The global climate is changing. The impacts on human society are likely to be very serious. We would be foolish indeed not to plan ahead for coping strategies. Michael Mastrandrea and the late Stephen Schneider have produced a small book setting out what we can best do to be ready for what is in store. Preparing for Climate Change is one of the Boston Review Books, a series of “accessible, short books that take ideas seriously”.

It’s a thoughtful, well-organised piece of writing which leads the reader by steps through what is needed to prepare for what climate change will bring. The first step is to understand that global warming is for real. It’s under way and it is largely due to anthropogenic forces. However predicting its future course is difficult because of two things we don’t know — how much more greenhouse gases humans will emit and exactly how the natural climate system will respond to those emissions. The temperature rises we face will depend on the level of emissions, and the range of projections for the year 2100 that the IPCC has estimated on the basis of six different scenarios is very wide, from as low as 1.1 degrees to as much as 6.4 degrees. The latter could be catastrophic. The former looks increasingly likely to be well surpassed. But even a comparatively low level of temperature rise would bring damaging changes for some communities and ecosystems. Indeed the 0.75 degree increase of the past century is already showing some worrying impacts.

The authors then outline the key vulnerabilities that need to be taken into consideration. They include glacier loss, melting ice sheets, sea level rise, higher infectious disease transmission, increases in the severity of extreme events, large drops in farming productivity especially in hotter areas, the loss of cultural diversity as people have to leave their historical communities, and an escalating rate of species extinction. Many of these can already be witnessed in their early stages, and the book provides examples from various parts of the globe. Additionally, however, there is the possibility of “surprises”, fast non-linear climate responses which may occur when environmental thresholds are crossed. Some can be imagined, such as a collapse of the North Atlantic ocean currents or the deglaciation of Greenland or the West Antarctic ice sheets. But because of the enormous complexities of the climate system there is also the possibility of unforeseeable surprises.

In the face of inherent uncertainty we have to proceed by risk assessment and risk management as we make our policy decisions. Risk assessment is primarily a scientific enterprise. Risk management – deciding which risks to tolerate and which to try to avoid – is a political matter where values enter into play. However the relationship between the two is complicated by the uncertainties of the scientific predictions. These uncertainties will be reduced as research proceeds under normal scientific practice, but answers of some kind are needed well before this time. There are policy decisions to be taken before there is a clear consensus on all the important scientific conclusions. The authors discuss type I and type II errors at this point. A type I error will be committed if we act to mitigate climate change and discover that our worries prove exaggerated and anthropogenic greenhouse-gas emissions cause little dangerous change. A type II error will be committed if we delay action until greater certainty is established and in the process allow serious damage to occur. We have a choice as to which type of error it is better to avoid.

What actions does sensible risk management indicate? We know that reducing emissions will reduce the level of temperature increase that would otherwise occur, but we also know that further climate change will happen no matter how quickly we are able to reduce emissions. We must therefore both try to limit future emissions and at the same time adapt to what we cannot escape. Mitigation and adaptation must be complementary and concurrent.

The authors recognise some adaptation as autonomous; it is reactive in response to the impacts of climate change. However they consider it vital to also plan adaptation. Planned adaptation may be reactive, but the book lays stress on planning which is anticipatory, as for example in the protection of coastal infrastructure. Anticipatory adaptation is an investment, but one which may not be able to be afforded by poorer developing countries. The book notes that the Copenhagen Accord recognised this and included a commitment to provide resources for adaptation investment in such countries.

But adaptation measures can only go so far, and mitigation must be seriously pursued in tandem. Although the book focuses a good deal of its attention on how we can plan for adaptation it is clear that there must be a mix with mitigation measures adequate to keep adaptation manageable. The third more drastic response to climate change of geoengineering is briefly considered, and described as desperate: understandable, but not what the situation demands as a first response.

Whatever mix of mitigation and adaptation we adopt the authors are firm that equity issues must be part of planning. The needs of vulnerable and marginalised groups must be a prominent consideration when forming climate policy.

The question of vulnerability is faced in their final chapter. They see vulnerability assessment as an essential tool to inform the development of climate change policies. Exposure to stress, sensitivity to the exposure, and adaptive capacity are the three components which need to be considered. Mitigation reduces vulnerability by reducing exposure. Adaptation reduces vulnerability by turning adaptive potential into adaptive capacity. New Orleans before Katrina had quite high adaptive potential, but it was not realised and adaptive capacity was therefore low. Vulnerability assessment is a complex task and they argue for a close relationship between those on the ground in specific regions (bottom-up) and the climate-impact assessments of scientists (top-down). Again, questions of justice are high in their priorities. We must be sure that marginalised countries and groups are not ignored as we tackle the potentially dangerous, irreversible climate events ahead.

For those familiar with the subject the ground the book covers is probably not new. But the writers are authoritative and their treatment is well organised and logically ordered. It is also informed by a strong sense of humanity. Their book is an excellent short statement for the general reader and a useful summary analysis for those who appreciate a reminder of how the various elements fit together. Don’t be misled by the moderate tone or the acknowledgement of the uncertainty which must attend predictions of future change. The authors know they are writing of an urgent and pressing need to prepare in advance if we are to avoid the worst consequences of climate change.

[Help Hot Topic to meet its running costs by buying via Fishpond (NZ), Amazon.com, or Book Depository (UK, with free shipping worldwide).]

Like this:

Like Loading...

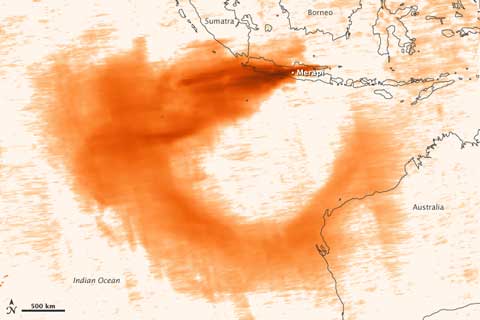

Back in April, when Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland was erupting and causing much disruption to air travel in Europe and the North Atlantic, there was some concern that the volcano’s ash and aerosols could cause global cooling. As I said at the time, there was little chance of that happening because volcanoes need to be near the equator to cause global cooling events. However, we now we have an eruption in Indonesia that has the potential to cause a noticeable global cooling. Merapi is Indonesia’s most active volcano, and the eruptive sequence which began at the end of October has already killed at least 153 people and emitted a considerable amount of sulfate aerosols as this NASA Earth Observatory image shows:

Back in April, when Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland was erupting and causing much disruption to air travel in Europe and the North Atlantic, there was some concern that the volcano’s ash and aerosols could cause global cooling. As I said at the time, there was little chance of that happening because volcanoes need to be near the equator to cause global cooling events. However, we now we have an eruption in Indonesia that has the potential to cause a noticeable global cooling. Merapi is Indonesia’s most active volcano, and the eruptive sequence which began at the end of October has already killed at least 153 people and emitted a considerable amount of sulfate aerosols as this NASA Earth Observatory image shows: