The first comprehensive scientific review of our understanding of Antarctic climate and the way that it’s changing was published in the UK earlier this week [ScienceDaily]. The Antarctic Climate Change and the Environment report (a free download), prepared by the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR), points to ten key findings [PDF]:

The first comprehensive scientific review of our understanding of Antarctic climate and the way that it’s changing was published in the UK earlier this week [ScienceDaily]. The Antarctic Climate Change and the Environment report (a free download), prepared by the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR), points to ten key findings [PDF]:

- For the last 30 years, the ozone hole has shielded the bulk of the Antarctic from the effects of “global warming”

- The Southern Ocean is warming – the ecosystem will change

- There has been a rapid expansion of plant communities across the Antarctic Peninsula

- Parts of the Antarctic are losing ice at a rapid rate

- Sea ice has increased in extent over the last 30 years as a result of the ozone hole

- Paleoclimate studies in Antarctica show that the current shock to global climate is unusual

- Marine ecosystem components, such as krill and penguins, linked to the sea ice show a clear response to climate change

- Assuming a doubling of greenhouse gas concentrations over the next century, Antarctica is expected to warm by around 3ºC

- West Antarctica could make a major contribution to sea level rise over the next century

- Improved representation of polar processes is needed in models to produce better predictions

The full report weighs in at 526 pages [20MB PDF] and is a superb overview of the state of our knowledge. It’s not an easy read, but in the manner of the IPCC reports is comprehensive and carefully referenced, with lots of illustrations of what’s going on. Recommended. The BBC has good coverage of the sea level implications, Stuff picks up on the “greening” aspect, and the Guardian notes that warming will accelerate as the ozone hole heals.

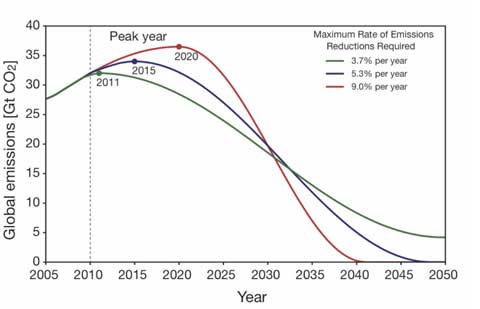

The Copenhagen climate conference (

The Copenhagen climate conference (

The last time CO2 hit a sustained level of 400 ppm 15-20 million years ago global average temperatures were 3 – 6ºC warmer than now, and sea level was 25 to 40 m higher, according to

The last time CO2 hit a sustained level of 400 ppm 15-20 million years ago global average temperatures were 3 – 6ºC warmer than now, and sea level was 25 to 40 m higher, according to  Sea level will rise by more than a metre by 2100 according to the authors of the third chapter in the World Wide Fund for Nature’s new Arctic report,

Sea level will rise by more than a metre by 2100 according to the authors of the third chapter in the World Wide Fund for Nature’s new Arctic report,