Hot Topic has frequently given credence and drawn attention to Oxfam’s reports on how climate change is already seriously affecting populations in developing countries. (Some examples here and here and here.) It is therefore pleasing to see that a complaint to the UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) regarding an Oxfam poster has been rejected.

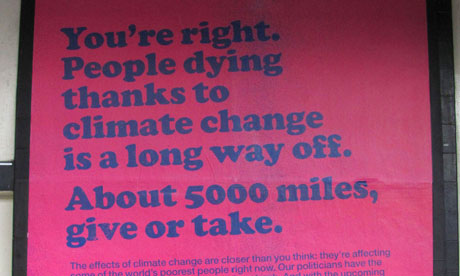

The poster stated “People dying thanks to climate change is a long way off. About 5000 miles, give or take… Our politicians have the power to help get a climate deal back on track… Let’s sort it here and now.” Four people challenged the poster on the grounds that it was misleading and could not be substantiated. They did not believe it had been proven that people were dying as a result of climate change.

Asked by the Authority to respond, Oxfam said research had been published by reputable organisations including the World Health Organisation (WHO), the Institute of Medicine (the health arm of the US National Academy of Sciences), the Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission that showed people had died, and were currently dying, as a result of climate change. In particular, they cited three WHO publications which they considered backed up Oxfam’s claim. In addition, they said Oxfam’s own experiences bore out ways in which climate change, manifesting as trends towards increased temperatures, disrupted seasons, droughts and intense rainfall events created additional health hazards for vulnerable populations in the countries in which Oxfam worked.

The ASA in its adjudication referred first to the IPCC and other national and international bodies with expertise in climate science and concluded there was a robust consensus amongst them that there was extremely strong evidence for human induced climate change. The ASA noted that the part of Oxfam’s claim that stated “Our politicians have the power to help get a climate deal back on track … let’s sort it here and now” made a link between human action and climate change.

The ASA then turned to the question of whether there was a similar consensus that people were now dying as a result of climate change. They referred to several WHO reports. One was the 2009 publication Global Health Risks – Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks [PDF], which stated “Climate change was estimated to be already responsible for 3% of diarrhoea, 3% of malaria and 3.8% of dengue fever deaths worldwide in 2004. Total attributable mortality was about 0.2% of deaths in 2004; of these, 85% were child deaths”.

Satisfied that there was a consensus that deaths were now being caused by climate change, the ASA finally noted that Oxfam’s claim was reasonably restrained in that it stated deaths were occurring at the present time as a result of climate change but that it did not claim specific numbers of deaths were attributable and it did not speculate about future numbers of deaths.

The ad was judged not misleading. (The full text of the adjudication is on the ASA’s website.)

Oxfam is not pushing the envelope in its reports and claims of what climate change is already meaning for some populations in the developing world. It is well within the limits of the science. It may be a shock to some to realise that, and there are always those ready to discount it as alarmism aimed at increasing the organisation’s income. But it is no more of an exaggeration to say that people are already dying as a result of climate change, than to say that people die as a result of tobacco smoking. Those of us who have lived long enough may remember how long and hard the latter conclusion was resisted by the counter-claims of the industry and the widespread public unwillingness to face the reality. Fifty years ago when as a young man I took up tobacco smoking for a period of some years I assumed the medical warnings which were beginning to be sounded were bound to be overstated. The very normalcy of smoking made it easy not to take them seriously. And there were plenty of assurances abroad that there was little to be concerned about. I shudder now to think how easily we blinded ourselves.

The analogies with the far greater issue of climate change are all too apparent. The efforts of Oxfam and others to puncture our complacency are justified and necessary. May they not have to wait decades to succeed.

[Wilco]