, because it’ll disappear from the RNZ site on Monday.

Something for everyone this weekend: a few podcasts to grab, ice news from both ends of the planet, interesting reading, and a great interview with Noam Chomsky. Audio first: Radio NZ National’s Bryan Crump interviewed Prof Jean Palutikof, Director of the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility at Griffith University in Queensland at the beginning of the week. It’s a wide-ranging discussion: Palutikof is an engaging speaker and frank about the dangers we confront. Grab the podcast now, because it’ll disappear from the RNZ site on Monday.

Continue reading “Something for the weekend: poles, podcasts and Chomsky”